The face is stabbed deep in the eye. Two pairs of shoes shall never be worn. Whoever owned them, she can no longer walk. The Baghdad alley where she played hopscotch was shocked and awed, then house by house emptied of laughter.

The chopped off palms, as the late Iraqi poet Sargon Boulus once said, will not raise a finger towards the murderer tonight. [1] They linger here, motionless, longing for a touch, thrown among a cascading heap of Mesopotamian ruins old and new.

A Past on Fire

Standing here before the ruins of Mahmoud Obaidi’s Fragments, at an exhibition of Latif al-Ani’s photography at New York University’s Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, I see a braid that will never dance after the little girl whose white ribbons are burnt like Iraq’s ashen eons.

The tragedy, embalmed in steel fragments naturally mirroring the nature of instruments of death, and encased in two vitrines, seeps and spews onto the exhibition floor where I stand: an esplanade on the shores of history, where flashbacks ebb and flow as my eyes scan the artist’s installation.

Through Fragments, Obaidi (b. 1966) wants to retrace the “organized chaos” that hurled Iraq into a boomeranging cycle of ruination that hemorrhages an uncontrollable flood of debris.

He recreates the murdered, shattered and stolen remains to stitch Baghdad together piece by piece. Each fragment blasts open a hole in the spectator’s imagination where Iraq, in a scene replayed throughout history ad infinitum, is violated by foreign and homegrown assailants alike.

As Hannah Arendt writes of Walter Benjamin: “for him the size of an object was in an inverse ratio to its significance.”[2] This is how Obaidi’s Fragments should be seen. Like Benjamin, many of us Iraqis roam the ruins to collect the shards from a smoldering past and articulate the unspeakable.

But is the catastrophe, and the past itself, over?

As I stand here, my “smartphone”, this apparatus Giorgio Agamben so loathed he wished all of us be punished and jailed for using, and in whose screen an abyss where the slaughter of Palestinians is a numbing spectacle for war-weary users – vibrates: a message on Telegram![3]

My resignation

17-11-2023

The poseurs of the “Islamic Resistance”, whose cheerleading diaspora “anti-imperialist” scholars wouldn’t want to have a taste of “life” under their dominion, target a base in the city of Erbil. Lacking the morality of a moral fight, since October 7 they have yanked Palestine by the collar.

Soon their guns will be pointed at domestic innocents. In the meantime, the fires in Iraq continue to burn.

What Comes from Heaven

In the presence of Fragments, the first thought that comes to mind is Benjamin’s words on the storm of “progress.” In Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus, Benjamin saw the “angel of history” hurled into a future to which he gives his back, as he eyes a catastrophe rising behind and hurling debris at his feet.[4]

It is a story my ancestors knew well. In the city laments of ancient Mesopotamia, another storm blew from heaven. This time by the god Enlil. This storm, writes John Jacobs, “primarily serves as a metaphor for the enemy invasion and the utter destruction that follows in its wake.”[5]

In the Lament for Ur we read:

“The storm blazing like fire performed its task upon the people. The storm ordered by Enlil in hate, the storm which wears away the Land, covered Ur like a garment, was spread out over it like linen.”[6]

“Again and again in Baghdad’s history,” writes the late Anthony Shadid in Night Draws Near, “the weather has seemed to signal cataclysm.”[7] In 2003, another storm engulfed Baghdad. It was a harbinger of disaster, foreboding, and “a portent of divine will.” Alas, omens come true in Iraq.

In the city laments of ancient Mesopotamia, another storm blew from heaven. This time by the god Enlil. This storm, writes John Jacobs, “primarily serves as a metaphor for the enemy invasion and the utter destruction that follows in its wake.”

On display at the Metropolitan Museum near ISAW’s building is Klee’s Stricken City, in which the German artist etched an emaciated city that is skeletal, desolate, languishing under the threat of a black arrow approaching from heaven like fate. In this eeriness I see the streets where I grew up.

Twenty-one years have passed since the hand of doom brushed over the cities and villages of Iraq, turning lives, palm trees and entire sites of memory to ash, leaving in its wake endless lamentations in many households as black funeral banners dangled outside – to which Iraq do we return today?[8]

I Am All of These Dead Faces

01-09-2023

For a Babylonian, writes Stefan M. Maul, “the past lay before him—it was something he ‘faced.’” As for the future, it was “something he regarded as behind him,” at his back.[9] The Mesopotamian, in his preoccupation with the possibilities contained in the past, walked back into the future.

The development witnessed by Mesopotamian society was seen not as progress, Maul tells us. Rather, a return to unsullied origins and bygone pasts was a “restoration” of utopia, of the glorious and the ideal.[10]

Is there an epoch uninhabited by dumped corpses, hallucinating ghosts, and barbed wire for the Iraqi to return to today?

Morning Walks

Having left the country three years ago to finish my graduate education first at Georgetown University before transitioning to Bard College for further research, I now live in a small village in upstate New York. It is quiet, and so am I.

When I first moved in the summer, I saw a corpse left on the asphalt by the Lutheran church. I pictured myself pulling it to the side of the road by dusk. It was mine, I reckoned. Inheritance, I told myself later. Each Iraqi carries a share of madness – an essential item on the monthly ration card.

Michael, the village’s grocer, is fond of Bob Dylan. He has cherished memories from a distant visit to Lebanon, and tries to keep himself informed on the region’s news. Every time the inferno rages on TV with America’s blessings, Michael reminds me to listen to Bob’s With God on Our Side.

One push of the button and they shot the world wide

And you never ask questions when God's on your side

Looking at the genocidal war in Gaza, I think God has resigned and went into hiding. The Holy Trinity has fallen victim in the Holy Land, mutilated, again and again, by Israel’s AI-assisted weaponry. Children, hungry, in flooded tents, shiver from fear and cold as I write these lines.

In this village, I often walk to the Methodist burial ground near the CVS pharmacy/supermarket – that other cemetery for the living America is fond of. After the day’s first, patiently prepared cup of Arabic coffee, I light a thin cigar and meander past the local bistro towards “Cherry Street.”

The cemetry gate is often left ajar, and I slip in.

Some of the few dozen tombstones are mute, nameless, unable to speak. The names are effaced by the hand of time.[11] Standing here, I think of the mass graves of Iraq, of the nameless Palestinians whose cadavers are piled up in mass graves only to be assailed anew by Israel’s bulldozers.

Is there an epoch uninhabited by dumped corpses, hallucinating ghosts, and barbed wire for the Iraqi to return to today?

The space where I stand, as America itself, closes in and shrinks. I make my way through the empty streets back to the small cottage where I live, and book a coach seat on an Amtrak train bound for New York’s Penn Station. I needed to visit Iraq through Latif al-Ani’s photography and breathe.

Baghdad-New York

Once in New York City, however, I am assailed from every lamppost with stickers screaming "FREE GAZA FROM HAMAS." This country is always on heat. There always exists a band of enemies to be fought somewhere overseas.

Walking on Park Avenue, a digital billboard hung on the back alley of the Helmsley building greets me with a waving Israeli flag and a boisterous proclamation: We Stand in Steadfast Solidarity with Them. In Palestine there exist no innocents, only nonbeings to be fought, as in Iraq, With God on Our side!

New York, a city that has always lit a fire in me for the past two years, wears an unfamiliar mask this time. I feel nothing for her. I make my way to the Upper East Side to ISAW building. Once at the exhibition venue, I find in al-Ani’s photographs an invitation to grieve.

The Insult

03-07-2023

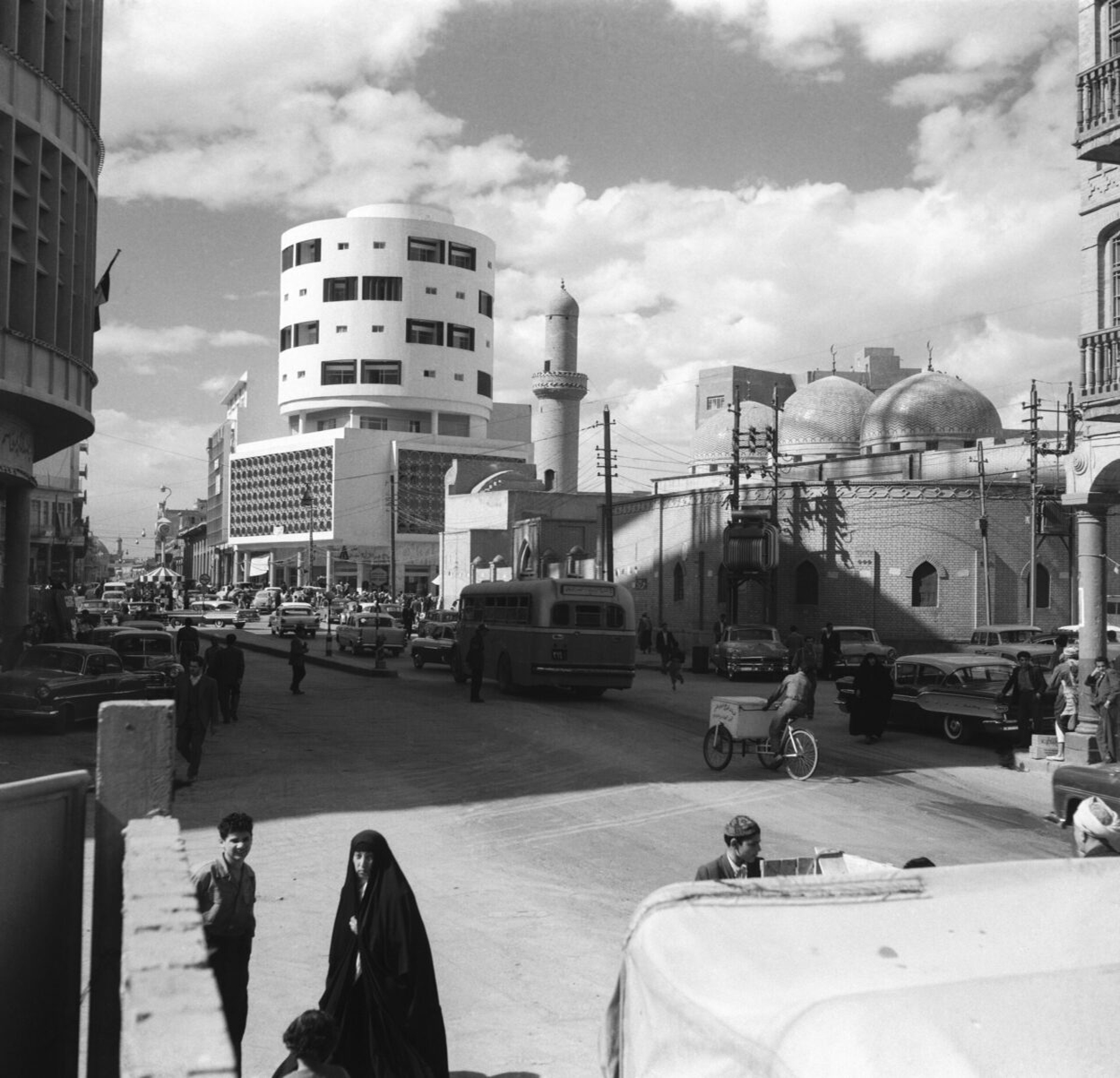

In the black and white images decorating the walls at ISAW are slivers of a seemingly less-turbulent time: the modernist residence of architect Hisham Munir in an ordinary afternoon; the minaret of Samarra rising high in the distance; and portraits of tourists against a sun-washed background.

With a Rolleiflex strapped around his neck, that double-lensed “friend” with which he wished to remain discreet, al-Ani’s attentive eye observed the eventful and the mundane, stopping time to document the life of royals and plebeians with equal interest in (and attention to) their milieu.

Through al-Ani’s photographs I walk up the minaret of Samarra with my father, and travel with my extended family on a battered Coaster bus to the ruins of Ctesiphon – images of my childhood flit by on the walls of memory from a life lived, as Sinan Antoon puts it, in a recess between two wars.

The aerial shots of Jewad Salim’s Freedom Monument at al-Tahrir square invite me to revisit distant afternoons where the fourteen friezes, mounted on a monumental banner by architect Rifat Chadirji, loomed among slender palm trees greeting incoming traffic from a bridge across the Tigris River.

In one of these afternoons, I was tear gassed, thrown unconscious on the sidewalk. In October 2019, the state and its militiamen mowed down hundreds underneath Salim’s monument and at the neck of al-Jumhuriyah Bridge. I wonder if the protesters who rushed to my aid made it alive.

Image and Politics

Al-Ani (1932-2021) is the celebrated father of Iraqi photography. His colored and black and white photographs appeared in the Iraq Petroleum Company’s Ahl al-Naft (People of Oil) – a publication that, inter alia, featured photographs rationalizing the modernizing project of both IPC and the state.

In Kirkuk, for instance, where the state and IPC hoped to counter communist influence through urban development, Arbella Bet-Shlimon writes that Ahl al-Naft was issued to “generate positive publicity” among the locals, with the housing schemes having “little positive impact on the poor.”[12]

The celebrated “golden age” of modernity that al-Ani photographed was also a glamorous veneer behind which, as Hanna Batatu, Mohammed Mahdi al-Jawahiri and Sargon Boulus write, communists and students were oppressed, the press censored, and communities impoverished.[13]

As Mona Damluji puts it: “these images only bring us into the city as far as the oil company and state would want us to see; and so, the darker side of development remains hidden from view.”

Walking on Park Avenue, a digital billboard hung on the back alley of the Helmsley building greets me with a waving Israeli flag and a boisterous proclamation: We Stand in Steadfast Solidarity with Them. In Palestine there exist no innocents, only nonbeings to be fought, as in Iraq, With God on Our side!

Baghdad itself suffered the erasure of entire quarters for main streets such as al-Rashid, al-Khulafa and Haifa to violently course through. As seen elsewhere in the Arabian Peninsula, existing urban fabric, Caecilia Pieri writes, was obliterated.[14] Bourgeois suburbs spread as old quarters decayed.

I think of Baghdad’s wounds as I converse with al-Ani’s photos, which open up like passages through which I travel in time and wander the canals of my hometown beyond the dictatorial borders of the frame.

Al-Ani would later head the official Iraqi News Agency. With the rise of the Ba`ath Party to power, in the 1970s he felt his work was serving as propaganda for a state crafted mono-culture. Eventually, his uncle was executed, his Rolleiflex died, and he quit photography.

War

In 2003, much of his 200,000 negatives, along with thousands of Iraq’s archival documents and artworks, were lost in the bedlam as the hoofs of America’s war-machine trampled over Iraq, setting afire the “present” and the “past” in a barbaric invasion akin to ancient Iraq’s mythical disasters.

In Iraq’s Invisible Beauty, a Jurgen Buedts and Sahim Khalifa film in which the latter, blabbering ad nauseam in al-Ani’s ears, drives the photographer in his two-tone Buick on a cross-country trip to the sites of some the most iconic shots – al-Ani is appalled at the death of places and the birth of chaos.

“Iraq is the only country in the world whose past is better than its present,” al-Ani says solemnly, as the camera follows him on al-Rashid, outside the historic Mirjan Mosque, which converses with the adjacent cylindrical Burj Aboud, a modernist tower by architects Chadirji and Abdullah Ihsan Kamil.

An eloquent euphemism for war’s afterlives is seen in Nadine Hattom’s Shadows, an installation accompanying al-Ani’s images in which the artist edits out the figures of US troops from open source images taken by the occupiers themselves. Their shadows remain a haunting presence.

Somehow the curators’ discourse here omits another ghastly presence, as visitors are not told that the archaeological site of ancient Babylon was itself occupied and desecrated by contractors, who dug trenches and erected a base on site.

A Mythical Iraq

Also missing are the faces of ordinary Iraqis. Besides portraits of al-Ani, the visitor encounters a blind musician entertaining gullible white tourists in traditional costumes at Ctesiphon with his rababa – a stereotypical rendering that, even if inadvertently, emphasizes nature and folklore.[15]

Despite striving to show the “beauty” of Iraq, such images are a reminder of the stakes of lending one’s talent to IPC’s media apparatus – a period during the pro-British monarchical rule with which an “apolitical” al-Ani was enamored, and is seen reminiscing about in the film Iraq’s Invisible Beauty.

Moving through the two separate rooms of the exhibition, the visitor encounters more white folks than locals. The presence of white tourists at Taq Kusra is thus accentuated. Despite the discourse on Orientalism, it becomes as intrusive now as it was then, as invasive as the troops’ shadows.

Recent images of other type of tourists offer their own host of mythologies. In GQ Magazine, an interview with Narcy (the moniker of a rapper largely unknown in Iraq) about his “homecoming” “adventure” offers a befitting example with its own emphasis on the folklorish and the ancient.

Peppered with the artist’s prosaic rhymes, the interview’s images show a land seemingly deserted, one from which not only people are vacated (only in the diaspora do Iraqis who speak exist), at best reduced to faraway dots in the background, but history itself, as if a fugitive, is expelled.

In an alibi for unity, one image shows the artist anchored on his protector’s shoulder. The soldier turns his back to the camera, exactly how tormented youth like to see: going away. Behind is Isma`il al-Turk’s turquoise Marty’s Monument, reduced to an aesthetic object and emptied out of history.

The artist, as the photographer, seems not interested that Nusb al-Shahid is a monument for death, erected for the hundreds of thousands of soldiers “martyred” during a devastating war with Iran. Still, with shoes from Ferragamo, a triumphant Narcy storms the picturesque like a liberator.

Narcy is also romantic. He loves sunsets by the Tigris and plays with its waters without having to roll up his sleeves. The medical waste, the flowing sewage, the seasonal drought, all merit no mention here. He is unaware, perhaps, of the slow-death of the Tigris and Euphrates.

As the late Roland Barthes would say: “This tourist is a wonderful alibi here: thanks to him, one can look without understanding, travel without taking any interest in political realities.”[16] Leisurely, the Tigris flows unbothered. The reader needs not know what happens on its two banks.

- Sargon Boulus, Azma Ukhra Li Kalb El-Kabila (Cologne-Baghdad: Al-Kamel Verlog, 2008), 216. ↑

- Walter Benjamin, Harry Zohn, and Hannah Arendt, Illuminations: Essays and Reflections (Boston ; New York: Mariner Books, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019). ↑

- Giorgio Agamben, “What Is an Apparatus?” And Other Essays, Meridian, Crossing Aesthetics (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 2009), 16. ↑

- Benjamin, Zohn, and Arendt, Illuminations, 201. ↑

- John Jacobs, “The City Lament Genre in the Ancient Near East,” in The Fall of Cities in the Mediterranean: Commemoration in Literature, Folk-Song, and Liturgy, ed. Mary R. Bachvarova, Dorota Dutsch, and Ann Suter (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 24. ↑

- Jacobs, 28. ↑

- Anthony Shadid, Night Draws near: Iraq’s People in the Shadow of America’s War, 1st Picador ed (New York, N.Y: Picador, 2006), 72. ↑

- I think with Adorno’s words on the American landscape as I write these lines: Theodor W. Adorno and E. F. N. Jephcott, Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life, Verso 2020 edition, Radical Thinkers (London ; New York: Verso, 2020), 52. ↑

- Stefan M. Maul, “1. Walking Backwards into the Future: The Conception of Time in the Ancient Near East,” in Given World and Time, ed. Tyrus Miller (Central European University Press, 2008), 15, https://doi.org/10.1515/9786155211591-003. ↑

- Maul, 20–21. ↑

- I write this line with Boulus’s words in mind: Boulus, Azma Ukhra Li Kalb El-Kabila, 98. ↑

- Arbella Bet-Shlimon, City of Black Gold: Oil, Ethnicity, and the Making of Modern Kirkuk (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2019), 126–34. ↑

- Hanna Batatu, The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary Movements of Iraq: A Study of Iraq’s Old Landed and Commercial Classes and of Its Communists, Bacthists, and Free Officers (Princeton, New Jersey: PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 1978); Muhammad Al-Jawahiri, Thikrayati: Al-Juz` al-Thani, 1st ed. (Damascus: Dar al-Rafidain, 1988). ↑

- Caecilia Pieri, “Sites of Conflict: Baghdad’s Suspended Modernities versus a Fragmented Reality,” in Urban Design in the Arab World (Routledge, 2015), 204. ↑

- In this section I think with Barthes: Roland Barthes, Mythologies, trans. Richard Howard and Annette Lavers, First American paperback edition (New York: Hill and Wang, a division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013). ↑

- Barthes, 146. ↑