This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Football did not rise from the graves in Iraq nor was it invented by the undertakers as the Najaf Club Ultras claim when they chant with every match: “Najaf, our beloved, you’ve taught them what football is”. The chant particularly reverberated when Najaf competed with some of the most revered classic clubs of the Iraqi football association: Al-Zawraa, Al-Shorta, Al-Talaba, Al-Quwa al-Jawiyya. Commonly referred to as "Al-Touba," which simply means "the ball", football in Iraq was a game of vast influence.

Football crossed the seas to arrive in Iraq. At the shores of Basra, English sailors kicked the ball for the first time at the end of the nineteenth century, when ships docked and departed, carrying goods and mail from Europe, through the Gulf, then Iraq, before they headed to India and other parts of south-east Asia. The people of Basra learned the game from the sailors and played it in the city where its popularity boomed in the schools and alleyways among the youth. In 1931, Al-Minaa (The Port) Club was the first football club founded in Basra.

Basra: the Song of the Marooned Fisherman

30-09-2015

When the British army invaded Iraq in 1914, they carried footballs next to the rifles, and football was invading the country, too. The game reached Baghdad, Habbaniyah, and Kirkuk, where Iraqis imitated the game that the British soldiers used to play in their camps for recreation. Football historian, journalist, and Coach Ismail Muhammad Ismail said that football spread from the old alleys and squares of Baghdad where boys used to make the Touba from old scraps of cloth which they folded and scrunched into a ball-like form and kicked around in the streets. Ismail notes that this DIY football was a staple of all games played in the poor neighborhoods until the time of the siege, as children could certainly not afford to buy any footballs (neither the nylon, elastic, or leather ones), so they stole their mothers’ stockings instead and stuffed them with rags and scraps to make themselves a free “touba”.

Football spread in Iraq not only as a game, but as something of greater significance with the establishment of the new kingdom. Tasked with outlining and structuring the state and its institutions, the monarchy was interested in creating connections between its novel institutions and society, and football provided one of those links. To this end, the state founded several football teams affiliated to its ministries and administrative departments in Baghdad and other districts of the country; a tradition which has persisted to this day.

The teams that were affiliated with the new state institutions were: the teams of the Ministry of Endowments, the Ministry of Finance, The Ministry of Works, the High School, the Teachers’ College, the Vocational School, the Military School (Aviation), the Public Printing Press, and the Education Forum team, among other institutions. During that time, the British largely remained “masters of the game” in Iraq; they managed it, put rules in place, and organized local tournaments. However, Iraqi archive documents reveal an early moment of the transformation in which football was approached as an act of “protest and resistance” by Iraqis who tried to manage football institutions in “more independent” ways, autonomously and separate from the temperament of the British occupation and its patronizing attitudes. Football stadiums have since been luring politics into their booths.

The British Colonel and the little Prince

In the beginning of March 1923, the English Casuals Football Club asserted its dominance in Iraq with a three-to-none win over the team of the Baghdad Football Association. Hence, it was decided that the first football championship in Iraq would bear the name of the English club, and 1923-1924 marked the first season of the “Casuals’ Cup”. A piece was published by writer Samir al-Shukraji in Al-Mada Newspaper at the time, celebrating the first ever “Iraqi management” of a local football tournament – despite the tournament’s British name.

The name was but the tip of the iceberg of the intricate administrative conflicts unfolding behind the scenes of Iraqi football. The Baghdad Football Association dubbed the tournament the “Baghdad Football Association Championship,” resulting in the tournament having two distinct names. The cup was of paramount importance to the leaders of the state at the time, so much that the Prime Minister Jaafar Pasha Al-Askari personally presented the cup to the High School Team in the final match in which it beat the Ministry of Works Team.

The British largely remained “masters of the game” in Iraq. They managed it, put rules in place, and organized local tournaments. However, Iraqi archive documents reveal an early moment of the transformation when football was approached as an act of “protest and resistance” by Iraqis who tried to manage football institutions autonomously, independent of the British occupation’s patronizing attitudes. Football stadiums have since been luring politics into the booths.

After the first tournament proved successful and reaped wide satisfaction among football fans, the Iraqi State and the British began to seek dominance in the world of football. The British have, in fact, realized the deeper meanings of the game since medieval times, when crossing with a football over into another village was a sign of defeating the latter. Conflicts which took the form of games led to violent incidents and murders, to the point where football was banned and criminalized by royal decree during the reign of King Edward III of England. The French Church at the time also forbade the game, branding it “malicious and dangerous”.

Perhaps one way in which football is “dangerous” is the way it cultivates an extreme sense of belonging, therefore creating an environment rife with intolerance and hate (in old and new fan bases), and nurturing steadfast rivalries with an opponent that must be defeated in order for the fan base to express joy in victory: an expression accompanied by gloating, teasing, and communicating pleasure at the failure of the other team – the sentiment perhaps expresses a tendency for violence.

In the second season of the Casuals Cup or the Baghdad Football Association Championship, the Baghdad Football Association - which co-organizes the tournament with the British authorities - issued several decisions, including the following: British players were not eligible for participation, the Military Academy Team was admitted to the tournament, stadiums were distributed to different teams, and four English referees were appointed to referee the matches.

Before the commencement of the season, the football association was dissolved, and its president, Youssef Izz al-Din Beik al-Nasseri, announced his resignation citing his desire to “devote his time to his own business.” The administrative board of the British Casuals Club swiftly regained control, taking charge of organizing the following tournament. However, the most politically significant incident that unfolded that season was the alteration of the coronation ceremony. After Iraqi Prime Minister Jaafar Basha al-Askari handed the cup to the winning team, the British authorities decided to introduce a new protocol by which Colonel Jobs, an advisor to the Ministry of Defense, handed the cup to the victorious High School Team that secured a single-goal victory over the Ministry of Works Team in the final match, in the presence of Nuri al-Saeed, then serving as Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces (and who would later assume the role of Prime Minister in 14 different governments during the monarchy era).

In the early 1930s, then crown prince Ghazi was eager to solidify his image as the “most beloved figure among the Iraqi people”. His growing popularity was fueled by his Arab and nationalist tendencies, setting him apart from the British court, which had its own loyal following within the new Kingdom. Hence, the Prince Ghazi Cup was introduced, held in conjunction with the Casuals Cup, which the British had organized every season since the early 1920.

The Iraqi press documented the events of the Prince's Cup final between the Wireless Communication Team and the Aviation Team, ultimately won by Aviation. The cup was presented to the victor by “His Highness the Prince” himself, seated in the VIP box alongside Iraqi politician Ja’far Abu al-Timman, who was a prominent figure in the resistance against British occupation during the Iraqi Revolt of 1920, leading several groups of the liberation movement in Iraq throughout the monarchy era.

As football gained increasing popularity among the youth in working-class neighborhoods and throughout Iraq’s cities, its institutional development within the state remained slow, even though the government acknowledged the game as a potential powerful connector between the State and the people. By the time the monarchy came to an end, all the ministries’ teams had turned into clubs, such as the Police and the Air Force Clubs. The Iraq Football Association was founded in 1948, and it joined the International Federation of Football Association (FIFA) soon afterwards. The Iraqi national football team was formed in 1951 and played its first friendly match against Basra, before its first international match in Turkey against Izmir.

The dictator and his son

In the aftermath of the monarchy's violent demise and the birth of the Iraqi republic in 1958, and up until Saddam Hussein's rise to power, football’s significance was very little within the volatile political landscapes and shifting republican regimes. On the other hand, the game’s popularity boomed on the streets and in working-class neighborhoods, as it continued to receive the sponsorship and support of the state, with government-funded clubs participating in local tournaments as part of government programs.

The most politically significant incident that season was the alteration of the coronation ceremony. After Iraqi Prime Minister al-Askari handed the cup to the winning team, the British authorities decided to introduce a new protocol by which Colonel Jobs, an advisor to the Ministry of Defense, handed the cup to the victorious High School Team.

The Iraqi press documented the Prince's Cup final between the Wireless Communication and the Aviation Teams, ultimately won by Aviation. The cup was presented by “His Highness the Prince” himself, seated in the VIP box alongside Ja’far Abu al-Timman, who was a prominent figure in the resistance against British occupation during the 1920 Revolt.

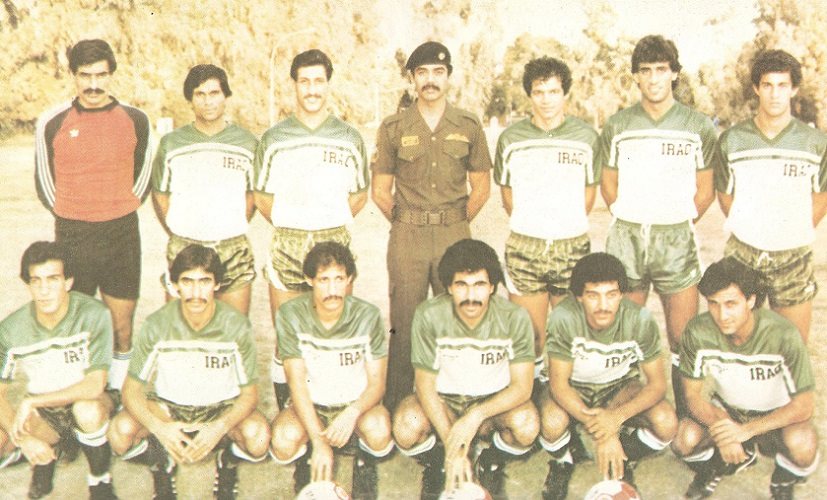

However, politics once again found its way into the box, this time through Saddam Hussein and his son Uday, who became known as “Ustad Uday” (Master Uday) after he assumed the role of Chairman of the Olympic Committee. But it was the president himself who had set the stage for taking over the game when he appointed his long-standing bodyguard Sabah Mirza as the head of the Iraqi Football Association. Uday, like father like son, had his own ideas about taking over the game. He proposed the idea of establishing a football club that brought together all the best players of the other clubs in one. What are all these different clubs for, anyway? All of Iraq’s champions were to swear allegiance to the leader, represented by the head of the Iraqi Football Association, and to his son. Uday’s Al-Rasheed Club summoned national team players from prominent popular clubs such as Al-Zawraa, Al-Shorta, Al-Quwa al-Jawiyya, and Al-Talaba.

When Iraq made it to the 1986 World Cup qualifiers in Mexico, the Iraqi regime saw it as an opportunity to showcase their "achievement." State television aired a special meeting between the national team and Uday Saddam Hussein, where the players dedicated their success to "the leader-president and Ustad Uday". The meeting was moderated by Mo'ayyad al-Badri, a veteran commentator and the host of the popular TV show Sports in a Week, and viewers had the chance to make phone calls and pose questions to both the national team players and Uday. One caller asked Khalil Allawi, the player who scored the crucial third goal against Syria's team, how he felt after his goal, to which he answered: "It is the feeling of any fighter who achieves victory for his country."

The Iraqi Football Association was founded in 1948 and it joined the FIFA soon afterwards. The Iraq national football team was formed in 1951 and played its first friendly match against Basra, before its first international match in Turkey against Izmir.

Following the war with Iran, the Iraqi army invaded Kuwait but eventually retreated after a battle that left it in shambles. The blockade was imposed on Iraq and the country was banned from hosting international matches on its soil. This marked the beginning of a new era characterized by the chant “This is how the besieged play... With determination, they have their way,” as football became a tool for the regime to whitewash its image in international and regional tournaments. This situation persisted until the US invasion of Iraq, during which the occupying forces and administration used Iraqi football to propagate the narrative that the US had liberated Iraq from Saddam Hussein, showcasing Iraq’s triumphs in championships and in competing globally in football.

Law No.111 in Iraq: Speaking Up is a Crime!

31-03-2023

Adnan Hamad, who served as the coach of the Olympic team during that time, shared an account of the then US President, George W. Bush, attempting to capitalize on the team's qualification for the 2004 Athens finals by trying to visit Iraq’s national team camp after their remarkable 4-0 victory over Portugal. At that time, Bush was seeking reelection for a second term, which he ultimately got. According to Hamad, Bush wasn’t the only one using Iraqi football to improve their image; the Iraqi National Democratic Party had asked him to write an article for their newspapers criticizing the occupation and Bush, which Hamad declined. While the Olympic team competed in the Golden Square in Athens, Iraq’s Al-Shaab stadium, which could accommodate 40,000 spectators, was turning into a US military base, after US aircrafts bombed its stands and pitch.

Football for a new Iraq

The shrapnel of the 2003 explosion of violence in Iraq had reached the world of football. The ultras were no longer intimidated by the authorities, and new political, sectarian, and even racist chants emerged during matches. Notably, during the derby matches between Al-Quwa al-Jawiyya and Al-Zawraa clubs, the former’s ultras provocatively chanted “Baathists! Baathists!” towards Al-Zawraa and its supporters, as the latter had been considered the Baath Party’s favourite football club. Such incidents escalated; in a Premier League match between Erbil and the Electrical Industries clubs in 2020, and despite bans on spectators at the matches due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the losing Erbil club's ultras stormed the Franso Hariri stadium and physically attacked the players and referees. A similar occurrence took place during a match between the Najaf and Karbala clubs, where guns were fired within the stands. These disturbances proved to be more than a few isolated incidents and have turned into an unfortunate recurring phenomenon.

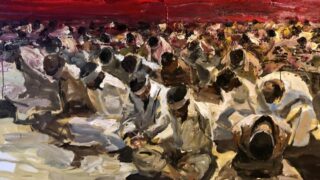

But there is another aspect to the football scene in Iraq. In the 25th Arabian Gulf Cup, everyone shared their unique experiences of witnessing Basra as it hosted the tournament after Iraq’s 43-year hiatus from hosting such events. Despite the challenging circumstances and the inevitable political exploitation of the occasion, Iraqi officials were in a frenzy, from the prime minister, the speaker of parliament, the ministers, all the way to the governor of Basra, and even Muqtada al-Sadr, who had previously forbidden football but now gave lessons on the importance of “obeying the coach”. However, amidst all of this, the crowd of football fans proved to be the most significant highlights of the entire tournament. Tragically, during the final match between Iraq and Oman, a fan lost his life in a stampede while entering the stadium, which was packed with over 60,000 spectators. Nevertheless, Iraq succeeded in snatching the Gulf Cup for the fourth time in its history, and the joy that sprawled the streets of Basra and all of Iraq on that evening was unparalleled.

Politics found its way back into the pitch, this time through Saddam Hussein and his son Uday, who became known as “Ustad Uday” after he assumed the role of Chairman of the Olympic Committee. The president himself had set the stage for taking over the game when he appointed his long-standing bodyguard Sabah Mirza as the head of the Iraqi Football Association.

The profound influence of football in Iraq became evident in 2007 when the Iraqi national team won the Asian Cup. Victory unfolded amidst the backdrop of a sectarian war in Baghdad and escalating violence in other regions, but Iraq’s national football team comprising players like Yunis Mahmoud (a Sunni), Hawar Mulla Muhammad (a Kurd), Nash’at Akram (a Shiite), and others, reflected an image of Iraq, a nation weary of wars and sieges. Hawar Mulla Muhammad's memorable gesture of raising the phrase “I am an Iraqi” remains etched in Iraqis’ collective memory. That championship was able to transform the atmosphere of violent sectarianism into a moment of overwhelming joy. Instead of dedicating the cup to the President and his son, the players dedicated their victory to the Iraqi martyrs who were killed by the US occupation. During that time, a popular song emerged, sung by several Iraqi artists, with the lyrics: “Do you see the footballer playing with his hand on his wound? This is our Iraqi player who brings us joy amidst tragedies.”

The title of the song is “We are the ones who made this stadium”, written by the poet Karim al-Iraqi. Women were also present in the stands.

In the year 2007, violence ravaged Iraqi society, with sectarian conflicts erupting in Baghdad and several other cities. Guerilla fights unfolded involving Al-Qaeda, the US army, Sunni resistance groups, and what are now known as the Shiite militias. Amidst the turmoil, walls of cities were covered with all kinds of ideological and political slogans and images, but Iraq’s national football team stole the spotlight. Pictures of the team’s stars were printed on shirts, plastered on walls and poles, and their uniform was popular among the small neighborhood teams. Iraqis discovered that united, they, too, could create joy in the face of adversity. Two Italian journalists, Max Civili and Diego Mariottini, captured these exceptional moments of joy in their book, A Goal against Bush. The book delves into the biography of Jorvan Vieira, the coach of the triumphant Iraqi team.

According to Vieira, winning the 2007 Asian Cup arrived at an exceptional time when the Iraqi people desperately needed a respite from wounds and sorrows.

Sectarianism may have been defeated on the field, but it continued to prevail in politics. Hussein Saeed, a legend of Iraqi football, resigned as the president of the Iraqi Football Association due to smear campaigns led by the Dawa Party. A similar fate befell Adnan Hamad, who was removed from his coaching position by the Minister of Youth and Sports, Jassim Muhammad Jaafar (a member of the State of Law Coalition led by Nouri al-Maliki). When Jaafar was asked in a TV interview about his removal of Adnan Hamad from the Association, he answered that Hamad had always been a Baathist who stood against the “new Iraq”.

The supplication of the players in the Iran-Iraq match became a collective prayer in Tahrir Square where thousands of young protestors gathered in 2019. The crowd’s elation at the winning goal resonated deeply, reflecting the emotions of Iraqi generations burdened by the violence of the Iranian regime.

In July 2006, a pivotal event unfolded in the "new Iraq" that shaped Iraqi sports, particularly football. Armed militias, disguised in Ministry of Interior commando attire, brazenly abducted Ahmad Al-Hajjiya, the first president of the Olympic Committee since Uday Saddam Hussein, in the bustling Karrada area of central Baghdad. Alongside him, 35 administrative staffers attending a conference at the Cultural Center of the Ministry of Oil also vanished. Their fate remains unknown, but their abduction marked a turning point for Iraqi football, as sectarian forces seized control of the game, changing it forever.

Now what?

Iraq’s victory goal over Iran, 2019

In 2019, Tahrir Square was teeming with the masses that had been taking part in the sit-ins for months to reform the political and social system in Iraq. Thousands of young people held their breath in overtime, as they watched the screen, waiting for the goal that would win them the match over the Iran at the Amman International Stadium.

In the 91st minute, Alaa Abbas delivered the match's defining moment with a decisive goal. The match was more than a game of football; it felt like a battle, and it was already unfolding in Tahrir Square. Amjad Atwan’s supplication as he skillfully executed the corner kick that found Abbas and led to the goal became a prayer amidst the fervor of Tahrir Square. The crowd’s joy resonated deeply in the generations burdened by the violence inflicted by the Iranian regime in present-day Iraq.

To Iraqis, football has been an outlet for their open joys and sorrows, but today, as the game becomes an international arena for business and power-plays, “Iraqi chivalry” is no longer enough to locally support the game. The individual hero, a single striker dubbed the “Lion of Mesopotamia” or the “team’s soldier” no longer suffices in the modern team-based styles of play.

This is where Iraqi football lags. The Iraqi Premier League suffers from poor infrastructure, lacking stadiums and training pitches. Funding remains inadequate, particularly when compared to the lucrative market of football clubs in the Gulf. Meanwhile, Iraqi clubs receive support from ministry budgets and affiliated institutions, relying on government allocations. To illustrate the situation, the highest market value of an Iraqi football club, Al-Shorta, amounts to $3 million USD, funded by the Ministry of the Interior, whereas the rest of the League’s clubs, comprising 20 teams, struggle with an annual budget ceiling of not more than $30 million USD.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabah Jalloul

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 17/05/2023