This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

The year 2019 will certainly remain a landmark year in the history of Algeria. After breaking the wall of fear on 22 February, the Algerian people succeeded in removing Abdelaziz Bouteflika, a seemingly irremovable president, in March. The man is gone, but his regime is still alive, even if it is shaky. The country's official date of independence was in 1962, but in 2019 the people made their own independence. For more than three months, millions of people have taken to the streets every Friday, proclaiming their desire for profound change in the regime, while thousands of students expressed their rejection of the prevailing system every Tuesday.

This peaceful protest movement, the Hirak, has already achieved two major victories: the resignation of Abdelaziz Bouteflika and the cancellation of the presidential election, which was to take place on July 4th under the auspices of disgraced leaders. This "Revolution of Smiles" demands the departure of the entire ruling class. It paves the way for the people to choose their new president in all transparency, to elect a chamber of deputies that truly represents them, instead of being a sounding board for the regime, and to establish a second republic and a judicial system free of all ties to power. The Hirak does not want all these elections to take place under the supervision of men who were part of the abolished regime; it also demands the prosecution of all the “Mafioso” men who have embezzled the country's wealth for their own benefit. These are only the most basic demands of the Hirak.

That being the case, was such an upheaval foreseeable? It is certain that at the time of the events that marked Bouteflika's four terms in office, it was impossible to pinpoint the moment when everything changed. It was, nevertheless, foreseeable that the chain of events could only lead to the current situation. We can therefore answer the question with “Yes,” because the scenario that Algeria is currently experiencing was a logical outcome. Like all dictatorial regimes, the Bouteflika regime itself nourished the seeds of its self-destruction, as internal struggles were some of the core reasons for its demise.

The Rise of Bouteflika

Bouteflika was elected in April 1999 under suspicious circumstances, after the generals pressured the other six candidates to withdraw from the presidential race on the eve of the election. Bouteflika sought to escape the generals’ tutelage by soliciting support from abroad, in particular from the President of the United States. But benefiting from the support of the President of the world's leading power comes at a high price. Bouteflika’s opportunity to realize his plans was provided by the September 11 attacks. He made two consecutive trips to Uncle Sam's in the last quarter of 2001, in an attempt to make a deal with George W. Bush: Algerian oil plus making the wealth of information held by Algeria on Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb available for the US, in exchange for Washington’s support. Greedy for power, Bouteflika put his childhood friend and Minister of Energy, Chakib Khelil, in charge of drafting a new law on hydrocarbons, based entirely on the new US doctrine on the subject.

Under the guise of adapting the energy sector to the operating conditions of a free and competitive market economy, Khelil was asked to seek the assistance of the World Bank and US consulting firms to develop a text that took up, point by point, the new US provisions in this area. As soon as he arrived at the White House, President George W. Bush entrusted a working group chaired by Dick Cheney, former CEO of Halliburton and now Vice President of the United States, with designing this doctrine.

2019-2020: Algerian Power versus the Hirak

10-02-2021

Unsurprisingly, the new Algerian law adopted the same objective as that of the Americans, that is, transferring ownership of oil and gas deposits belonging to the national companies of the producing countries to the multinational oil companies, the majority of which are American. The main provision of the new Algerian law stipulated that any foreign company to which an exploration license would be granted had to offer the national company Sonatrach a 20 to 30% stake and that the latter would accept or refuse this proposal within 30 days. The response of the national company could only be negative, given that the required investment was generally high and that the technical data, available at this stage of the operation, were very approximate. This meant that all oil and gas fields would eventually be under US control.

Like all dictatorial regimes, the Bouteflika regime nourished the seeds of its self-destruction, with internal struggles being some of the core reasons behind its demise.

Bouteflika made a deal with George W. Bush: Algerian oil plus making the wealth of information held by Algeria on Al-Qaeda available for the US, in exchange for Washington’s support and protection.

Opposition to the law from the Department of Intelligence and Security [DRS] and the General Union of Algerian Workers [UGTA] led Bouteflika to freeze it in 2003 because it jeopardized his re-election for a second term. He, then, passed the law the day after his re-election, before rescinding its most controversial provisions in 2006. Out of spite, having lost the tug-of-war with other Algerian establishment structures, Chakib Khelil developed another law whose provisions were a real deterrent to any foreign investor wishing to set up in Algeria.

Oil Plus Power

Abdelaziz Bouteflika has always used Algerian oil and the income it generates as a means of consolidating and perpetuating his power. Oil revenues allowed him to buy social peace by subsidizing a certain number of basic products as well as fuels; they also served the purpose of allowing the clan of generals and their henchmen to gorge themselves with commissions on all the contracts concluded by the state, including those very important ones awarded by the National Hydrocarbons Corporation. Hundreds of millions of dollars were shared by all these corrupt people who only wanted one thing: that Bouteflika remains the head of the state as long as possible.

Corruption has been Bouteflika's tool of governance. It has allowed him to buy the support of crooked businessmen, high-ranking civil servants, politicians of all stripes, and members of religious groups. Making cheap consumer goods available to the people was a way to corrupt them. The DRS put the brakes on such activities in January 2010 when the CEO of Sonatrach, vice-chairmen and other managers of the company were brought to justice and imprisoned for a major scandal in which they were involved. The Ministers of Energy, Interior, and Commerce were also dismissed in the wake of the affair.

The new Algerian law adopted the same objective as that of the Americans, that is, transferring ownership of oil and gas deposits belonging to the national companies of the producing countries to the multinational oil companies, the majority of which are American.

Corruption has been Abdelaziz Bouteflika's tool of governance. It has allowed him to buy the support of crooked businessmen, high-ranking civil servants, politicians of all stripes, and members of religious groups. Making cheap consumer goods available to the people was a way to corrupt them.

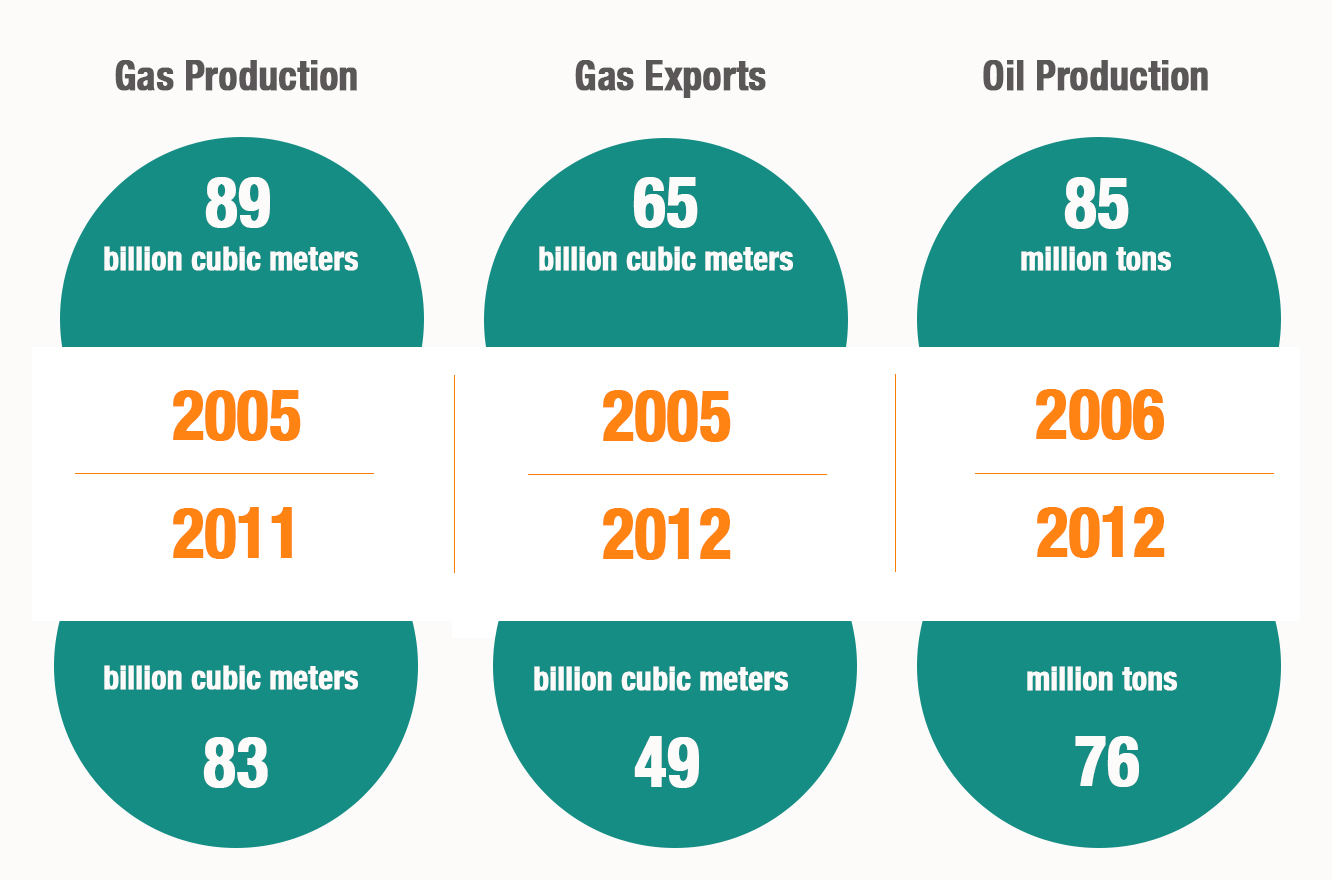

This system worked perfectly well as long as the price of a barrel of oil oscillated in the range of $100 to $140 and Algeria attracted foreign investors. Things started to go wrong in 2011. The first scare occurred when rumors that Algeria's gas reserves were overestimated began to circulate around the world. The new Energy Minister, Youcef Yousfi, denied this and declared that the country had sufficient natural gas reserves to cover both domestic market demands and export commitments. However, the figures are persistent. Algeria's gas production had effectively fallen from 89 billion cubic meters in 2005 to 83 in 2011, while exports had fallen from 65 billion cubic meters in 2005 to 49 in 2012.

The minister had to face the facts and admit that Algeria was experiencing increasing difficulties in marketing its gas at any prices, as the United States was moving from being a major consumer to an exporter, after its intensive exploitation of shale gas a decade earlier. He also admitted that the domestic consumption of natural gas had been on the rise in recent years and that, at this rate, Algeria risked not being able to meet its exporting commitments in the long run. Crude oil production was also declining, from 85 million tons in 2006 to 76 million tons in 2012. This decline had not had a huge impact on the country's financial health, however, as the price of oil was still around $120 to $130 per barrel.

But the downward trend in oil prices over the past year or so had begun to cause serious concern for the regime, especially since the number of security personnel and the expenses of the security agencies, which are responsible for preventing any revolt by the people, were constantly on the rise. Another alarming event occurred when the third tender for the allocation of exploration permits proved unsuccessful in October 2011.

The Crisis

For the Algerian regime, this was too much: the selling price of gas was constantly declining, the mining sector had become unattractive, and there were sales contracts whose terms cannot be honored in the future. It was the whole edifice of power that was crumbling. To remedy this state of affairs, the Minister of Energy announced a new law on hydrocarbons with two essential provisions: the first was a revision of the method of calculating the tax on the profits of oil companies, which would henceforth be based on the rate of profitability of their operations, while the second, intended to compensate for the decline in natural gas production, authorized the exploitation of shale gas.

There were also setbacks due to internal struggles within the regime. The terrorist attack on the Tiguentourine gas plant in In Amenas area in January 2013 made Algeria even less attractive to foreign partners, who began to doubt the effectiveness of the means used to ensure the protection of men and industrial installations. This attack was carried out by a group under the control of Mokhtar Belmokhtar, a terrorist leader who had been considered a DRS man until that time. The DRS had convinced the Americans of the man's usefulness to the point that the latter did not eliminate him, even when it had the chance.

Rumors circulated at the time that the attack was a DRS operation gone wrong. The fact remains that it cost the lives of 70 people killed by missiles fired from DRS helicopters. The Americans then made the Algerians understand that their policy of infiltrating AQIM (Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb) was a failure and demanded that the DRS be swept clean. Only the boss Tewfik Mediene managed to save his head. But the principal consequence of this event was still there: it had seriously weakened the regime. The tension between the Chief of Staff of the Army and the heads of military regions, on the one hand, and the generals of the DRS, on the other, was such that it almost ended in a bloodbath.

The terrorist attack on the Tiguentourine gas field in January 2013 was carried out by a group under the control of Mokhtar Belmokhtar, a terrorist leader who had been considered a DRS man until that time. The DRS had convinced the Americans of the man's usefulness to the point that the latter did not eliminate him, even when it had the chance.

Finally, there was the lack of enthusiasm shown by the oil companies during the 4th call for tenders for the awarding of new exploration permits in January 2014. This call for tenders covered 31 oilfields, 17 of which were located in areas with shale gas. Only 4 licenses were granted, none of which were in shale gas zones. A panic then invaded the ranks of the regime, which saw that this new income, on which it was counting firmly to regenerate the system, did not seem to excite potential partners.

But the greatest blow would come later. During an OPEC meeting on the 27 November 2014, Saudi Arabia imposed its own decisions on the other members of the organization. To regain the market share that had been eaten up by US companies producing shale oil, Saudi Arabia refused any reduction in OPEC production below the current level of 30 million barrels per day. The market reaction was immediate; the price of a barrel of Brent crude oil plummeted from $72 to $57 on the last day of 2014 in just one month.

The Army Opposes the Proposal

In parallel to these events, the opposition parties managed to agree on a minimum demands program for the first time. They created the National Coordination for Liberties and Democratic Transition [CNLTD], which proposed the establishment of a transitional period during which a new President of the Republic would be chosen to replace the seriously ill Abdelaziz Bouteflika. This small window was immediately closed by Chief of Staff Gaid Salah, who responded in the same way he did to a similar request made a month ago, namely that “the army was opposed to such a proposal.”

This was five years ago. Due to their carelessness, their lack of interest in the welfare of the people, and because they have always been obsessed with only one issue - their survival in order to continue to plunder national resources - the mafia henchmen of all sides, civilian and military, of the Algerian regime, have missed noticing the problems accumulating over Algeria. They did not know, or perhaps, they did not want to notice the deterioration of the general state of the country, including that of the hydrocarbon sector that brings in almost all the foreign currency necessary to cover Algeria's plentiful imports, which allowed them to give the people the illusion of living well.

The government continued to import everything and anything. Algerian leaders have never considered a program for the development of the economy based on the work, effort, and intelligence of citizens because, in their eyes, a responsible citizen is a dangerous citizen.

How did the government react to the crisis that was brewing? By incompetence or by the greed of some who wanted to get more commissions, the government continued to import everything and anything. Algerian leaders have never considered a program for the development of the economy based on the work, effort, and intelligence of the citizen because, in their eyes, a responsible citizen is a dangerous citizen. The Algerian citizen must remain a permanent recipient of assistance who believes that maintaining the same "gang" in power is his only salvation. This was the term used recently by General Gaid Salah himself to designate those pillars of the regime, including the brother of the deposed President, who have allied themselves against him and sought to depose him.

Let us not forget that Gaid Salah himself was the most important pillar of this regime during the last 20 years. The government did not understand that the path it had chosen would cause enormous economic, political, social, and cultural damages to Algeria in the more or less long term and that it was equally suicidal for it. For lack of expressing their total rejection of the system, as they have been doing magnificently for more than three months, the people unleashed dozens of daily protests to wrest a few meager financial advantages from the mafia clique and thus recover even a tiny share of the oil rent they shared. The slogans already launched by the youth during these protests showed how much disdain they had for Bouteflika, his entourage, the generals, and the oligarchs who respected neither the glorious past of their country nor their own people. The cowardice, which the rulers had already shown at that time, demonstrated day after day that they had no respect for their own people.

Enough Is Enough

The re-election of Bouteflika for a fourth term of office added to this poisonous atmosphere. His very poor health had turned him into a ghost who was rarely seen on television, but the authorities could not agree on the name of his replacement. The people, who grew accustomed to these masquerades of elections since the country’s independence, did not vote in April 2014; abstention reached a peak 90 percent, rarely witnessed anywhere else. The people's slap in the face to the regime was resounding, but power makes the one who wields it crazy and blind.

The Algerian leaders demonstrated this five years later; they did not understand that the people had no desire to relive the farce of 2014. Algerians, who were living in miserable conditions, could see that "those above" lived in magnificent mansions, drove around in luxury cars, and regularly took airplanes to travel abroad; they could see that "those ups there" could seek medical attention in top hospitals and clinics in Europe, while they, the people, were directed to Algerian hospitals, which had become more like morgues; they had to send their children to Algerian schools, without any hope of acquiring quality education, while "those above" were sending their children to study in top foreign schools and universities.

Accustomed, since independence, to these masquerades of elections, the people did not vote in April 2014; abstention reached 90 percent, rarely seen anywhere else in the world. The people's slap-in-the-face to the regime was resounding, but power makes the powerful crazy and blind.

On 22 February, the people finally expressed their total rejection of this authority because they felt stripped of their dignity. They did not want to undergo once again the affront of voting for a frame, inside which was a thirty-year old photograph, enthroned on a pedestal before which the servants of the regime came to prostrate themselves.

El-Sissi and Resource Management in Egypt

27-03-2022

How will this confrontation end? No one knows. What we do know is that the army’s Chief of Staff who currently holds the reins of power is terrified of the people in revolt. He is trying to buy peace by offering people the heads of many former officials of the Bouteflika regime. They are about 200 to 300 former ministers, senior officials, crooked businessmen, and others who have been brought to justice. But the initiative of the Chief of Staff has not led to the support of the people whose objective remains the same: to get rid of this regime for good, as the contempt they have for it is as great as the frustrations they have experienced because of it for over twenty years.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabry Zaki

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 20/06/2019