This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

The shelter sits beneath the garden, and the grapevine arbor stretches over the wall, as though it sprung from an ancient place beyond. Its branches cascade onto the garden's soil which has not seen green grass in a long while, ever since my father decided to build a bunker underneath it to shelter us from the American warplanes. The aircrafts would often materialize, as if from thin air, over our cities and release precision-guided bombs onto us. After all, this had happened several times before, on the fortified civilian shelter of Al-Amiriyah and on Laila Al-Attar’s home, so why should we be an exception?

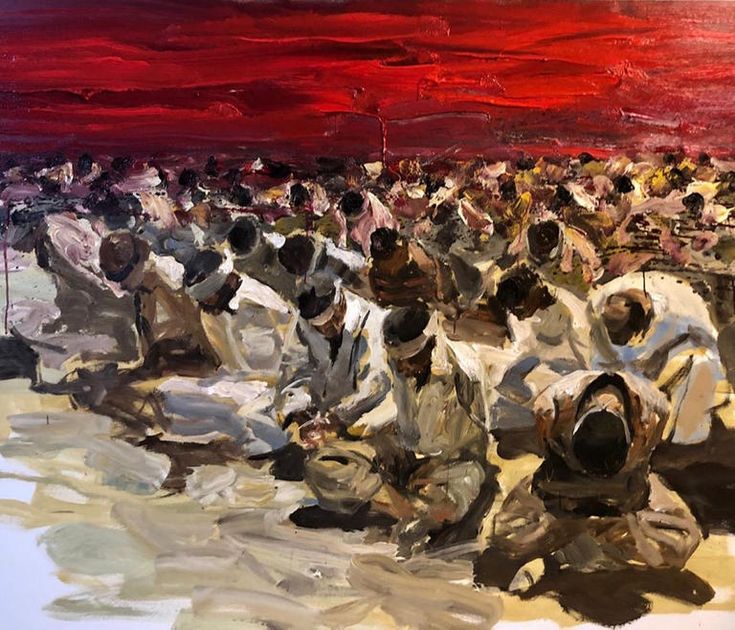

Dawn usually brings along a gentle breeze, but on that particular day, it carried the scent of death – not the kind that merely kills but that which crushes bodies to a pulp and obliterates them to dust until nothing remains. It was reported in the news that the dead numbered 408. In reality, that was just the number of bodies found, while others perished without a trace. All that was left of them was their final image in the memory of the survivors: They awoke from their sleep and proceeded to perform ablution as they prepared for the Fajr prayer. They were anxious and afraid as they sought refuge within the concrete walls of the Al-Amiriyah shelter, clinging to dear life. But all their efforts were in vain.

It happened at dawn on Tuesday, February 13, 1991. Iraqis had no idea that two F-117 Nighthawks were bringing them death wrapped in two guided bombs, the first of which penetrated a 1.5-meter thick ceiling, while the second one descended on the terrified bodies in the shelter, exploded, and tore them apart. 261 women, 52 children, and 95 men were discovered lifeless. There were others whose remains were never found. The explosion had incinerated their bodies.

People were talking with trembling voices about the massacre in Al-Amiriyah. Terrible photographs circulated, and the faces of people in Baghdad wore an unmistakable expression of terror. The aftermath of the massacre filled my father with unease and fear as he grappled to find ways to protect us, ways that neither he nor the state could provide. He dug an impromptu shelter for us in the garden, knowing it would not withstand much. He had witnessed the horror that had unfolded in Al-Amiriyah, but what else could an Iraqi father do to shield his family from the US missiles and bombs? He didn't want to leave his home, so he dug a trench.

The grass in our garden withered away, and the grapevine arbor saw its final demise. We turned the latter into our own wooden monkey bars, and we broke off its desiccated branches to smoke like cigarettes. Our father, in true Iraqi paternal tradition, responded sternly upon discovering our antics. He uprooted the arbor, scolded us, and punished us with falqa (beating the soles of our feet with a stick). He also warned use that the shelter was no playground, and that we were only to enter it upon hearing the sirens wailing in the city’s skies.

That was when the sky became an object of obsession for us Iraqis. It was the final barrier between us and the US Army. They were over there, in their distant bases, but we remained in close proximity to them, should they choose to take to the sky - their means and their route. On January 18, 1991, we realized the significance of that vessel. In a single night, 100 Tomahawk missiles, never before used in history, rained upon us from the heavens. 1,300 air raids were carried out in our skies, and the bombing continued for 42 harrowing days. Death struck our cities like cataclysmic thunderbolts.

The French newspaper Le Figaro quoted its Baghdad correspondent, Remy Favre, describing that fateful night: “Fires caught fire in the sky of Baghdad, and the camouflaged air defenses on hundreds of surfaces began firing, the American F-15 planes struck Iraq on the head (…), during which the sky [of Baghdad] was torn apart.” It was a time when weaponry held sway, and the United States was keen on telling the people of the world that it was indeed ‘the world’s superpower.’

It appeared that waging a war on a weak and vulnerable nation was the US’s way of delivering a conclusive blow to the Soviet Union’s ailing body, hastening its inevitable dissolution, and none was weaker than Iraq. It was a country ruled by a dictator who believed in Arabism as an Arab Bedouin might believe in the supremacy of his own small tribe. And while the dictator spoke in a televised speech about the infidels, the descendants of the prophets, the hornets’ nests, and jihad, 2250 fighter planes were dropping bombs upon the nation he ruled, in the fiercest, most enduring aerial warfare in human history.

The numbers say that 200,000 civilians and an equal number of soldiers, children of these civilians, lost their lives in the war. But nobody keeps track of the number of the scared in times of war - those who may have cheated death but still bore witness to it. We were among those forsaken masses, digging trenches in our garden, razing our grass and sacrificing our grapevine to survive. And now, we find ourselves telling the story of what happened. The numbers say that 200,000 civilians and an equal number of soldiers; children of these civilians, lost their lives in that war. But nobody keeps track of the number of the scared in times of war - those who may have cheated death but still bore witness to it. We were one of those left in the dark corners, digging trenches in our garden, razing our grass and sacrificing our grapevines to survive. And now, we find ourselves telling the story of what had happened…

A war that started long before 2003

The war on Iraq began long before 2003. There was ample time for spreading hunger and fear in the country, while Iraqis' fascination with the sky had waned as their gazes lowered to the ground in defeat. Thirteen years of siege could tame a pack of wild beasts, and the hearts of Iraqis were each a beating cage wherein fear, violence, poverty, silence, disease, and ignorance were growing, restless beasts. When the second round of war commenced, all the wild beasts were unleashed, and they have been roaming and multiplying ever since.

Around the time Saddam Hussein met his fate on the gallows, I had taken up the company of Sweileh, our village’s “madman” - and sage. We often found ourselves perched atop the water pipe that served as the lifeline of our village and snaked through the village alleys. Sweileh possessed an insatiable appetite for news broadcasts, and he particularly enjoyed imitating the newscaster. He would somberly recount the death tolls of explosive cars, and just as swiftly, he'd become the Minister of Defense incarnate, Sultan Hashem Ahmed, beseeching then-Secretary-General of the United Nations, Kofi Annan, to orchestrate the withdrawal of the US military from Iraq and facilitate the terms of Israel's quick surrender, before President Saddam Hussein unleashed the rest of his missiles against it.

Law No.111 in Iraq: Speaking Up is a Crime!

31-03-2023

Sweileh would then sternly warn Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and his followers, threatening that any bloodshed among the police or army ranks who hailed from ancestral clans would not be tolerated. These figures, lacking even the most basic amenities such as electricity and water, were to be respected. Sweileh believed the elders of the community bore the responsibility of convening to solve any problems and expel Al-Shawka family from the community's embrace for their repeated transgressions, thievery, car-napping, and thuggery against unsuspecting travelers along the international highways.

The chaos in the city was not very different from the haze in Sweileh’s mind. Everything seemed to be spiraling out of control. Powerful clans seized whatever state property they got their hands (and weapons) on. Food stores, banks, ammunition storages, fuel and oil depots, hospitals, schools, universities, and the remaining state institutions were looted, and civilians were cruising the streets in government-owned vehicles. The village we had moved to looked like a military barracks due to the large number of ZIL and GMC military vehicles that wandered its streets. The pious believers who did not miss a single Friday sermon used to gather at night to steal the iron PRC fence that ran along the international road with Jordan to build their new houses from the barriers they had dismantled from both sides of that highway.

However, while chaos was rampant, not everyone participated in the madness, but we all watched it happen. The once terrifying iron state had vanished, and the long-repressed instincts were now uncontrollably on the loose. Merely an hour away from our house, a civil war had erupted in Baghdad between Sunnis and Shiites. Funerals arrived in our village, and all we could do was dig up graves and sprinkle them with rose water.

{And whoever saves a life, it will be as if they saved all of humanity} (1)

“Decadence is more dangerous than the occupation,” the honourable sheikh always repeated, as if he could foretell what was about to happen. The librarian of the Great Mosque, Sheikh Khalil Ibrahim al-Kubaisi, chose solitude over the festival of madness outside, but he never shut the library’s doors in the face of those in need. Many came to him seeking advice and asking for his blessings. They had been through a lot in life and had come to the library to tell their stories. I practically lived at the library, and so, sometimes, I heard their tales.

The war on Iraq began long before 2003. There was ample time for spreading hunger and fear in the country, while Iraqis’ fascination with the sky waned as their gazes lowered to the ground in defeat. After thirteen years of siege, fear, violence, poverty, disease, and ignorance were growing beasts. When the second round of war commenced, they were all unleashed.

In a remote corner of the library, a drawer bore the inscription ‘Private Research’. It was opened once or twice a week by an individual who holds its key; a tall, deliberate man who moved in a soldier-like manner. He always entered the library in a white dishdasha, and occasionally, he would be holding a string of prayer beads in his hand.

More often than not, he would sit alone with Sheikh Khalil, exchanging hushed dialogues, pausing when someone entered the room, but I overheard some of the Sheikh’s guidance. They talked about jihad, the US occupation, the government, and all that was happening, from an Islamic standpoint. In the Sheikh’s opinion, what was transpiring was a kind of “collective madness,” advocating for the pursuit of individual survival. He believed politics was impure and that religious clerics were some of the most dangerous groups in society because their influence, eloquence, and sanctity rendered them both potent and vulnerable to “spiritual afflictions.”

He said that a very slim fraction of this group had learned to quell their vanity and dedicate themselves to God, people, and their own spiritual betterment. He called vanity “the ego” or “master of the self.” In his eyes, the ego was the worst of our problems in Iraq.

I found out later that the man who came in for the ‘Private Research’ drawer was a ‘mujahid’ in Afghanistan during the days of jihad against the Soviet Union. He had fought with Al-Qaeda, and when the United States invaded Iraq, he became a Prince within the organization. Later, he left the group, or they may have expelled him. That makes no difference, yet an interesting distinction lies in the reason behind that rift.

During one of Al-Qaeda's operations against the US army in the city of Al-Ramadi, they captured a Sudanese translator who worked for the US army. When the Prince asked him why he did it, the translator's tearful response was “poverty.” This prompted the Prince to intervene for the man's safety. He gifted him a wristwatch and made arrangements for the translator's relocation to Baghdad, with the condition that he would return to Sudan.

According to Al-Qaeda's jihadist ideology, the translator was to be eliminated, a directive they were prepared to carry out. However, it was this Prince's sense of basic human compassion and Arab solidarity that transcended religious allegiance. This, in particular, was the reason for the parting of ways between the Prince and Al-Qaeda. It marked the primary distinction between the armed groups known as the 'resistance' against the US army and the terrorizing ways of Al-Qaeda.

Al-Qaeda fighters consider themselves ‘jihadists,’ dedicated to the cause of God. To them, participating in a holy war is an unequivocal obligation, and martyrdom represents "one of the two favorable outcomes" of combat undertaken in the name of Allah. In contrast, the civilian casualties resulting from their actions are perceived as collateral damage, individuals whose ultimate judgment rests with Allah, contingent upon their intentions. With this moral quandary seemingly resolved, Al-Qaeda proceeded to engage in street battles and the deployment of booby-trapped cars and explosive devices within residential neighborhoods. This approach was facilitated by the relative ease of targeting US soldiers in narrow alleys, where the soldiers lacked familiarity with the cities and their inhabitants.

The ‘resistance,’ however, primarily consisted of individuals who hail from clans and the Iraqi army that was disbanded by American administrator Paul Bremer. Its fighters’ perspective on the conflict clearly diverges from that of Al-Qaeda. To them, the fight is directed solely against the occupier, with the goal of liberating Iraq from the US troops. In the ideology of the Al-Qaeda, this stance is deemed a departure from Islam and a betrayal of fellow Muslims, categorized as ‘riddah’ - an act of apostasy that warrants execution.

The US had miscalculated the cost of its war on Iraq, which significantly outweighed the gains from oil and arms. Iraq slipped from the American grasp like a fish from a fisherman's hold, only to be captured by another, tighter grip – that of Iran. The latter’s familiarity with Iraq affords it a keen understanding of Iraqi vulnerabilities.

In his book entitled “Why Do You Kill, Zaid?” German journalist and politician Jürgen Todenhöfer tells a story that truly illuminates the distinctions between resistance operations against the US occupation and Al-Qaeda's jihad. The story revolves around Zaid, who was assigned the task of detonating an explosive device in a US army convoy on Street 20 in the city of Al-Ramadi. Zaid's role was to press the detonation button as Humvees, filled with American soldiers, passed by. However, as the military convoy advanced over the explosive canister, Zaid discerned an elderly man in close proximity to the envoy, and thus refrained from triggering the detonation. At least four US occupying soldiers survived because a civilian had to be spared death in that operation. Todenhöfer says that despite the fact that the operation did not proceed, the resistance fighters warmly embraced Zaid and commended his choice to prioritize saving the life of the elderly Iraqi man.

The writer delves into the United States’ hostility and the Western notion of a war against terror. He attempts to formulate a new definition of the term ‘terrorist’ within one of his book’s chapters titled ‘In Search of the Truth.’ He then raises the question (while assuring his readers that he does not intend to draw comparisons): If Al-Qaeda's terrorist operations have resulted in the deaths of 5,000 individuals, who then bears responsibility for the demise of 70 million lives during World War I and II? He subsequently proposes a series of questions, unraveling the West's double standards in justifying wars and evaluating violence between the ‘Western and non-Western worlds.’

Everything seemed to be spiraling out of control. Powerful clans seized whatever state property they got their hands on. Food stores, banks, ammunition storages, fuel and oil depots, hospitals, schools, universities, and the remaining the state institutions were looted, and civilians were cruising the streets in government-owned vehicles.

Todenhöfer recounts the story of Zeid and his tragic loss of both his brothers to US army snipers. The narrative reveals how the ravages of war prompted a 22-year-old young man to shoulder arms and resist the occupying forces that claimed the lives of numerous young people and destroyed Iraqi cities under the pretext of liberating them from a dictatorial regime. Ironically, the American approach, marked by high costs that persist to this day, proved to be even more detrimental than the dictatorship itself.

More stray bullets than birds in the sky

It wasn’t always possible to venture into the streets of the city. Sometimes, the long days of curfew dragged on and the street battles showed no signs of subsiding. There were more stray bullets in our sky than there were birds; there were more dead bodies in the streets than pedestrians. The explosive devices planted on sidewalks outnumbered the benches, turning a regular walk in the city into a risky adventure. Going to the market posed an even greater risk, especially since it meant entering the heart of the old city, where the US army had transformed the local government headquarters into a military base. Within a square kilometer of their fortress, they planted their surveillance cameras, snipers, and barricades. Meanwhile, the rest of the city descended into utter chaos.

Within that enclosed square kilometer, the US army conducted its dirty dealings and illicit activities. They managed Anbar Province in a manner reminiscent of how Hollywood films depicted their management of Third World countries: specific individuals—often the clans’ sheikhs, local leaders, and corrupt thieves—were handed millions of dollars in exchange for their cooperation. Those agents recruited followers who were tasked with safeguarding the US supply routes, as these were the primary concerns of the US army during that period. These practices fostered an environment that not only encouraged but also propagated corruption, which subsequently permeated Iraqi political life to an extent still manifest in the present day.

Al-Qaeda fighters consider themselves ‘jihadists,’ dedicated to the cause of God in an unequivocal obligation. The civilian casualties resulting from their actions are perceived as collateral damage whose ultimate judgment rests with Allah. With this moral quandary seemingly resolved, Al-Qaeda proceeded to engage in street battles and the deployment of booby-trapped cars and explosive devices within residential neighborhoods.

In 2008, the State Audit and Administrative Control Bureau in Iraq issued its annual report, which stated: “In 2007, the US army in Anbar Province provided an amount of $614,400 to the director of the sewage department in the city of Al-Ramadi for the purpose of implementing projects pertaining to the department. However, there is no information available from the accounting department as to how this amount was expended. The Bureau has requested an investigation into the disappearance of this fund.”

The department's director was just one of hundreds of corrupt officials, employees, and tribal sheikhs who joined the Islamic Party in seizing contracts awarded by the US military to its collaborators. Some of the initial privileges shared with the Islamic Party in 2007, apart from power and official positions, were an additional $70 million added to the budget of the Anbar Province, $50 million in compensation allocations, and the creation of 6,000 local jobs. These jobs were distributed within the sheikhs' circles to buy the loyalty of the tribal masses.

This corrupt and hostile environment created fertile ground for the proliferation of extremism in all its forms: religious, tribal, and partisan. As this atmosphere continues to grow rampant, the state and its laws retreat to the background, no longer capable of holding any real effect or sway. To every means of the law and the state, an in-kind alternative is created. Against the law stands faith – be it in religion, sect, or tribe- and, indeed, faith prevails. Against the state’s armaments, or the so-called tools of ‘legitimate violence,’ are the weapons of the clans, armed groups, and militias, and these weapons also prevail as more powerful and effective. This characterizes all Iraqi contexts post-2003. In Sunni environments, as in Shiite environments, this scenario has unfolded, with subtle differences only in its aesthetics, mannerisms, dialects, and rituals.

Right from the beginning, the US military and the Washington administration treated the Iraqis as the British had treated the Indians. Their failure to grasp the distinct contexts and timings of each occupation only exacerbated the situation. What compounded the Americans' lack of understanding was the emergence of alternative parties and figures from the Baathist era, who came to take control of a country and a people now on the loose.

Washington has established a new system based on ‘muhasasa,’ a quota-based political system through which thieving factions, empowered by arms and corrupt money, were able to take over the state and its institutions. This system was consecrated through the methods of Paul Bremer, the de facto American figurehead in Iraq, as leader of the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA). Bremer handpicked CPA members under the presumption that each of them should be a representative of either the Shiites, the Kurds, the Sunnis, or any among the numerous minorities in Iraq – a nation about which Bremer lacked any real understanding.

Bremer was once described by Kurdish leader Masoud Barzani as an “arrogant man, ignorant about the region.” Barzani recounted a meeting with Bremer during which the latter asserted that he represented “international legitimacy,” and that “the Security Council has decided that this is an occupation, which is an ugly word that you have to get used to.” Bremer promised to form a committee of Kurdish advisors, but cautioned them “not to expect that their every suggestion will be approved.”

What the numbers say

The US had miscalculated the cost of its occupation of Iraq, which significantly outweighed the gains from oil and arms. Iraq slipped from the American grasp like a fish from a fisherman's hold, only to be captured by another tighter grip – that of Iran. The latter's advantage lies in its familiarity with Iraqis, which affords it a keen understanding of Iraqi vulnerabilities. Former Iraqi Minister of the Interior, Falah al-Naqib, had even accused Iran of bombing the shrines of the two Al-Askari Imams, highly revered by the Shiites, located in the Sunni city of Samarra. He also claimed that Iran was preparing a $200 million operation to transfer the remains of Imam Ali al-Hadi from Samarra to Iran.

Right from the outset, the US treated the Iraqis as the British had treated the Indians. Their failure to grasp the distinct contexts and timings of each occupation only exacerbated the situation. What compounded the Americans' lack of understanding was the emergence of alternative parties and figures from the Baathist era, who came to take control of the country.

The sectarian war between Sunnis and Shiites in the period 2006-2007 prepared the ground for an Iraq that overflows with various armed factions, extremist religious parties, and militias that do not recognize national identity as an inclusive identity. These groups strived for an Iraq under a trans-boundary Islamic caliphate, a nation which pledges unwavering obedience to the ruler – be he a caliph according to the Sunnis, or Al-Wali Al-Faqih, the supreme religious authority and deputy of the awaited Al-Mahdi, among the Shiites. Below these supreme leaders are countless figureheads and holy men who also demand obedience.

Even in retrospect, it proves difficult to unravel what had happened during the US occupation of Iraq as it actually happened. The tangled threads of geography, history, culture, religion, clans, and nationalism all interplayed in the events that transpired. However, perhaps statistics can give a general idea of the insurmountable tragedy that had befallen the country and its people.

In 2006, the British medical journal “The Lancet” issued a study entitled “Mortality before and after the 2003 Invasion of Iraq: Cluster Sample Survey.” The study revealed that the war amassed a death toll of around 655,000 Iraqis since 2003. At that time, this number represented 2.5 percent of the total population. The study stated that 56 percent of the victims were killed by US army bullets, 13 percent by car bombings, 13 percent by air strikes, and 14 percent by shelling.

Washington established a new system based on ‘muhasasa,’ a quota-based political system through which thieving factions, empowered by arms and corrupt money, were able to take over the state’s institutions. This system was consecrated through the disastrous methods of Paul Bremer.

The sectarian war between Sunnis and Shiites in the years 2006-2007 laid the foundation for an Iraq that teems with various armed factions, extremist religious parties, and militias that do not recognize national identity as an inclusive identity.

ORB Center (2) has calculated a different, more harrowing figure, in a study with an error margin of 1.7 percent. The study stated that the number of Iraqis killed as a result of the US occupation exceeded one million until August 2007. The numbers did not include the deaths in Anbar and Karbala governorates. In Baghdad alone, 40 percent of families lost at least one of their members. 40 percent of those were killed by US army bullets, 21 percent were killed in car bombings, 8 percent were killed in air strikes, and 4 percent were killed as a result of the sectarian war.

The death toll did not stop at 2007, when the study was concluded. It has tragically continued to rise at an unyielding pace, reaching a climax with ISIS invading large areas of the country, and marking the beginning of another harrowing chapter in the war saga, with many more dead and more than 7 million refugees and 8 million internally displaced persons in Iraq and Syria. As for the United States, the war cost it 5,000 soldier, in addition to a staggering $ 2.9 trillion, according to the reports of the ‘Cost of War Project’ at Brown University.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabah Jalloul

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 11/08/2023

The folder “Twenty Years since the War on Iraq” is a joint production between Assafir Al-Arabi and Jummar, with the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation.

1- Qur'an 5:32, Surah Al-Ma’idah.

2- A US-based digital newsroom and journalistic organization.