This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Tuesday, June 30th, 1989 became a landmark date in Sudanese political memory. It was the day the National Islamic Front overthrew a pluralist parliamentarian regime, thus vitally questioning the extent to which that movement believed in democracy. Contrary to what was commonly presumed, the Front was a recognised political entity. It campaigned in its capacity as such during the 1968 elections and got in third, subsequently forming the main opposition. It also formed a government coalition with both the Umma Party and the Democratic Unionist Party.

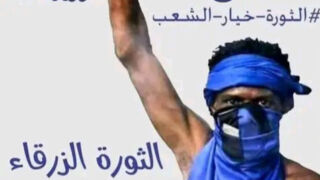

June 30th, 2019 was also the day a powerful popular unrest chose to take down the “Salvation” regime and its president, Omar al-Bashir. People went out in mass protests to reassert their dual objective: submerging the memory of that Salvation coup date with their street power and dynamism, while challenging the Transitional Military Council, tipping the political power balance in favour of the civil stream. For last year’s June 30th protest took place after 27 days of bloody dispersal of the sit-in, which had endured for 58 days (10 days longer than Rab’aa al-‘Adawiya sit-in in Egypt), amidst a full-blown internet freeze and speedy efforts by the Military Council to communicate with alternate political bodies – be they chieftains, local administrators, or certain personas linked with the fallen Salvation regime. The achievement realised by the popular unrest then took shape as a reinstatement of the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC), which the Military Council had previously disqualified following the dispersal of the sit-in, as sole negotiator of the transitional phase arrangements.

The power and dynamism of the popular unrest was neither employed to confront the military troops alone nor was it a mere blank cheque; rather, it was channelled to confront the government of Dr. Abdallah Hamdok, whom the FFC had instated as prime minister. On June 30th, 2020, the streets were divided into yet another million people march, despite the coronavirus pandemic; this once, however, it took to the streets under the banner of “readjusting the course”, in clear reference to their disappointment with the sluggish rhythm of things and inability to realise any significant achievement. Things were repeated with the demonstrations of “reckoning”, which commemorated one year of the Transitional Constitutional Charter, signed on August 17th.

Although Sudan had lived through two popular unrests before, which managed to overthrow two military regimes in 1964 and 1985, the most recent was characterised by three major phenomena: it took off from the peripheries before reaching the capital; women and youth were markedly present; and the streets remained relevant to the political landscape and active within it, rather than withdrawing once change had been realised, which was customary before, whereby governance would be left up to politicians alone.

June 30th, 2019 was the day a powerful popular unrest chose to take down the “Salvation” regime and its president, Omar al-Bashir. People went out in mass protests to reassert their dual objective: submerging the memory of that “Salvation” coup date, while challenging the Transitional Military Council, tipping the political power balance in favour of the civil stream.

As it took off from the periphery, the popular unrest indicated this once that the centre was no longer the only player in the political field, a controversy that had factored into the unrest, culminating in insurgent movements in Darfur, Blue Nile, and South Kordofan states. The continued disregard and impoverishment of the periphery was yet another factor that played into the unrest; for instance, the demonstrations in Atbara city, Northern Sudan, had taken off because it was the first city to try lifting subsidies on bread in December 2018. Citizens were struck by a spike in bread prices – not one bag of rice in the city was left subsidised back then. For, throughout the rule of different regimes, meeting the needs of the capital city was customary, whereby the largest subsidies possible would be bestowed upon it to appease its residents, as they were the ones who geared up for protests and subsequently changed governments.

Women and youth played a growing role throughout the current unrest, connoting as such they were the two most affected groups who suffered the policies and practices of the previous regime. It is ironic, however, that those very young people grew up and acquired their knowledge and worldview throughout the 30-year-long Salvation period. Even some party leadership and organisations at the forefront of this popular resistance were only ten-year olds when the “Salvation” regime took over.

Throughout that period, those youths lived through many a rough experience during their compulsory national service, sometimes sent off to wars, and, at others, resulting in tragedies like in the one in Eilafoun military camp, east of Khartoum, where 74 student conscripts were killed and 55 had drowned as they tried to escape. Their mass grave has been recently found. (The killings took place in 1998, just before Eid al-Adha. The camp was situated at the outskirts of Eilafoun city, some 40 km southeast of the capital overlooking the Blue Nile. Things started with the conscripts asking for permission to take leave to celebrate Eid al-Adha, which the commanders refused…).

Moreover, the Salvation regime resorted to a method of prioritising its partisans and supporters in job opportunities, facilitating procedures for their joining commercial or investment activities. As such, regardless of whether they belonged to the opposition or not, others were met with a locked door, that is, unless their name showed up on one of those politically preapproved lists, fabricated by the regime and its numerous institutions amidst youth, workers, and businessmen circles.

Dwindling options, especially immigration and job opportunities in neighbouring countries, particularly the Gulf, exacerbated the situation. In previous periods, even during the early Salvation era, thousands of people fired from their jobs would chance upon immigration to Europe or North America; their dismissal from military service and the torture they suffered in the first place would constitute the grounds upon which they managed to secure legal status in their respective exiles; whereas thousands of others headed to the Gulf, to regional and international organisations, or some other neighbouring countries, either as workers or investors.

The Salvation regime adopted many a hostile and controversial foreign policy, which unfolded in a large number of countries freezing, if not cutting off, their relations with Sudan. Things peaked by listing Sudan as a State Sponsor of Terrorism in 1993, with reprecussions the country suffers from still, including diminished immigration and job opportunities available to youth. Unable to leave, they were cornered into confronting their own domestic reality and working on transforming it, particularly since such reality was constantly deteriorating as political and economic reforms reached a deadlock.

The dynamism of the popular unrest channelled to confront the government of Hamdok, whom the FFC had instated as prime minister. On June 30th, 2020, the streets were divided into yet another million people march, under the banner of “readjusting the course”, in clear reference to their disappointment with the sluggish rhythm and inability to realise any significant achievement.

The desire for change intersected with a fertile ground for change, topped by a deteriorating economic state, as South Sudan separated into an independent state in 2011, transporting three quarters of all known oil reserves along with it. The country was headed for a depreciation of the Sudanese pound by 60 percent, a voyage that has been rapidly accelerating since.

Women, on the other hand, suffered under the Salvation regime in two main facets: the first being the “Public Order Law”, which persecuted women all the way to their clothing, subsequently leading to the formation of anti-sexist groups, such as the “No to Oppression against Women Initiative”. Moreover, economic policies and routine security measures aggravated impoverishment, with women paying its highest price with more bankrupt households and absent husbands, fathers, and brothers – either due to state and tribal violence, or due to the collapsed model of rural economy. As such, women were burdened with further responsibility over their households, leading to a proliferation of menial jobs, with many becoming tea and coffee ladies, among other jobs.

On the other hand, traditional political powers could not capitalise on the state of crisis the Salvation regime suffered in order to challenge the regime. Such weakness manifested in the negligible popular response, which ignored the conventional powers’ calls for protests at the beginning of January 2018 – that is, when the government began to partially lift its subsidies on certain goods.

Triumph and demands

When the Sudanese Professional Association emerged, towards the end of that same year, it was the complete opposite: its repeated calls for protesting were met with growing response. People would gather at 1pm exactly, as the association flyers specified, one of the marching ladies or young women would ululate, and the demonstration would punctually commence, at the set time. The Association was thus heartened to move things up a notch, turning its chants away from lifestyle demands –related to low salaries and rising living costs– into political ones, calling for the departure of the Salvation regime. The Protests culminated into the Freedom and Change Charter, signed on January 1st, 2019 by various political parties, professional associations, and civil society organisations.

Lebanon: A Special Type of Rent

13-12-2020

The veracity and backing the Sudanese Professional Association enjoyed mainly pertained to their split with the traditional establishment of political powers, especially partisan powers, previously tried one way or another. Likewise, the popularity that Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok enjoyed could be similarly explained: he did not hail from within the conventional club of political leaderships, but rather from the peripheries of South Kordofan State (as opposed to the Nile centre, wherefrom the political leadership that had ruled Sudan would often come), and he worked in a number of international establishments for many years which, in the Sudanese imaginary, are considerably respected and esteemed – as they are deemed capable of creating solutions.

The desire for change that many growing powers shared intersected with a fertile ground for change, topped by a deteriorating economic state, which received a semi-fatal blow as South Sudan separated into an independent state in 2011, transporting three quarters of all known oil reserves along with it. At the eve of its separation, deprived of financial revenues, the country was headed for a depreciation of the Sudanese pound by 60 percent, a voyage that has been rapidly accelerating since.

With such essential change in the economic landscape coincided another, equally important, change inside the political scene of the Salvation regime. Two years after the South separated, al-Bashir removed two main people from his cabinet: his first vice president, Osman Mohammed Taha, and his other vice president, Dr. Nafe’a Ali Nafe’a. As such, he practically terminated the involvement of the Islamic Movement in governance, whose symbolic presence he maintained, an accessory to be summoned to confirm the regime’s legitimacy and legality, at least before its political base. However, on both actual and practical levels, al-Bashir became the one and only centre of authority and point of reference, which gradually pushed him to rely on his own family and entourage.

Women, on the other hand, suffered under the Salvation regime in two main facets: the first being the “Public Order Law”, which persecuted women all the way to their clothing, subsequently leading to the formation of anti-sexist groups, such as the “No to Oppression against Women Initiative”.

With deteriorating economic crises; a declined ruling political base; a reform impasse reached following the international siege imposed on Sudan; the ICJ’s indictment of al-Bashir; his insistence on holding onto presidency, nominating himself time and again as if presidency was guaranteed as his; the regime had started to enter, bit by bit, a stage of failed rule. Bakri Hassan Saleh’s government, the first government to separate prime ministership from the presidency of the republic, thus lived a period of a mere 18 months, followed by Motazz Moussa’s government, which lasted less than five months, and, lastly, Mohamed Tahir Ayala’s government, which was wiped out by the popular uprising, eight weeks into its formation. Incapacity to rule worsened the liquidity crisis, which the regime also failed to face.

Anxious Arrangements

Such incapacity is what pushed the security establishment to side with popular unrest and remove al-Bashir. A chapter of anxious arrangements would thus begin, transpiring throughout the transitional period, ultimately projecting active power balances and complexities onto the political scene. The security establishment includes the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces. The latter was key in confronting insurgent movements, especially in Darfur, using those same guerrilla war tactics, and achieved considerable success. Al-Bashir merged them with the Armed Forces and made them his, guaranteeing his future rule as such. The security establishment also comprises security and intelligence services and their striking power. On the other end we find the Freedom and Change Forces, amidst which is the Professional Association and some civil society organisations, alongside the conventional political parties. The arrangement unfolded into a provisional period that would last three years and three months, and a Sovereignty Council whose rule was shared between the military and civil streams with a civil majority, and a cabinet the FFC would nominate, given every executive authority, while the military stream would oversee both the ministry of defence and interior. Dr. Abdalla Hamdok, former deputy executive secretary of the UNCEA, was thus chosen to head the government.

Nonetheless, one year following the formation of the government, a third of the transitional period having passed with no tangible accomplishments to show for, the popular movement seems to be faced with an intersection. Economic afflictions have deteriorated into a stage of deep crisis and made worse by lack of political and economic visions or plans that would guide the government. A state of exhaustion has thus been created, saturated with a climate of mistrust in any possibility to achieve any reliable results. For, even if Sudan’s name were to be removed from the US State Sponsors of Terrorism list, and even if a peace treaty were to be concluded with some of the insurgent movements, no real conviction exists that two such steps, though significant, could successfully upturn the state of mounting confusion and pessimism. The disappearance of the hashtag “Thank you, Hamdok”, replaced by journal articles and political statements critiquing Hamdok, vouches for such a state.

The previously clear divides between the military and civil components in the provisional arrangements increased and deepened among the FFC, which politically foster the government and the entire transitional period. Divisions amidst the Sudanese Professional Association, with some of its members quitting the FFC, are considered some of the most important signs of such fragmentation. In parallel, the Umma Party, the Sudanese Communist Party, and the Sudanese Congress Party, continuously critique the government, each from its own viewpoint.

A chapter of anxious arrangements began, transpiring throughout the transitional period, ultimately projecting active power balances and complexities onto the political scene. The security establishment includes the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces. The latter was key in confronting insurgent movements, especially in Darfur.

Sensing the waning power and fragmentation of the FFC, the government began adopting a single-handed approach in its decisions, bypassing FFC and its components. It did so as it appointed some Civilian Walis, whose names Hamdok declared, and as it approved the amended budget despite warning calls the FFC financial committee shared and, finally, as it proposed a trade unions bill conflicting with FFC’s proposition.

Two aspects come up through the government’s last two decisions: that it had resorted to the IMF formula, which stipulates lifting subsidies on fuel, cooking gas, electricity, and bread – a condition the donors presumably placed, who made it very clear that they had no intention to provide their economic support to end up wasted on subsidising such commodities. In fact, the government went one step further in its attempts to control the economic situation, even at the expense of the producers. For instance, it obligated farmers to sell their yield of wheat to the agricultural bank for a price of 3,500 Sudanese pounds per tonne at a time the market prices were 5,000 Sudanese pounds per tonne.

The other aspect that reveals the government’s desire for control is embodied in the unions bill it proposed. There, it maintained the establishment union –which comprised professionals, administrators, and technicians, of the former era– as the elected one, thereby eradicating unique unionist identities. Eventually, one of the professors ended up president of the Sudanese Workers Trade Union Federation. Many political powers then negotiated a draft that would re-concentrate on group and trade unions. As such, they attempted to create a tangible hint of a change within the unionist landscape, raising the pivotal role the Professional Association played during the popular unrest and in taking down the Salvation regime. Thus, those political powers were rendered in direct opposition with the draft bill the government proposed.

Such position reflects the main dilemma this transitional period features. The idea behind extending this period beyond three years aimed to dismantle the “empowerment” legacy, which was engaged by the overthrown regime, as well as paving the way for an agenda of democratic transition, starting with holding pluralist elections in a climate of freedom. In short, the FFC Charter called for laying out the foundations for state-building, but disregarded the fact that such state-building would require more than an agreement over the bare minimum – namely, animosity towards the former regime. Things get further complicated with no viable leadership or political willpower to create a detailed applicable agenda. Ultimately, the FFC is an alliance between quarrelling political bodies, rather than a united organisation.

As such, as the FFC divisions and fragmentation expand, political needs are bound to compel a form of a rearrangement, further rapprochement, and better coordination between the civil government and the military stream. The challenge lying before the FFC would thus be figuring out how to handle such a situation on the one hand, and how to pressure Hamdok’s government to change the policies it had begun implementing on the other, which are essentially akin to Salvation policies. Most importantly, the FFC would have to stabilise matters for the Walis, most of whom it helped appoint, a challenge to FFC’s political capacity, notwithstanding its command of a popular base that reaches beyond the previously proliferating regional and tribal divisions.

Two main factors that could play a role in somehow directing the path of future events remain, then. The first would be the international delegation to reach Sudan at the beginning of 2021, to help finalise arrangements of the transitional period. Despite whatever help such delegation could offer, however, particularly in technical aspects, such as carrying out a census or an election, or in peace-keeping programmes, such as the reintegration of fighters, its effect would be extremely limited in pushing the political powers towards the compromises required to reach a state of national accord – an essential condition to successfully pass this period.

Until now, the “resistance committees” have generally represented a state of a continued revolutionary climate on the street level and have become a major factor in the political scene.

The second factor is embodied in the street climate and the extent to which its dynamism could continue to pressure both government and political powers to better handle and achieve some of the objectives of the popular movement, and to transition into a stage of real structural change of the 60-year old elite establishment that has been dominating the country. One of the aspects that requires special attention and monitoring is the work of the Civil Walis. Despite the hurdles, and despite objections to eight out of the eighteen appointed Walis, those appointments demonstrated people’s mixed viewpoints through the various FFC podiums. The challenge lies within the way the government and FFC managed to traverse this stage and establish a principle by which authority would spring from within, that is, from the popular base. It also lies in the extent to which the political choices of the FFC could succeed in facing regional and tribal objections. It would mean a quantum leap in its practices, whereby its authority would spring from its supportive masses.

Until now, the “resistance committees” have generally represented a state of a continued revolutionary climate on the street level and have become a major factor in the political scene. However, they require a certain amount of control; likewise, their activities should cease to clash with those of the State apparatuses. And, most importantly, how these committees’ activities could be organised and channelled into the political mainstream must be examined. Similarly, the elite club must be examined under the microscope of mass accountability, having dominated political life in Sudan, single-handedly, and for far too long.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 01/10/2020