This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

From February 22, 2019, and for more than a year, the popular movement mobilized crowds in the big cities of Algeria until it was interrupted by the Covid-19 pandemic. It seems fitting, now, to take the time to examine and discuss what had happened to us and within us during those extraordinary days, to discover what has remained from the experience we believe we have forgotten, to retrace it in our imagination, in our ways of being, creating and hoping, and to convince ourselves that it wasn’t all in vain.

Already there have been a few collective books and a few films with varying ratings, and surely there will be other productions as well. However, something liberating has happened inside our minds, as if it had suddenly become possible for us to become actors in the making of our destinies, after decades spent in silence.

Perhaps our reminiscences will be tainted with a touch of melancholy, since the atmosphere in the current phase is one of settling of scores, arrests of dozens of the movement’s leaders, ideological debates and trivial divisions. However, it is still necessary to look back so as to be able to look forward to a brighter future and avoid despair.

Preliminaries of patriotism

We had every good reason to revolt, as our humiliation was embodied in the image of the corrupt old president, clinging to power like a louse, with his entourage of contemptuous people who share power amongst themselves in closed circles of private interests. They had put Algeria under their thumb, shamelessly pumping out its wealth and silenced all free expression, criticism, and any ambition for those who were not members in this exclusive club. In fact, we no longer understand exactly who constitutes this club; is it the state, the regime, the security apparatus, or something else that had emerged from all that in the form of a unique mafia? These feelings were exacerbated by the so-called “Case of the 700 kilos of cocaine”, discovered at the port of Oran, in which individuals close to power were involved.

The “blessed day” did not arrive all at once like an unexpected thunderstorm in a clear sky. There were evident signs of its approaching, discerned by those who wanted to see, and mediated by the new media. All those who belonged to the opposition appeared on Berbère Télévision or Al-Magharibia TV, believing that this pragmatic approach was more useful in making their voices heard on satellite media, rather than continuing to be banned from the ill-reputed state TV, referred to as “the channel of shame”, as opposed to Al-Magharibia TV, which is an Islamist channel based in London and revered by a part of the exasperated population as “the channel of the people.”

On social media, things were no different, and out popped the names known to all. One of the rising influencers was a young man named “Amir DZ” (1) who, while he lived abroad, succeeded in turning his account into a credible reference for a large part of the population by criticizing the decadence of those in power and their children, revealing their scandalous involvement in corruption and the stretch of their tentacles which reach every corner.

Some of Amir DZ’s followers were arrested before February 22, 2019, including a few celebrity TV stars who were shown on local TV channels, bewildered and in handcuffs. This incident allowed testing the effectiveness of the cybercrime brigade created a few years earlier, which began to identify all the somewhat naive individuals who sought online fame, having believed that they had found a space of freedom to say it all on their social media pages. Unfortunately, what the following events would prove is that the cybercrime unit had indeed been serious and ardent in its work.

From the neighboring Morocco, whose demonstrations we had followed closely, the Algerian uprising borrowed the word “Hirak” (which is a variation on “movement” in Arabic). The word would come to be debated as it didn’t sit well with the orthodox puritans of the language of Al-Moutanabbi. However, the word had a nice ring to it, and it carried the idea of movement and broke from the sanctified linguistic codes that had been in action until then. Hence, the term was adopted in Algeria, appropriated from the “Hirak al-Rif” (the rural movement in Morocco) to “al-Hirak al-Chaabi” (the popular movement in Algeria), perhaps creating grounds for a “Maghreb of the people”.

With the announcement of a fifth term for this pathetic president, the unbearable became more pervasive, and even Algerian humor no longer managed to conceal the deep humiliation generated by this comedy of power which still insisted on making us play the role of the obedient extras in its show, while it uses this absent body for its ends.

“La Casa d´El Mouradia” released in 2018 by the Algerian football club, USMA, became a popular success after its interpretation by the collective “Ouled el Bahdja”. During the Hirak, the song was endorsed by rival football clubs, which heralded a paradigm shift.

In the beginning, there was a large march on February 16, 2019 in Kherrata, a historic city and the symbolic site of the major demonstrations of May 8, 1945 (rallies that celebrated victory over Nazism and demanded the independence of Algeria). At the time, the city witnessed a massacre in which tens of thousands of Algerians were killed by the settlers and the police, just because they believed that they had earned the right to be free. In another image, on February 19, in Khenchela, the demonstrators forced the municipality to remove the president’s portrait from its façade, showing an absolute rejection of the cult of personality which we have grown used to during the twenty years of his reign.

2019-2020: Algerian Power versus the Hirak

10-02-2021

And more than this, numerous YouTube videos were posted of football fans, or “Ultras”, in the stadiums, singing at the top of their lungs the anthems of their clubs and uncompromisingly shouting out their political slogans in the beautiful popular language. They use this language to occupy the channels of free expression which are impossible to ban, infiltrating, by their huge numbers, the united and organized crowd that comes together, driven by the common passion for football.

Whether one is interested in football or not, one must admit that those moments of truth were simply fascinating in their boldness, syntax, poetry and radicalism. For example, in 2018, the song of the USMA (Union Sportive de la Médina d'Alger), “Casa d’El-Mouradia”, became a great success. It was a nod to a popular TV series (2) and to the district where the presidential residence is located, and after the “Ouled el Bahdja” (3) collective covered the song, everyone believed that it had become the hymn of the “Hirak”.

It is probably the thousands of football supporters who broke the wall of silence on February 22, who gave courage to those who were still reluctant to participate in the movement. It wasn’t only an unprecedented event in Algeria, both in its scope and duration, but it was also without bloodshed, which is meaningful in a country still traumatized by its past.

That Friday, apprehension filled the air, as it always does in our policed territories. However, the number of demonstrators and their explicit pacifism left the police helpless, waiting for orders to attack and disperse. The orders obviously never came.

Casa d’El Mouradia

And why not transcribe it here, this hymn, in the same way that the so called “digital generation” has chosen to write it? On the website of the football supporters, the poem mixes Latin characters with Arabic numerals, which shows that the revolution is, first and foremost, a revolution in language. The “derja”, the vernacular language, or the “tongue of the street” as the purist literati describe it with some discernable contempt, has proved on this occasion that it was more than suitable and capable of saying everything we needed to say about our complexities, and in a way that was legible and well-understood by all.

Sa3et lefdjer ou ma djani noum

Rani nconssomi ghir bchwia

Chkoun e seba w chkoun nloum

Melina lem3icha hadia

From the first verse of the poem, we understand that the song is about a young man from a working-class neighborhood. He is insomniac, and has stayed up all night, until the “Azan” (call) for dawn prayer. He’s poor because he sparingly consumes the little hashish he has, lost in existential questions about the causes of his misfortune, moving from “I” to “we” as he declares that “We are fed up with this life!”

F louwla n9olo djazet

7chawhalna bel 3ochriya

F tania la7kaya banet

La casa d’el mouradia

The story here turns into a history lesson: In the beginning they screwed us up, by scaring us with the “the decade” (of the civil war), but in the second term, things became much clearer. We were living in “la casa d'El Mouradia”, as in the Casa de Papel, the famous series about a money heist.

F talta lebled chyanet

Bel massale7 e chakhssia

F rab3a l poupiya matet

W mazalet l9adiaa

In the third term, the country lost weight from the continuous bloodsucking by private interest. And, in the fourth term, the puppet (“Bouteflika”), yet the story doesn’t end there.

Wel khamsa ray teswivè

Binathoum ray mebniya

Wel passé raw archivé

La voix ta3 l7ouria

Then they plotted amongst themselves and announced the fifth term, but the past is archived inside the voice of freedom.

Viragena lhadra privé

Ya3rfoh ki yt9iya

Madrassa w lazem cévé

Bureau ma7w el oummia

The “Virage” is the section of the stadium where the ultras are seated. There, we speak in private to each other, the song continues, and it's when we throw up our words that they finally recognize us. It's a school, and you’ll need a CV to get into it. It's a literacy class…

The song has a catchy ring in the ear and its metaphors are beautiful. It's both personal and collective, and it crystallizes the ideas that were brewing in that moment, summing up all the things that people wanted to say but didn’t have the words to express.

Since the beginning of the Hirak, the song was chanted and repeated not only by the supporters of the USMA, but also by those of the CR Belouizdad (CRB) in the east of the capital, and of those of the Mouloudia Club d'Alger (MCA) in the west… The fact that the same song was endorsed by rival clubs already indicates a paradigm shift.

Soon after, everyone was repeating the song: the young and the old, from the fancy neighborhoods to the slums, the Francophone bourgeois who work in advertisement, the mothers who hope for a better world for their children, populists, neo-nationalists, and Berberists… It was as if, suddenly, we all agreed on the interpretation of our history as explained by this song, and thus, we were able to draw the same conclusion: “No” to the fifth term!

It is probably the thousands of football supporters who broke the wall of silence on February 22, who gave courage to those who were still reluctant to participate in the movement. It wasn’t only an unprecedented event in Algeria, both in its scope and duration, but it was also without bloodshed, which is meaningful in a country still traumatized by its past.

In the raging street, new slogans were pouring out of every corner in an outburst of collective creativity. Some slogans bravely attacked the police who were deployed everywhere in the streets: “No fifth term Bouteflika!”, “bring the Search and Intervention Brigade (the bad guys then), Bring As’aiqa (the special forces of the gendarmerie)” … There were also calls for fraternity: “The army and the people are brothers”, “take off your army cap and join us!”. And, of course, there were chants against savage capitalism, “you have devoured the country, you gang of thieves!”

A few banners read “No to “hogra” (contempt)”, “No to injustice” or “Peaceful demonstrations”, repeating calls for pacifism as a mantra or a protective shield, a desire to avoid any possible violence.

References to global pop culture like Game of Thrones or the Simpsons were superposed with images of popular actors like Athmane Ariouet and Inspector Tahar.

In the rallies, the emblematic national flag was raised at the tips of fishing rods or worn as a cape, acting both as a symbolic stance and as an armor. Its presence as such was an attestation to the nobility of the people’s feelings at a time when the protestors still didn’t know whether the police were going to act with hostility or not. In fact, the police weren't too violent, and thankfully things did not end in a bloodbath. They used a few teargas canisters and water cannons to block those who wanted to reach El Mouradia. They also used the “Nimr”, a machine mounted with powerful speakers that emit such an unbearable sound that would certainly disperse any demonstrators away, within the frameworks of “democratic crowd management.”

Certain rites and routes were established. In Algiers, the rallies departed from the popular parts of the east and west of the capital after Friday prayers, to converge in the center of the city amidst its huge Haussmann buildings. It had become something like a pilgrimage which had its holy landmarks.

The Hirak was as joyful as a carnival, a spring bacchanal, and a nationwide visit to all regions that emanated a contagious gaiety, with its rhythmic choirs and vibrant hearts. Week after week, the movement established itself as a lucid reality that declared that there was an unprecedented event unraveling indeed. It was all engulfed in a sense of freedom, pride, irony, and the incredible pleasure of the feelings of togetherness and strength which implied that perhaps we could really be invincible.

The Hirak in Lockdown Algeria

02-02-2021

Loud voices rose from our cities, saying that we were all brothers and sisters, that we loved this country, and that we claimed our history. We held the photographs of our faithful heroes: Ali La Pointe, the fearless young man who died a hero in the battle of Algiers; Benmhidi as he stood with a smile on his face in the hands of his executioners; Hassiba ben Bouali, the beautiful martyr who chose death over surrender… We also held up the old flags of the revolution, those precious relics taken out of the cupboards onto the streets… In short, we would no longer allow ourselves to leave Algeria in the hands of a group of criminals, when we are the descendants of a people who had led one of the greatest revolutions of the last century.

It was a collective poem that made perfect sense as it was taking shape, carried by thousands of voices that chanted in unison:

A republic, not a kingdom

Ouyahia must leave

The people want neither Bouteflika nor el Said

Bouteflika, Ouyahia, a terrorist government

We are fed up!

Ouyahia, you donkey, Algeria will not end up like Syria (which was what Ouyahia threatened)

It’s a popular movement not a partisan one

Allah Allah ya baba (a popular tune), we’re about to get the gang

Hey, ho! Remove the gang and we’ll be fine!

They sold our country to the traitors

It’s our country. We run it as we please.

Corrupt government, depraved regime!

We are not idiots!

Oh, Moustache, we’re not well at all! (The military riot control vehicle is known as the “Moustache”, as it carries a crane that hangs on its front like a mustache)

We’re not scared! We’ll be here every Friday.

Hopes and disillusions

As time went by, certain rites and routes were established. In Algiers, the rallies left from the popular parts of the east and west of the capital after Friday prayers, to converge in the center of the city amidst its huge Haussmann buildings (4). It had become something like a pilgrimage which had its holy landmarks: the large post office and its steps, a colonial building in an oriental style, Avenue Pasteur and the hospital in front of which everyone becomes silent so as not to disturb the patients, the stairs along the Omar Racim High School which became an improvised stage for the chants of the young ultras who impose their codes, looks and language on the middle class demonstrators who let them be… There’s also the university tunnel with its exciting reverb effect on songs and ululations, Place Audin, and finally the return to the university, where fixed groups of students gather on the wide sidewalks, with Trotskyists demanding a Constituent Assembly and feminists establishing a “square”, until these groups were soon joined by the families of the detainees of the Hirak.

Boys perched on the square fig trees all along the streets, looking like some strange and happy hanging fruits. There were banners, posters, incongruous creations and curious pavement scenes: men and women carried their demands and their hopes on their backs and in their hands. They thought up slogans and wrote or calligraphed them on banners and cardboard signs at night, in Arabic, of course, but also in English, French, or using a mixture of these languages. It was, after all, a generation that has benefitted from free and compulsory education for sixty years, and which now intended to use it.

The Hirak was as joyful as a carnival, a spring bacchanal, and a nationwide visit to all regions that emanated a contagious gaiety, with its rhythmic choirs and vibrant hearts. Week after week, the movement established itself as a lucid reality that declared that there was an unprecedented event unraveling indeed.

Yes, we want to smile and look decent. Our movement is diverse, trans-generational, and trans-class. People who are differently abled were also there with us, merging with the crowd in their wheelchairs, becoming one body with everyone, in a touching patriotic scene. The men in the squares watched their language and refrained from speaking profanities, as if there was a tacit agreement among the demonstrators to make everyone feel comfortable, which was a striking reality given that our streets are usually male-dominated spaces whose soundscapes are full of references to the male penis and the mothers’ vaginas!

Yes, we are still intoxicated with the joy of this incredible thing that is happening to us, as if we have abandoned every doubt and mistrust between us, believing that we could finally be one people, together and different at once.

The tradesmen realized the absolute pacifism of the crowds, as not a single window had been broken in the market. Everyone cleaned the streets after the demonstrations and the city was always left in mint condition, so the stores reopened in the adjacent streets, and we were able to find food and drinks, and buy flags and banners in a safe atmosphere… Indeed, those were some of the most beautiful weeks of our lives; we were happy and we dared to dream.

During the Hirak, the subjective “I” was also manifesting, revealing itself as the story of the ambitious citizen, the young man hitherto stifled by overwhelming words and ambiguous collective notions, such as “the popular masses”, “the people”, “family”, “tribe”, “students”, “women”, “the youth and the old”, “the Kabyle”, “Arabs”, “Islamists”, “democrats”, etcetera.

In those crazy days, one of the big changes brought about was in our relationship to the image (5). In the age of the smartphone, everyone is a reporter of a sort. We take selfies to say that “we were there”, but also that we allow - or even enthusiastically ask – others to film or photograph us... This was a rather unexpected affinity in a country whose people were hitherto wary of cameras, as if afraid of having their souls snatched away from them or laid bare for all eyes to see.

During the Hirak, the subjective “I” was also manifesting, revealing itself as the story of the ambitious citizen, the young man hitherto stifled by overwhelming words and ambiguous collective notions, such as “the popular masses”, “the people”, “family”, “tribe”, “students”, “women”, “the youth and the old”, “the Kabyle”, “Arabs”, “Islamists”, “democrats”, etcetera.

We were there as living proof of what Jean Sénac, the unique Algerian poet who was assassinated in Algiers in 1973, had called “citizens of beauty". On YouTube, a very long film in pieces is just waiting to be edited into one piece. It comprises thousands of points of view, a thousand cameras, and a thousand angles for of the same event.

Finally, Bouteflika fell on April 2nd. We saw him on TV in a gray Djellaba, looking furious as he announced his compliance.

“They must all leave!”

A news TV station from “our neighbors to the East” comes to broadcast live from Place Audin and film some cars honking with joy. The reporter talks in standard Arabic, blabbering generalities about the people’s satisfaction with Bouteflika’s departure, and that's where Sofiane, a young pizza maker from the neighborhood, jumps into the frame. Out of nowhere, he imposes himself on the camera and declares in “derja” (colloquial language): “No! We are NOT satisfied! They must all leave!” Taken aback by his interference, the reporter then asks the young man to “translate what he said in Arabic”, to which he unwaveringly replies: “this is our language”, as if saying “it’s not my problem, you should make do with that…”

Immediately, Sofiane becomes an icon; an image of a radical “Hirakist” (or revolutionary) who not only claims his mother tongue when he speaks, but above all, gives the people who are tired of everything a simple, yet powerful slogan, in a language that cannot be translatable in its unique essence: “yetnahaw ga3” (“They must all leave”). To him, it was not a question of overthrowing Bouteflika alone, but the entire “system”, which is obviously a much more complicated matter.

Meanwhile, the army chief assumes control. General Ahmed Gaïd Salah unexpectedly enters history, arresting many corrupt civilians and soldiers while he repeatedly praised the “blessed Hirak”. Nevertheless, the General also planted seeds of division, criminalizing raising the Berber flag, which was until then part of the panoply of flags and banners on our streets, right next to the national and Palestinian flags. That was when this once-harmonious triptych of identity, patriotism and internationalism became infested with divisions, resentments, and marginal debates.

In the middle of all this, the small libertarian, egalitarian, idealist and passionate voice of the “Hirak” was finding it increasingly difficult to make itself heard. Here came the militants of the classical structures, who were blown away by this “Hirak” that owed nothing to them. They stuck their noses in everything, reminding young people that they must not party too much, urging feminists not to be too “pretentious”, and telling leftists that it was not yet the right moment for a social revolution. We shall call these people the “This-isn’t-the-time-for” people… This interference somewhat encumbered the peaceful movement even when it kept its momentum and its ambition of affecting change.

General Ahmed Gaïd Salah unexpectedly enters history, arresting many corrupt civilians and soldiers while he repeatedly praised the “blessed Hirak”. Nevertheless, the General also planted seeds of division, criminalizing raising the Berber flag, which was until then part of the panoply of flags and banners on our streets, right next to the national and Palestinian flags.

Week after week, the slogans were changing. “Free the prisoners”, and the clearer, angrier shouts of “Generals, to the trash”, along with slogans about everything, from “an Islamic state!” to “Magharibia, the channel of the people!”. Thus, contradictory groups and sub-groups emerged, most of the protestors deserted the daily rituals for a while, while random arrests led to the creation of support committees for those incarcerated in the unbearably long preventive detention.

On December 12, Abdelmadjid Tebboune was elected president, which was not well-received, given that the election was widely boycotted at the time. Tebboune came from the same ancient entourage and generation of his predecessors, and thus, he wasn’t the one to satiate the most radical of the “hirakists”.

A short while after, Ahmed Gaïd Salah passed away on December 23. His passing was perceived as a symbol of the death of the octogenarian power class, which seemed to cling on to power indefinitely, while the youth of the country screamed their hearts out in the streets.

In the interim, the police banned us from all the symbolic holy sites of our “patriotic pilgrimage”; from the stairs of the Post Office to those of Avenue Pasteur. They even banned us from passing through the “mystical” tunnel. We grew accustomed to walking within the confines of the walls made by the stacked police vans, which were lined up side by side to create narrow passageways or block roads and ruin our collective jubilation as they trapped us between the plexiglass shields and blue helmets. And in a pathetic attempt to control all communication, the authorities cut the internet connection or disturbed it as soon as the crowds took to the street.

Naturally, these facts were denied by the “Hirakis”, who wishfully convinced themselves that the spirit of 02/22 was still blazing and alive, that there was no dissent in the ranks of the “Hirak”, and that change was still possible as long as the people remain united. However, there were certain heavy parties within the movement which had harsher ideas, words and slogans. We even took the liberty of dubbing each other “traitors”, “agents” and “children of France”. We refused to compromise or engage in any dialogue, and declared that no one person or group could represent the movement or speak on its behalf, all while growing exhausted from continually demanding the release of the prisoners of conscience.

Matters were only exacerbated by religious and identity fanatics, and even army supporters. Then came the Coronavirus pandemic, like a global ally of the police regimes, putting an end to the “Hirak” in the middle of March, when the quarantine was announced.

Epilogue: A symphony for a new world

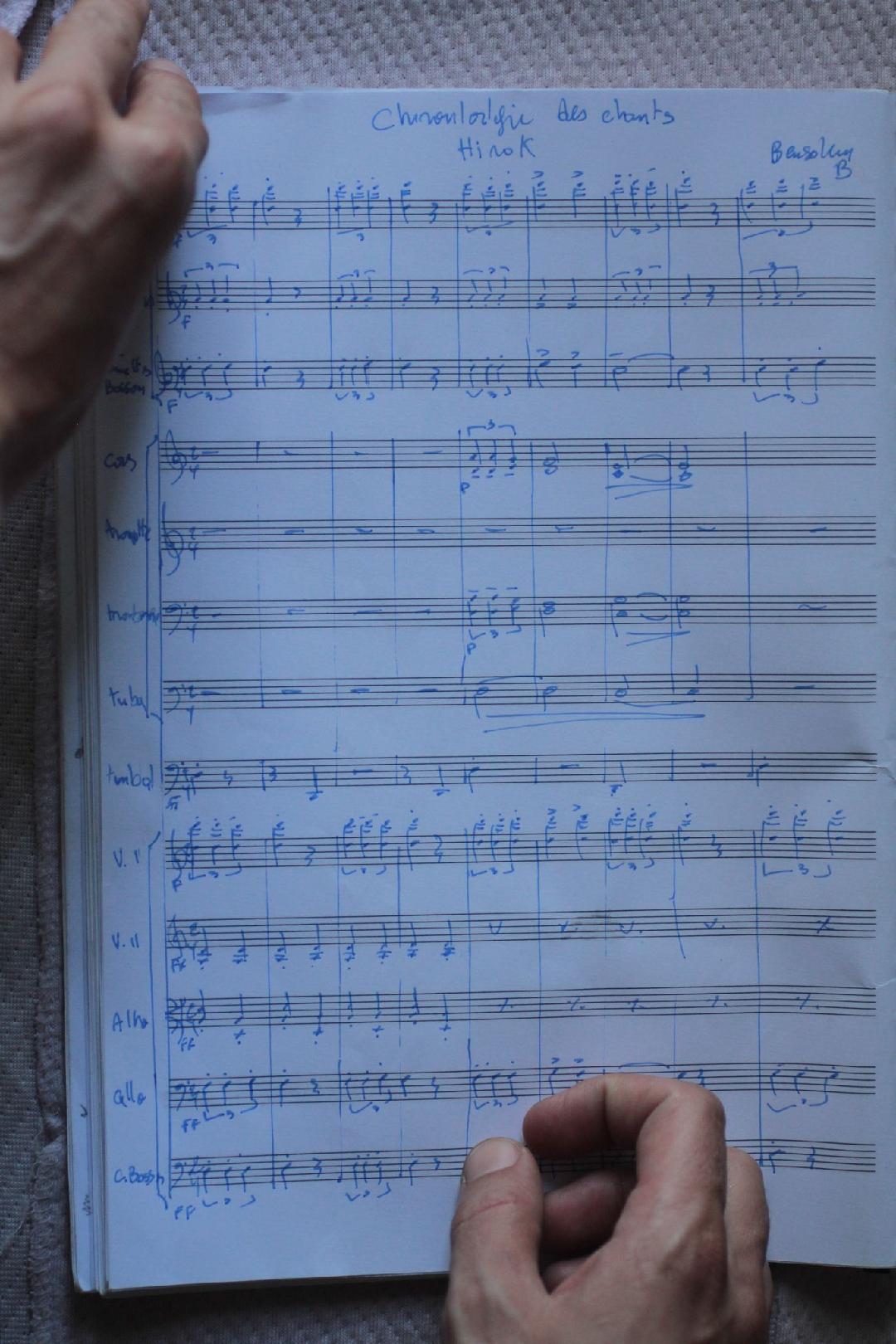

Abderrahmane Bensalem is a musician, his instrument is the oboe and his friends call him “Bahr”. He’s a graduate of the École Supérieure de Musique, a member of the youth symphony orchestra, and a composer in his spare time, and to him, the “Hirak” was translated into a haunting music that lives in his head. Far from the political speeches, his ears only heard an incredible soundtrack of rhythms that expressed collective trance. It was the spirit rather than the word, which presented us a choir from a country and a continent that has played all of its instruments, over the course of one year. From the Krakebs of the Aissaoua (an iron rhythmic instrument), to the Bendir (traditional drum) of the Kabyle women who sang in the squares like Cassandra. Those were the sounds of the harsh times, fear, hunger and resistance; the vuvuzelas of the African stadiums, the drums, Derboukas, clapping hands, ululations, and sirens of police cars... Bahr decided to work with this haunting soundscape which we have come to know all too well, and turn it into an orchestrated symphony.

On his table, music scores are piled up everywhere. When listening to a short clip of it, something essential remains afterwards. Words and slogans are no longer necessary, as we instantly recognize in the crescendos and melodies of the strings or the woodwinds the great symphony of the Hirak, its beats, its syncopations, its rage, its hopefulness… The music is composed purely of the harmonics and the pulsations of a people who had once dared to dream of a better destiny.

Today, in this land of perpetual unexpectedness, no one can predict the future of the Bahr’s ambition. Will his music end up as a requiem, a hymn to joy, or a little piece we can listen to in the nights after the return of the normal, for better or worse - even if deep down we already know that it will always be a little better and a little worse, as life always is? Still, with a resilient heart, we shall always be hopeful that the people will one day lead their own symphony however they please.

A testimony

Khadidja Markemal: “As a photographer, there is a line that separates what was “before” the Hirak and what was “after” it.

Khadidja Markemal is a professional photographer. For a year, she has attached herself to a group of young football supporters, whom she has adopted just as they have adopted her, by the grace of photography.

At first, Khadidja was cautious and only used her smartphone to take photos in demonstrations, before switching to her professional camera at the request of young protestors who wanted HD quality pictures in order to immortalize the magic of those moments. She testifies that no border, no man or woman, neither rich nor poor, could have countered the movement which was led by the free citizens who not only claimed back their history, but also left their own traces on it.

*******

“If it weren’t for the Hirak, we probably would have never met. We met each other in the clashes that happened in the beginning, between the rubber bullets and tear gas canisters. Then, we ended up at someone’s house. Spontaneously, I fraternized with these young people. I wanted to understand the Hirak, and I wished to meet with groups of people, not with an individual or a tendency, in order to witness the moment without bias. We saw the Africa Cup together and shared moments of our lives. I went to the trial of one of them, they celebrated my wedding with me, and they invited me to the anniversary of the Mouloudia (football club). We realized that we were basically of the same young generation; that of the children of the year 2000.

I found myself for the first time among a group of people where I was given complete trust and asked to take and share photos of them, even though I was the only girl in the squad… I loved it. They liked to see themselves in photos, even in bad ones. They also gave me directions to make them look cool and stylish in their portraits.

As for those young people who usually played their musical instruments in the stadiums, they weren’t just walking around and making noise. The “audience” of the Hirak was important to them. They lingered at the entrance to the metro station at the post office, nervous and excited, doing their best to perform well for the crowd, like real artists would. One of them lost three fingers tapping on his Derbouka; he was a veteran performer who had joined “the Houma”- the neighborhood squad.

As a photographer, I see that there is a line that separates what was “before” the Hirak and what was “after” it. It was as if the public space was opening up to us all at once. Our relationship to photography has developed and we learned to see better, to watch better. We became more tolerant and recognized the nuances in things. People no longer viewed us, photographers, as show-offs, liars or intruders, but as intermediaries in representing our realities. Unlike the people, the police were always suspicious of us. They often stop me to ask me whether I sell my photos abroad. To them, my photographer badge or artist card issued by the Ministry of Culture meant that I was just allowed to take photos at weddings and fashion shows, in interior locations; not in the streets, where my work turns into journalism, and therefore becomes political. For them, the photographer is the enemy. It’s an outdated mentality. Anyway, my images were published everywhere. Many journalists even used them without bothering to inform me, illustrating the essays they decided not to share with me beforehand. We do not really control how the material is shared or appropriated in the media and social networks, but I shared my photos as witnesses to that moment, not to profit off them.”

• All the photographs in this text were taken by the photographer Khadidja Markemal.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabah Jalloul

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 07/01/2021

1- An Algerian activist who lives in Germany. He is very active on social media and sheds light on the financial and sexual scandals of Algerian politicians.

2- A reference to the Spanish series “La Casa de Papel”.

3- The song in the stadium: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L3IcT5mFxFs

4- Haussmann was the governor of Paris from 1853-1870 under Napoleon III. He remodeled the city and made wide boulevards, which was considered a modernization. He also aimed to get rid of the insurrections that characterized the nineteenth century in France.

5- See the attached testimony of photographer Khadidja Markemal