This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

To speak of “slums” is not necessarily to speak of geographic/residential areas that spring in the middle of nowhere, or grow and live in seclusion from social dynamics. At least that is not the case in Tunisia. To begin with, some old and well-established neighbourhoods, located by the peripheries, have gradually deteriorated. Unemployment and impoverishment increased there as those neighbourhoods became overcrowded with the migration of residents from other classes and regions. Official, human, financial, and institutional presence have also been diminishing there, and so these neighbourhoods turned into marginalised housing blocks, despite their proximity to the centre.

In parallel, some housing complexes had been originally constructed without proper licencing in rural peripheries, atop agricultural lands or near industrial areas by the city suburbs. These would gradually grow in size and population to such a point that the state had to give in to reality on the ground and “legalize” them. They had to try and assimilate them into urban development plans but without providing the minimum of services or facilities, or any plan to develop or incorporate these new residential neighbourhoods into development policies or social recovery. Such blocks then turn into “regulated” and “legal” slums that the state recognizes, while it fails to recognize any of their residents’ rights.

The third kind of “slums” goes unnoticed and unmentioned; they’re “invisible” slums, not because they are located in isolated areas or faraway from city centres, but rather because they spring and grow in the hearts of regulated residential areas inhabited by middle-class residents. Such a phenomenon characterizes the big cities in the coastal eastern central region: Sfax, Sousse, Monastir, and Al-Mahdia. Alongside the provinces of Tunis and Nabil (north-east Tunisia), this region is considered one of the most prosperous Tunisian regions, due to the density and diversity of economic activity and the relatively developed infrastructures that suffer from weak economic configurations and state marginalisation. The neighbouring central western region (Kairouan, Sidi Bouzid, and Kasserine governorates), which nationally has the smallest percentages on record of development, is the primary source of migrants towards the governorates of the centre-east. Such a turnout has created a large demand for low-rent housing, and thus paved the way for a new phenomenon: housing complexes for impoverished newcomers that look like slums, which arise and develop in the heart of regulated neighbourhoods mainly inhabited by the middle class. Even if present in most eastern central governorates, this phenomenon is much more prevalent in the Sfax governorate, and specifically in its northern and western suburbs, close to its main city.

In the beginning, there was “Al-Ghaba”

Until the late eighteenth century, most Sfax city inhabitants used to live within the borders of the old city, with its Islamic-Arabic architecture (the Arab town, as it’s now called) or in the nearby neighbourhoods called “arbaad” (squatter lands). With the demographic and economic development, especially with the incoming French colonialism, inhabitants had to gradually move out of the city and head towards the woods (“Al-Ghaba”) in the northern and western parts of the city (2 to 10 kilometres away). Al-Ghaba are immense terrains comprising gardens called “Al-Jinan”, and are known for their almond trees, vineyards, citrus trees, and other types of fruit trees. Most Sfax families that used to inhabit the old city used to own a garden where they would build a home called “Al-Burj” and move in at the beginning of the summer season – to pick fruits as well as to enjoy nature, greenery, and fresh air – then finally head back to their primary homesteads in autumn. Gradually, secondary homes became their primary, and Al-Ghaba turned into a residential area around which commercial centres and artisanal trades would form, but without severing ties with the old city. This area, just a few kilometres away from the city centre, would develop to become urban centres with their educational institutions, infrastructures, administration, artisanal spaces, factories, and otherwise, and would acquire a huge demographic and economic importance. Al-Ghaba is no official name or regulated administrative/territorial division; rather, it is a popular and local name given to a vast area whose neighbourhoods share many demographic, economic, and sociocultural characteristics. They extend over three mutamadiyas (Arabic for delegation, which is an administrative division a little larger than a municipality and smaller than a governorate): Saqiyat Dair, Saqiyat Zeit, and Western Sfax, 3 to 10 kilometres away from Sfax city centre. It may also be said that at the beginning, Al-Ghaba used to be an agricultural zone, but later turned into an urban centre with several small towns.

Some housing complexes had been originally constructed without proper licensing in rural peripheries, atop agricultural lands or near industrial areas by the city suburbs. These would gradually grow in size and population to such a point that the state had to give in to their presence and “legalise” them. Such blocks then turn into “regulated” and “legal” slums that the state recognizes, but without recognizing any of their residents’ rights.

Al-Ghaba is divided into main roads, neighbourhoods, and centres (commercial, artisanal, and service-based complexes). In social and class terms, the more established and middle class old Sfax families remained prevalent in Al-Ghaba, all the way until the 1980s. During that period, the country began to test out the results of economic developmental policies that were launched in the 1970s, all based on marginalising agriculture in favour of tourism and light industries. Furthermore, the country would gradually begin to drop its social responsibility and reduce its social expenditures. Such a policy forced large numbers of farmers and their children – as well as other inhabitants of rural and marginalized areas – to leave agricultural labour and lands to look for work in the cities, which had been living through an economic boom and guaranteed a better quality of life.

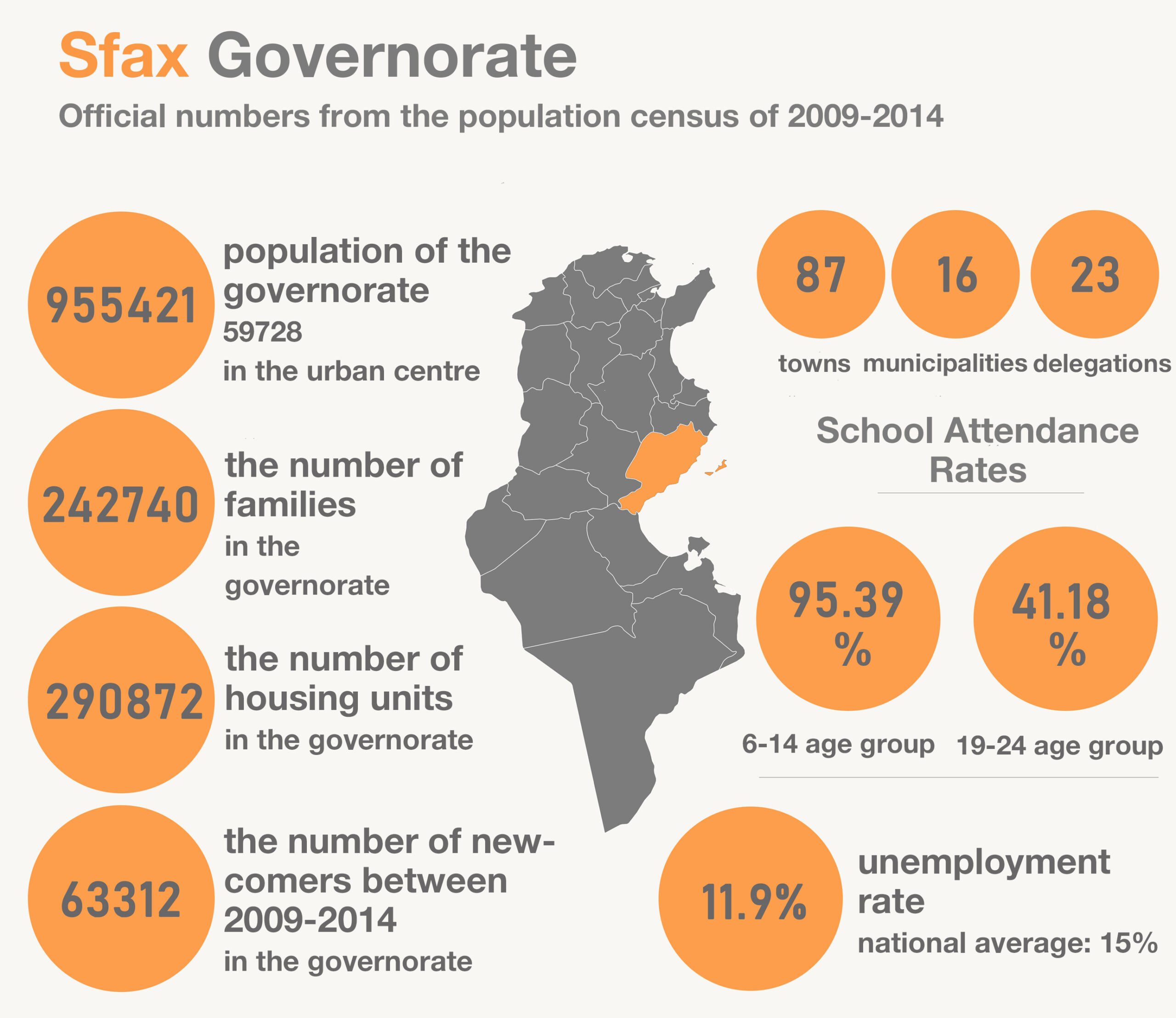

The eastern central cities, including Sfax, would thus become the main destination for migrants. Notably, Sfax is the second largest governorate in Tunisia, and functions as its economic capital and a bridge between its south and north: thousands of factories, artisanal workshops, commercial and service-based institutions, as well as an airport, fishing and commercial ports, in addition to millions of olive and almond trees. This area also serves as a healthcare destination (with two public university hospitals and tens of private clinics) and an educational hub (twenty academic institutions, and hundreds of primary, elementary, and high schools that produce the highest grades in national exams.) Naturally, rental in the city centre and nearby neighbourhoods is quite expensive and unsuitable for impoverished migrants looking for work. In parallel, popular neighbourhoods are already crowded and rarely have any rental availability.

Al-Ghaba thus offered a compromise. Neither too close nor too far from the city centre, it is a vast area that stands out for its well-spaced horizontal houses, and is also connected to the main facilities and services. Living in this area enables migrants and newcomers to quickly find work while paying low rent, as the area is only a few kilometres away from many industrial areas: Baudrillard 1 and 2 in the eastern part of the city, Qabis Road in the south, and Sidi Saleh, Hancha, and Amirah in the north. The city, whether the centre itself or Al-Ghaba area, has experienced expansive and continuous construction activity, which attracts a large part of male newcomers and creates movement. Female newcomers, on the other hand, are more prone to work in textile factories and the light manufacturing industries. The large number of rich people and luxury housing in the city has also opened up jobs in gardening, maintenance, and security posts for male workers, and housework for female workers. In parallel, seasonal agricultural work also opens up during olive picking and almond harvest seasons. Newcomer presence remains weak in regulated services and commercial sectors, though, for those with a low level of education. Shadow economy, however, doesn’t care too much for qualifications and is happy to give everyone a chance…

Some old and well-established neighbourhoods, located by the peripheries, have gradually deteriorated. As unemployment and impoverishment increased, those neighbourhoods became overcrowded with migrants from other classes and areas, and so turned into marginalized complexes, despite their proximity to the centre.

Hundreds, then thousands of impoverished migrants arrived into an area originally inhabited by the middle class, which shifted the dynamics and produced new architectural/social conditions…

“Clandestine” houses and “ghost” residents

Migration to big cities also increased as the urban middle class experienced significant changes. Lifting subsidies off of some of the merchandise, liberalising others, reducing state spending on healthcare and education, the unemployment crisis for the academic class, and the proliferation of consumption culture are all elements that pushed a large part of the middle class to look for additional sources of income to offset their waning buying power. One of the solutions they resorted to was renting out their houses. Naturally, though, those in need of an extra source of income to improve their financial situation would not build a luxury house to rent out – that would constitute a failed investment, especially when the demand for rent in that area originally springs from the precarious living conditions of those seeking cheap housing. What’s the way out, then? To rent out dilapidated old houses, some of which were built in the early 1900s, “fixing” garages and storage rooms to turn them into what looks like residential spaces, or constructing new “houses” packed like sardines in size and comfort. A space put out for rent is normally composed of one to two tiny rooms, with a small kitchen and bathroom. Some landlords also rent out garages without dividing them up into rooms or turning them into suitable living spaces. The landlord chooses the cheapest building materials and appliances with the worst quality, including doors and windows (if at all), flooring, lighting connections, water, and sanitation networks (again, if at all). And of course, the space’s conditions will quickly deteriorate, especially since the number of residents occupying it is quite large, as most renters are impoverished daytalers, who cannot afford individual housing, and so share the expenses of the same “house” to lighten their financial load. Quickly, things become unbearable: paint damage, cracked walls due to humidity and lack of ventilation, stoppages in sewer systems, rundown doors and windows, cracked floors, and so on. The problem is that landlords will not carry out repairs or essential maintenance, because they consider those to be extra expenses, while renters are, at the same time, unable to afford them or carry them out on their own. Most often, renters end up accepting reality or leaving one house in search of another. This, however, doesn’t worry landlords as they know very well that demand is on the rise, and that their place would not stay uninhabited for long; other renters arrive, things remain as they are, or rather the conditions of the house become more catastrophic. Then, when landlords do decide to carry out renovations, they do so only with the intention of raising the rent, or even doubling it. Most “homes” in question are unlicensed and their rent revenues are undeclared; they are inhabited by dozens over years, yet not a single rental contract or legal document exists that proves this. It is very easy to identify one of these houses with the naked eye. Should you pass by one of those neighbourhoods, you would note that many of the large and pretty houses there are small concrete masses that look like boxes, built with red bricks, and have yellowing peeled paint with visible cracks. While landlords care for their own homes and gardens, they neglect the homes they rent out in flagrant and humiliating contradiction.

Theoretically, migrants enjoy the advantages of living in an area where essential services are available (healthcare, transportation, and education), power networks, potable water, and sanitation; in reality, however, they live in dilapidated houses and cannot afford basic services; many of them do not even figure in local authority databases – that is, they do not exist officially.

When this type of housing grows in number, reaching dozens, or even hundreds in big neighbourhoods, it means that a small slum neighbourhood is in the making – not as one contiguous mass, but as dispersed units that mushroom from the “native” neighbourhood walls. These units are considered “microcosms” that are based in a few different ties: familial, tribal, and regional.

Namely, with time, small clusters of migrants hailing from the same region or tribe are formed, and relations of solidarity, mutual support, and harmony are created: sharing their houses, providing work, family visits, celebrating religious holidays, and intermarriages. Solidarity might even extend to include another cluster, or clusters, of migrants, by virtue of “strangers to strangers are kinsmen”; likewise, they may turn into disagreements and conflicts for reasons related to job opportunities, tribalism, or even a love affair. All this takes place in a world that parallels the “native” neighbourhood and its “native” residents.

In most cases, such houses are unlicensed and are rented out without signing any contracts; that is, they do not exist in official records and, along with their inhabitants, are not counted in public censuses. Practically, neither the centralized state nor its local authorities know the real number of the residents of such neighbourhoods: thousands of “ghost” nationals whose demographic weight is not taken into consideration when preparing a certain area or when linking it to a public facility. When the time comes for registering kids in schools, for instance, problems arise, as some of those kids are born in other governorates, and their parents have no “certificate of residence”, which is normally issued whenever a rental or property contract is handed in. The same trouble arises when other documents need to be produced, or when handing in demands to the local authority. Many migrants still have their old addresses on their ID cards, and have yet to apply for a change of address at the elections centre in order to be listed in the electoral registry in the province they currently live in. A large number of them is not even officially listed in the centralised electoral registry – that is, they have no electoral clout in the neighbourhood or governorate into which they’ve moved, and hence, no electoral candidate or elected MP would seek to appeal to them to guarantee their satisfaction (and, subsequently, their votes).

Normally, migrants avoid problems and conflicts with the “native” residents as the former are a “minority”. They fear that there might be a high price to pay otherwise, by losing job opportunities, or becoming compelled to move into another neighbourhood. They experience the same fears when it comes to their relationship with security forces, as they are often detained to verify their identities and check whether their names appear in lists of wanted people. Even when the ministry of defence launches compulsory military conscriptions (which it has given up in recent years), these people are the first “victims” and are easily targeted in the cafes and spaces they frequent.

Purgatory…

Although the two “masses” – that is, the “native” residents of the neighbourhood and those who have migrated to it – coexist on the same land, and although the second “mass” continuously grows in number, points of “contact” and the probability thereof are quite limited and circumstantial. The reasons behind such a segregation are many, and most are connected to the original inhabitants rather than the newcomers. The residents of these areas belong to old families, some of whose presence in the city goes back hundreds of years, which creates a profound connection to the place and a sense of belonging and superiority that leads to their reclusion and refusal to mingle with those whom they consider “outsiders”, or strangers. Furthermore, “cultural” and historical factors that pertain not only to the city of Sfax but also to the entire country play their own part. While Tunisia doesn’t suffer from sectarianism or ethnoreligious conflicts, it experiences regionalism and tensions between urban and small-town/rural inhabitants. The more established big city residents submit to no tribal structures, but rather have their own familiar structures, where every family’s status is derived from their old descent, wealth, and influence. On the other hand, most newcomers hail from areas where tribal structures are still present, whether in terms of human relations or customs and traditions.

Furthermore, this “xenophobia” has its own historical and psychological background. There have been conflicts around the land between the city residents and the tribes in its vicinity; that is, in addition to the fear that some tribes would raid the city, which is something that continued to happen all the way into the nineteenth century. Such a charged memory would consider the wave of thousands of newcomers a new type of “raid”, and would accuse it of the increased crime rates and the city’s “loss of identity”. Otherwise, the classist factor cannot be neglected, of course. Al-Ghaba residents are generally from middle and sometimes upper classes, white collars with secondary education, artisans, merchants, and specialised workers, while most migrants are impoverished agricultural workers, with no academic degrees nor technical skills. In addition to all of the aforementioned, secondary factors relate to the demographic composition of the newcomers, their activity, and their relationship with their surroundings. The vast majority of the newcomers are single young men and women, who come to live in conservative residential/familial neighbourhoods, where bachelor apartments are perceived as suspicious. Migrants who arrive as a family would have better “luck” in assimilation, especially if they were to prove their “seriousness” and commitment to certain “moral” values. Furthermore, a newcomer’s connection to the neighbourhood doesn’t develop much emotionally – the moment they find better opportunities (cheaper rent, bigger job potential), they’ll move into another area or sometimes into another city.

In most cases, houses are unlicensed and rented out without signing any contracts. They, and their inhabitants, are not counted in public censuses. Neither the centralised state nor its local authorities know the real number of the residents of such neighbourhoods: thousands of “ghost” nationals whose demographic weight is not taken into consideration.

The two “masses” – that is, the “native” residents of the neighbourhood and those who have migrated to it – coexist on the same land. However, points of “contact” and the probability thereof are quite limited and circumstantial. The reasons behind such a segregation are many, and most are related to the neighbourhood’s old inhabitants rather than the newcomers.

Contact and interaction spaces aren’t many, and are mainly limited to school, when it comes to children, and the mosque, when it comes to adults. School benches create some kind of temporary closeness between the schoolchildren. With time, children grow, and the influence of the “culture” instilled by their families in their minds and souls begins to take effect, gradually growing until it becomes a reproduction of the same mainstream mentality. At some stage, children begin to see each other in the eyes of their parents. Tolerance, equality, accepting differences, and national unity, which schools are presumed to plant in young minds, do not last long in the face of discrimination culture and superiority and inferiority complexes that society produces. Mosques, however, are another story. The nature of the place presumes that all people are equal, and that one can only be better than others when it comes to devoutness. Besides being the only space that guarantees “equality”, mosques have other social “advantages” too. In a small, closed, and conservative society, religiosity makes it easier to be accepted into a group. In the case of “newcomers”, to whom accusations of theft in the neighbourhood are often stuck, frequenting the mosque and showing religious and moral commitment in daily life makes a good impression on the “native” residents, and facilitates acceptance or even assimilation. However, one must not overstate the role mosques play; as most “newcomers” are single young men and women, that is, not typically of the age or social group that frequents mosques. Of course, whenever prayers are over, each worshipper often heads back home to their own world and back to their social class.

Even cafes do not truly offer mixed spaces – in most cases there are cafes that “newcomers” frequent while the rest of the cafes belong to the “native” residents of the area. Naturally, this state of affairs isn’t imposed by force, but is rather more like a semi spontaneous arrangement. Then, even when everyone happens to sit in the same café, it doesn’t necessarily mean that relationships or friendships are being made. Tables where the “natives” sit can easily be distinguished from those at which “newcomers” gather: by their attires, accents, and even their “buying power”. Cafés frequented mostly by “newcomers” do not simply exist to provide entertainment and leisure – rather, they primarily function as welcome centres that offer guidance. Newcomers often have no knowledge of the area and enjoy no strong connections there. They thus sit in a café for days, then gradually make connections, especially with newcomers that hail from the same area they had originally come from. These relationships make life easier and mitigate feelings of homesickness and the sense of estrangement.

Such cafes are also usually located in the peripheries near the “centre” (a complex of shopping centres, administrative headquarters, and others) – and for good reason: job opportunities. Whenever a resident of the area needs a daytaler for construction, gardening, or other such work, they first head towards the “station”, where daily labourers wait for a job offer, or towards the café frequented by the “newcomers”.

Naturally, all such geographic/architectural, classist, and human divisions render relations between the two “masses” (the first being semi constant and the second being in constant flux) very feeble. Even social and religious occasions, which are supposed to bring together residents of the same neighbourhood, have no real effect. The “natives” of the neighbourhood rarely invite their “newcomer” neighbours to their weddings – this only happens once they’ve lived there long enough to gradually assimilate and establish real relationships. As regards the newcomers, they prefer to have their weddings (and funerals) in their areas of origin, while most of them head back there during the religious holidays (especially during Eid al-Adha). In other words, it is very normal for two families to live next to each other for years while their relationship doesn’t go beyond exchanging hellos. Intermarriages are equally a rare occasion, and usually take place against the families’ (especially “landowners’”) wishes and without their blessing.

The case which we have studied through the lens of its socioeconomic dynamics has tangible repercussions on tens of thousands of Tunisians. They inhabit regulated neighbourhoods that are located in “privileged” areas in close proximity to public facilities, urban centres, and all sorts of services, but live in homes and living conditions that aren’t too different from those we find in the “typical” slum. Residents of these neighbourhoods might even have it worse than the inhabitants of slums and irregular settlements, who often offer each other neighbourly solidarity (regardless of their usual disagreements), without mixing class and social status into the lot – these notions remain “out of sight, out of mind”, as the proverb goes. On the other hand, the abovementioned neighbourhoods are home to contradictions, conflicts, and sensitivities that are either rooted in centuries earlier or have been created following Tunisia’s independence – due to the state’s failed and destructive economic and developmental policies.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 26/09/2019