This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Prologue: How far we have fallen

The prospects for Palestinian national liberation have never been simply about the relative power of the two parties, Palestine and Israel, in a struggle that rages a century on. Both parties have always been allied with, or anchored in, external powers and states with a political or strategic interest in the still unresolved question of which peoples should have which rights in Palestine. While the Zionist settler colonial project from the outset received essential sponsorship, legitimacy and funding from colonial and imperialist powers, Palestine’s strategic depth has always been among the Arab peoples, rooted in the concept of the Arab nation and its primary cause, Palestine. Palestinian national liberation prospects have appeared more or less promising depending on the scope and depth of Arab popular and official support.

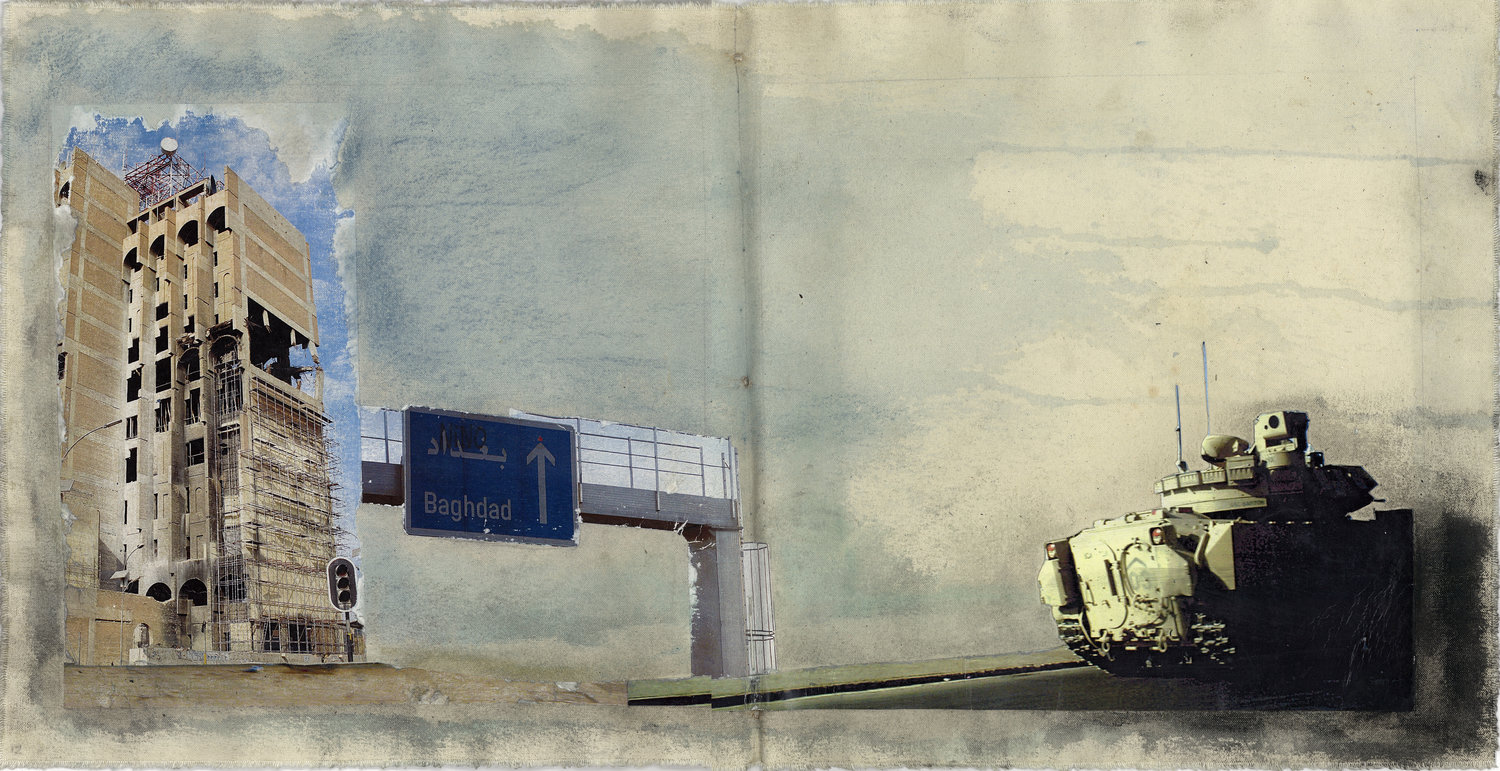

My story of how a once-unbreakable bond of Arab solidarity with Palestine has been shattered and diffused, with only a handful of Arab states today still faithful to that pan-Arab principle, begins in 1978, in Baghdad. A high-point moment in PLO relations with the Arab states was enshrined in the Arab Summit of “Steadfastness and Confrontation”, when the Arab states rallied around the PLO, the newly baptized sole and legitimate representative of the Palestinian people, in the wake of the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty. That shock had been the first break in the wall of the historic Arab position of “No Peace, No Negotiations, No Recognition”. The rhetorical Arab position towards Israel contrasts with the de-facto recognition of Israel through Arab acceptance of UN resolution 242, which signaled the end of the Arab-Israeli “struggle” as far back as 1967, and its transformation into a series of battles/conflicts, most of which have now been resolved.

That new Arab alliance, effectively headquartered in Baghdad, remained faithful to its commitment to support Palestine economically and diplomatically, and to continue to isolate Egypt from the Arab League for many years following. Yet this embrace proved fatal for the PLO in another way, as it ended up forcing Yasser Arafat into the camp of Arab states who refused to condemn Saddam Hussein for his invasion of Kuwait, viewing the US led campaign as serving to defend and Israel and establish an imperial footprint in the region after decades of post-colonial politics.

This not only meant the further break-up of the pan-Arab solidarity network for Palestine, with the powerful and rich Gulf states (and Egypt) firmly allied with the USA against Iraq. More significantly for the PLO, as the weakest chain in the pro-Iraq alliance, it suffered the most from the blowback of its risky, and ill-conceived, position in support of one Arab bloc against another. While the PLO had faced off in violent battle over the decades against a number of Arab states (Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Libya and Iraq itself), it had generally been above the fray, trying to adhere to its official position of “non-intervention in the internal affairs” of its Arab brethren.

Between the impacts of the first and second wars against Iraq, the much vaunted PLO slogan of “the independent Palestinian decision” was trampled under the boots of global imperialist and regional reactionary powers claiming the high ground of democracy, good governance, human rights and privatization. Yet today, despite the past decades of war, slaughter and destruction in Palestine and among too many of its brethren Arab states, and with Arab-Israeli normalization the latest fad, neither the flame of Palestinian national liberation struggle, nor that of democratic revolution among the Arab peoples have been clearly extinguished.

The Effects of the First Gulf War on the Palestinian National Liberation Movement

The fallout of the first Gulf war on Palestine was swift, cruel and collective, with long-lasting political consequences. These may be summarized under four key impacts.

1. Economic and social impacts

The bitterness of Palestinian defeat at a moment that liberation seemed reasonably attainable was only intensified by the terrible toll on Palestinian society and economy. The Arab funding of the PLO (official and popular) that had been essential to PLO survival in its post-1982 Arab exile ceased in August 1990 and within a few months the PLO was unable to pay its military and civilian and other staff around the world, with no illusions about this being the only price it was to pay for its support of Saddam Hussein.

Most significantly, in the wake of Kuwait’s liberation, Palestinians living in Kuwait, many for decades, and who played an essential role in managing the country’s public services and economy, were viewed as PLO supporters of Iraq, and treated accordingly, regardless of the individual concerned. Over 400000 Palestinians were obliged to leave Kuwait and the Gulf countries in the wake of the Iraqi withdrawal, leaving behind homes, jobs, lives and futures.

Is the apparent willingness and ability of thousands of young, desperate and brave Palestinians to renew and recreate modes of armed struggle and Arab popular resistance to despotic regimes and predatory capitalism not one and the same struggle? And does it not seem that neither Israel’s military supremacy nor any degree of Arab despotism can suppress resistance, however much the balance of power between the forces of revolution and reaction remain asymmetric?

Most returned to Jordan and Palestine, unable to relocate in other Gulf countries which began restricting Palestinian expatriate populations no less important to their economies. The social fragmentation that this new Palestinian exodus entailed had immediate economic repercussions, with families again cut off from each other, transformed from providers of hundred of millions of dollars in annual remittances to both Palestine and Jordan, to unemployed, penniless refugees.

The Resurgent “Arab Economy” of Palestine

30-05-2021

The shock to the PLO of the Arab financial boycott which lasted for five years, further softened it up for what was to come in the form of the Oslo Accords and their favoring of pragmatism over idealism, something which the PLO leadership had already largely bought into since 1974. But the impact to the local economies was no less lasting: only once the intifada had been extinguished and a new Israeli “peace” government elected in 1992 leading to Oslo, was it possible for the PLO to redefine its conditions for “Peace, Negotiations and Recognition” and try to drag the Palestinian national movement and people along into this historic compromise.

2. The first intifada, isolation of the PLO in the Arab world, and the Madrid Conference

Most Arab states which had opposed the US-Gulf coalition against Iraq could withstand the break in relations this entailed. But for the PLO, the Arab official boycott had disastrous impacts at a moment when the first uprising had begun to gain its own traction in terms of international attention and Arab popular solidarity. That boost had led to a US-PLO political dialogue with Arab shepherding, and the PLO declaration of the independent state of Palestine as a historical compromise, in 1988.

By 1991, PLO hopes for a Palestinian driven peace process building on the intifada and renewed Arab solidarity with Egypt back in the fold, had been dashed. Its Ambassadors were no longer welcome in the halls of Arab power, with Arafat himself increasingly isolated in his exile of Tunis, far away from the action. However the victors, Arab and international, not only had to display their appreciation of the core issue in the region, Palestine, but also could not ignore the still smoldering Palestinian uprising which by 1991 had been transformed into mainly armed guerrilla resistance.

Between the impacts of the first and second wars against Iraq, the much vaunted PLO slogan of “the independent Palestinian decision” was trampled under the boots of global imperialist and regional reactionary powers claiming the high ground of democracy, good governance, human rights and privatization.

Hence, the Madrid International Conference on Peace in the Middle East, convened in 1991 and from which two tracks of negotiations were launched: Jordanian/Palestinian-Israeli on the core conflict, and multilateral on regional issues, including Israel. While this international conference had long been a PLO demand, its participation was limited to back-room directions to a Palestinian delegation from inside Palestine. Presumably, both Israel’s and Arab states’ refusal to allow the PLO to take the Palestinian seat was a rude reminder that the PLO was no longer the only master of its destiny. So the Iraq war may have opened a door to peace for Palestine, but the Madrid terms dictated by the victorious allies against Iraq, were so skewed against Palestine, that we ended up with Oslo!

3. End of the myth of the possibility of Arab military superiority over Israel

So much of Arab nationalist history has been chequered by the extraordinary claims, rarely backed-up by the eventual historical record, of Arab potential to destroy or defeat Israel (imminently) on the battlefield: in 1948, in 1967, in 1973 and in 1982. There remain many ideologues even today of this option: if only there had been a will, if only we had developed our military industries, if only we had secured the best Soviet weaponry, if only we had democratic regimes with popular support… the ifs are many.

In contrast, there have always been “moderate” Palestinian and Arab politicians, who either did not believe in the strategic possibility of Arab military victory against the more technologically advanced Israeli forces, or others whose interests were allied with neo-colonial or Zionist ambitions to deny Arabs the means to confront Israel on a balanced footing. The emergence of PLO armed struggle in the 1960s helped to redress the balance, at least visually, but Arab armies remained on a defensive posture, even when producing some battlefield results against Israel during the 1973 war, while the PLO military experience in Lebanon had come to its heroic and fiery end in Lebanon in 1982.

The Arab funding of the PLO (official and popular) that had been essential to PLO survival in its post-1982 Arab exile ceased in August 1990 and within a few months the PLO was unable to pay its military and civilian and other staff around the world, with no illusions about this being the only price it was to pay for its support of Saddam Hussein.

The shock to the PLO of the Arab financial boycott which lasted for five years, further softened it up for what was to come in the form of the Oslo Accords and their favoring of pragmatism over idealism, something which the PLO leadership had already largely bought into since 1974. The impact to the local economies was no less lasting: the intifada had been extinguished and a new Israeli “peace” government was elected in 1992 leading to Oslo.

Even after the 1982 Lebanon defeat of the PLO, and the further defeat of the Gulf War, as Iraqi ballistic missiles rained down on Israel in 1991, Palestinians took to the rooftops to cheer their savior Saddam Hussein, who had finally shown Arab military prowess. When it turned out that most were fitted with normal explosive heads, some Palestinians attributed this to Saddam’s strategic prowess. This mass deception (illusion) of the 1990s as to whether Iraq had the N-weapon and would use it as a last resort, propagated by Israel above all, came crashing down by 2003 for any Palestinian hold-outs, along with the remnants of the pan-Arab nationalist empty promises of a brutal and dictatorial regime.

4. Oslo and its historical compromise

For the cause of Palestine, there was a greater injustice that the earthquake of the first Gulf war generated, along with the collapse of the Soviet bloc ally. From Madrid to Washington, ending in Oslo in 1993, the PLO committed to terms that compromised the feasibility of pursuing any feasible strategy of national liberation. Its hopes for an international commitment to an end of occupation and settlement, and Palestinian independence, were postponed to after an interim period of self-governance supposed to last 5 years, but which endure today. Historians will continue to debate whether the compromise that entailed the return of the PLO, and the center of struggle, to Palestine could have, should have been avoided. But no doubt, the first war created conditions that ultimately distorted the Palestinian national liberation movement and agenda.

Once the PLO had signed off on Oslo and subsequent accords, it not only gained its long sought after foothold in Palestine with a semblance of autonomy, but also an international legitimacy it had never enjoyed, and a return to the Arab fold. However, as the past thirty years have demonstrated, Arafat’s strategy of “escaping forward” came to its final painful conclusion with the second intifada, launched as a revolt against the broken promises of Oslo that he had believed, his besiegement and eventual assassination by Israel. The limited gains of Oslo remain the only ones Palestinians have been offered in return for maintaining international acceptance and abandoning armed resistance. Even those terms (of surrender?) appear preferable to those plans the Zionist racist right in power in Israel is considering for the Palestinian people today.

The Second War on Iraq and the Quest to Eliminate the Palestinian Question

The developments of the 1990s set in motion dynamics that played out in Iraq and Palestine, coming to a head in 2003. Indeed the first war continued with unprecedented sanctions imposed on Iraq throughout the 1990s, turning it into a pariah among brethren and enemies alike.

1. Exposing the deception of the promises of the peace process, the second intifada and the war on terror

By the end of the agreed Oslo interim period, the time had come for the PLO to exchange its velvet gloves for boxing gloves. The attempt by Arafat to hold up the Palestinian national red-lines (thawabit) at Camp David revealed the true Israeli position of No Peace, No Negotiations, No Recognition. It seems that the old warrior, still impervious to Iqbal Ahmad’s and many others wisdom regarding the feasibility of waging armed struggle against Israel from outside or within Palestine, resorted (as in 1990) to what he and most of the PLO perceived as the only remaining option. The initially mass non-violent second intifada soon transformed into armed Palestinian-Israeli warfare that lasted five years and brought the PLO, now bereft of its founding leader, to its knees.

Presumably, both Israel’s and Arab states’ refusal to allow the PLO to take the Palestinian seat was a rude reminder that the PLO was no longer the only master of its destiny. So the Iraq war may have opened a door to peace for Palestine, but the Madrid terms dictated by the victorious allies against Iraq, were so skewed against Palestine, that we ended up with Oslo!

Before Yasser Arafat had been defeated, and in tandem with the emergence of Hamas (and eventually other factions’) suicide bombings targeting civilian targets deep inside Israel, the elephant in the room of the coming second war on Iraq had shown itself, in the form of the September 2001 attacks on the heartland of the USA. The Palestinian resistance was immediately conflated by Israel and the US with Islamic Qaida terror and the Iraqi weapons of mass destruction threat. Not even the photo-op of Arafat donating blood to victims of 9/11 could dispel the image, with the reality meaning little in the build up to the war.

So the “war on terror” became (and continues as) a joint Israeli-US-NATO mission, targeting (Islamic or other) Palestinian armed resistance to Israeli occupation, legitimate under international law, as part of the same terror threat of Qaida and later, ISIS. It also paved the way for coopting the PLO in the post-Arafat era into a range of political, economic and security bargains with Israel that restrict its autonomy, and prevent it from even trying to achieve independence.

2. The last stop of the independent Palestinian decision

A natural corollary of the end of the Arafat regime and his way of doing business, was that the successor regime not only had its wings significantly clipped, but that its decisions became increasingly subject to the influences of external forces. Negotiating options and positions became entwined above all with Jordanian-Egyptian interests in their own relations with Israel, regional and global powers. The Mahmoud Abbas regime was repeatedly drawn into rounds of fruitless but energy consuming “peace negotiations”, until any pretense of a peace process was abandoned with the last Obama-Kerry attempt of 2014. The PLO accepted Quartet imposed political conditions that undermined the possibility for Palestinian democracy encompassing Hamas, while locking in “security coordination” with Israel and the USA that remains the major point of contention in Palestinian internal politics.

For the cause of Palestine, there was a greater injustice that the earthquake of the first Gulf war generated, along with the collapse of the Soviet bloc ally. From Madrid to Washington, ending in Oslo in 1993, the PLO committed to terms that compromised the feasibility of pursuing any feasible strategy of national liberation.

Meanwhile Palestinian economic policies, strategies and priorities became largely hostage to international financial institutions and donor agendas, under the same template “reforms” being initiated in the newly “liberated and democratic Iraq”. In both Palestine and Iraq, traditional governing power structures and political norms were replaced with a formula designed in DC and imposed wherever globalization, liberalization and privatization waves hit around the world. Gulf Arab states had already joined the Washington Consensus and abandoned visions of Arab regional economic integration, instead opting for ties with the advanced economies of the OECD. But both countries were ripe for laboratory experiments that were abandoned in swift succession, leading to the weakened, externally-dependent regimes in Baghdad, Erbil, Ramallah and now, Gaza.

3. Opening the way for Arab-Israeli normalization

It is not surprising that all Arabs suffer the results of two massive wars against Iraq, an ongoing war against the Palestinian people under occupation, a series of Arab civil wars in Syria, Yemen, Libya, and heavy doses of economic liberalism, structural adjustment and imported democracy agendas in Palestine, Iraq, Egypt (and soon to come, Syria, Lebanon and any holdouts of the 20th century).

Probably the most dramatic outcome of the post-Iraq wars shocks, was the ultimate Arab regimes’ surrender to Peace, Negotiations and Recognition, with the final Act in that process being cooked in 2023. The first step toward explicit Arab normalization was dressed up in the traditional language of Arab solidarity of the Saudi-backed “Arab Peace Initiative” in 2002, which conditioned Arab peace with Israel on a just Israeli-Palestinian solution. So just as the first war of Iraq created the conditions for Arabs to sit at the same table with Israelis, so did the second war over a decade later expedite legitimizing Israel and its eventual (dominant) integration into the economic-security system in the region.

However today, even the modest red-lines of the Arab Initiative no longer retain any deterrent influence, with US spearheaded normalization of Israel’s political, economic, security and strategic relations with several Arab states already in the bag, and others touted as imminent. Regardless of the many factors behind the transformation of the regional political map and the relation of the Palestine cause to the peoples of the region, we have clearly suffered a strategic defeat for the cause and the for PLO’s room for regional maneuver, which historically was its major survival mechanism. The years 1990 and 2003 remain key milestone in that process.

4. The rise of the influence of the Islamic resistance

A final impact of the wars on Iraq that continues to ripple through the Palestinian national movement in a transformed global and regional landscape, is found in how the crushing of the Baath regime in Iraq was the end of many Arab nationalist dreams, including in Palestine. Just as marxist and communist resistance to imperialism in the region rose and fell, so did the promises of Palestinian nationalist and above all pan-Arab resistance, fail to deliver. The wars in Iraq were vital nails not only in the coffin of those aspirations, but also the clarion call for political Islam to enter the battle in its own reactionary language, violent means and new forms of organization. For many pan-Arab nationalists, Hizbollah’s armed struggle against Israel, and that of the (Islamic) resistance in Palestine, is viewed as a viable and effective revolutionary model for continued Arab and Palestinian deterrence of Israel, regardless of its other dimensions.

So the “war on terror” became (and continues as) a joint Israeli-US-NATO mission, targeting (Islamic or other) Palestinian armed resistance to Israeli occupation, legitimate under international law, as part of the same terror threat of Qaida and later, ISIS.

Regardless of the many factors behind the transformation of the regional political map and the relation of the Palestine cause to the peoples of the region, we have clearly suffered a strategic defeat for the cause and the for PLO’s room for regional maneuver, which historically was its major survival mechanism. The years 1990 and 2003 remain key milestone in that process.

Hamas was born in the first intifada and strengthened by the PLO and Arab nationalist failures of the first Iraq war. Similarly, the opportunity for being freely and democratically elected by the Palestinian people manifested itself in 2006 in the wake of yet another defeat of pan-Arab and nationalist PLO resistance. Today, even that version of an alternative to past resistance ideologies sitting in comfortable power in Gaza, has become a no less part of the problem facing the prospects for Palestinian national liberation than the impotent regime in Ramallah.

Epilogue: Can Palestine be the cradle of a new Arabism?

In twenty years, the underlying premise of a possible two-state solution has been transformed: instead of “(returning occupied Palestinian) land (in exchange) for (granting Israel) peace” is now one of Israel taking as much land as it needs in exchange for not continuing to wage war against Palestinians. A sad state of affairs, and one that could have not ensued without first destroying Iraq, and a few other Arab countries in the process.

Many questions remain, each of us may have a different answer. Has the flame of resistance truly been stamped out, once and for all? Beyond the symbolic and moral value of the new wave of Palestinian fedayeen, from Jerusalem to Gaza to Jenin, can we discern a new model of Palestinian freedom fighter, not attached to discredited regimes, to inspire Arab militants fighting for their political, human and civil rights? Is the apparent willingness and ability of thousands of young, desperate and brave Palestinians to renew and recreate modes of armed struggle and Arab popular resistance to despotic regimes and predatory capitalism not one and the same struggle? And does it not seem that neither Israel’s military supremacy nor any degree of Arab despotism can suppress resistance, however much the balance of power between the forces of revolution and reaction remain asymmetric?

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

The folder “Twenty Years since the War on Iraq” is a joint production between Assafir Al-Arabi and Jummar, with the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation.