By what standard of morality can the violence used by a slave to break his chains be considered the same as the violence of a slave maste?

— Walter Rodney

Following Hamas’s October 7 attacks on Israel that caused more than 1,200 fatalities, there was a barrage of injunctions from Western mainstream media, politicians, and pundits insisting that anybody wishing to express an opinion on the events and the ensuing Israeli war crimes and genocide in Gaza, first denounce Hamas before expressing any other view. The failure to explicitly do so or any attempt to put events in their historical context or emphasize the root causes of the conflict were interpreted as condoning Hamas’s actions (that the speaker was a Hamas sympathizer) and conflated with antisemitism.

It was as if the history of what is called the Palestinian-Israeli conflict started on October 7 and not with the 1917 Balfour Declaration that saw the colonial British government announce its support for the establishment of a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine. That announcement culminated in what Palestinians and Arabs call the Nakba (the Catastrophe) in 1948, concomitant with the founding of the state of Israel through the widespread ethnic cleansing, massacres, and the displacements of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians. More wars followed, more violence, more killings, and more occupation of new territories. This led to still more displacements, more illegal settlements, and more bombings, which cost the lives of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians and forced millions more to live as refugees. I will not dwell on this history as numerous wonderful resources have done so brilliantly. Rather, my purpose here is to draw some parallels from the history of the Algerian anticolonial struggle to show the vacuity, shortsightedness, and injustice of denouncing the violence of the oppressed/colonized and oppressor/colonizer in equal terms. The moral dilemmas, debates on violence, and disagreements around how oppressed or colonized people should resist, and what they may or may not do, are not new.

When I think about Palestine, I cannot help but draw parallels with the case of my home country Algeria during the colonial era (1830-1962). It is no coincidence that the Algerian popular and working classes strongly support the Palestinian cause as both countries experienced/experience violent, racist settler-colonialism. To understand why, it is worth visiting Frantz Fanon’s writings and analyses about what he called “revolutionary violence” in his masterpiece The Wretched of the Earth, which he wrote based on his experiences in Algeria and West Africa in the 1950s and early 1960s. The Wretched of the Earth is a canonical text about the anticolonial struggle and served as a kind of bible for liberation struggles from Algeria to Guinea-Bissau, South Africa, Palestine, and the Black liberation movement in the US.

Fanon thoroughly described the mechanisms of violence put in place by colonialism to subjugate oppressed people. “Colonialism is not a thinking machine, nor a body endowed with reasoning faculties. It is violence in its natural state, and it will only yield when confronted with greater violence,” he wrote. According to Fanon, the colonial world is a Manichean world, which, taken to its logical conclusion, “dehumanizes the native, or to speak plainly it turns him into an animal.” For him, “National liberation, national renaissance, the restoration of nationhood to the people, commonwealth: whatever may be the headings used or the new formulas introduced, decolonization is always a violent phenomenon.”

The Algerian independence struggle against the French colonialists was among the most inspiring anti-imperialist revolutions in the 20th century. Part of the decolonization wave that began after World War II (in India, China, Cuba, Vietnam, and many African countries), the Bandung Conference declared these movements to be part of the “awakening of the South”—a South that has been subjected for decades (in some cases more than a century) to imperialist domination.

Following the November 1, 1954 declaration of war in Algeria, merciless atrocities were committed by both sides (1.5 million deaths with millions more displaced on the Algerian side, and tens of thousands dead on the French side). The National Liberation Front (FLN) leadership had a realistic appraisal of the military balance of power, which tilted heavily in favor of France, which then had the fourth-largest army in the world. The FLN strategy was inspired by the Vietnamese nationalist leader Ho Chi Minh’s dictum “For every nine of us killed we will kill one—in the end you will leave.” The FLN wanted to create a climate of violence and insecurity that would ultimately prove intolerable for the French, internationalize the conflict, and bring Algeria’s struggle to the attention of the world.

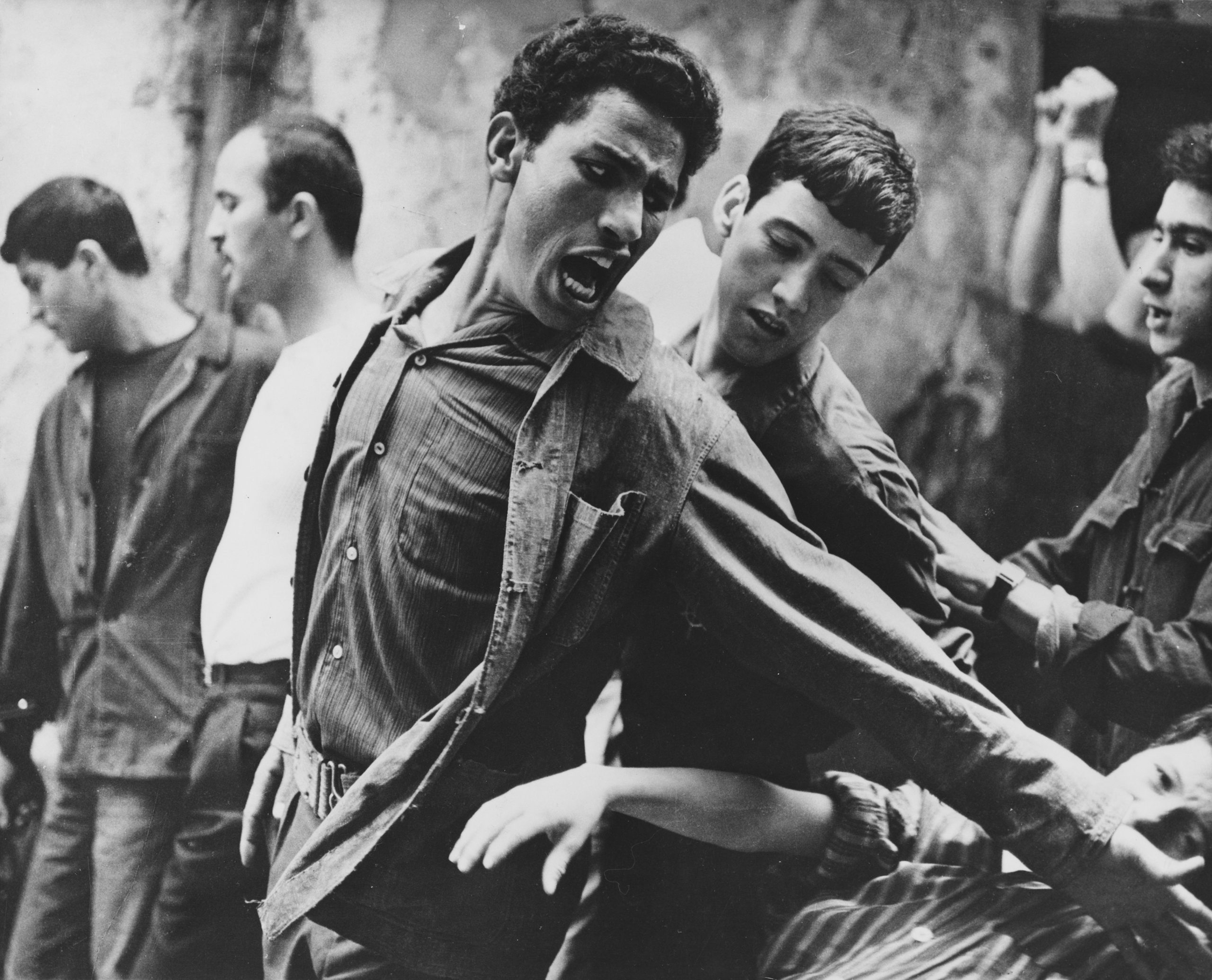

Following this logic, Abane Ramdane and Larbi Ben M’hidi decided to take the guerilla warfare to urban areas and launch the Battle of Algiers in September 1956. There is perhaps no better way to appreciate this key and dramatic moment of sacrifice than the classic 1966 realist film of Gillo Pontecorvo: The Battle of Algiers. In the film, there is a dramatic moment when Colonel Mathieu, a thin disguise for the real-life General Massu, leads the captured FLN leader Larbi Ben M’Hidi into a press conference at which a journalist questions the morality of hiding bombs in women’s shopping baskets. “Don’t you think it is a bit cowardly to use women’s baskets and handbags to carry explosive devices that kill so many people?” The reporter asks. Ben M’hidi replies: “And doesn’t it seem to you even more cowardly to drop napalm bombs on defenseless villages, so that there are a thousand times more innocent victims? Give us your bombers, and you can have our baskets.”

Through widespread favorable coverage of the Algerian revolution in the African-American press, many local screenings of The Battle of Algiers, as well as Fanon’s writings, Algeria came to hold a seminal place in the iconography, rhetoric, and ideology of key branches of the African-American civil rights movement, which came to see its struggle as connected to the struggles of African nations for independence.

After visiting Algeria in 1964 and the Casbah, the site of the Battle of Algiers against the French in 1956-1957, Malcom X declared:

The same conditions that prevailed in Algeria that forced the people, the noble people of Algeria, to resort eventually to the terrorist-type tactics that were necessary to get the monkey off their backs, those same conditions prevail today in America in every Negro community.

A few months later, in 1965, he went on to say:

I don’t favor violence. If we could bring about recognition and respect of our people by peaceful means, well and good. Everybody would like to reach his objectives peacefully. But I’m also a realist. The only people in this country who are asked to be nonviolent are black people.

And upon hearing of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968, the Black Panther Party leader Eldridge Cleaver proclaimed:

The war has begun. The violent phase of the black liberation struggle is here, and it will spread. From that shot, from that blood. America will be painted red. Dead bodies will litter the streets and the scenes will be reminiscent of the disgusting, terrifying, and nightmarish news reports coming out of Algeria during the height of the general violence right before the final breakdown of the French colonial regime.

We too must challenge the victim-blaming narrative that fixates on Palestinians as imperfect victims, which in the words of the American-Palestinian scholar Noura Erakat, amounts to an “absolution of, and complicity with, Israel’s colonial domination.” In choosing to highlight Palestinian violence, our message to them “is not that they must resist more peacefully but that they cannot resist Israeli occupation and aggression at all.”

Denouncing and singling out the violence of the oppressed and colonized is not just immoral, but racist. Colonized people have the right to resist with any means necessary, especially when all political and peaceful avenues have been stymied or obstructed. Over the past 75 years, every Palestinian attempt to negotiate a peace deal has been rebuffed and undermined. Every non-violent means has been blocked, including the “March of Return” endorsed by Hamas in 2018 (savagely repressed, with more than 200 people killed and tens of thousands wounded and maimed) as well as the international Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) campaign, which has been made illegal in several Western countries under pressure from the Zionist lobby.

Amid a barbaric, colonial occupation, and Apartheid conditions, it would be fitting for any talk about justice and accountability for violence against civilians to start with the oppressor. As Fanon’s rationality of revolt and rebellion puts it, the oppressed revolt because they simply can’t breathe.

My resignation

17-11-2023

Choosing to focus on denouncing Palestinian violence is akin to asking them to passively accept their fate—to die quietly and not resist. Instead, let us focus on an immediate ceasefire, halting the unfolding second Nakba, and ending the siege and the Occupation, while showing our solidarity with Palestinians in their struggle for freedom, justice, and self-determination.

Palestinian lives matter!