This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

According to the official spokesperson of the Ministry of Interior, flames consumed the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) of Southern Baghdad’s Ibn Khatib Hospital and took the lives of 82 people while 110 others suffered multiple injuries on Saturday evening, April 24th. The hospital receives patients of communicable and endemic diseases like measles, smallpox, typhoid, cholera, influenza, Hepatitis, Mediterranean fever, and undiagnosed fevers. The hospital was founded in 1962 and used to be a wing for armed forces designated for communicable diseases and later transferred to the Ministry of Health. Following the Covid-19 pandemic, Ibn Khatib hospital turned into a quarantine centre. Like its counterparts, the hospital suffers serious design issues, like lacking a system of CPR oxygen production and dissemination and rather relying, like the rest of Iraqi hospitals, on oxygen cannisters, lacking any fire suppression systems or emergency exists.

Iraq then announced three days of mourning, as officials rushed to offer their condolences and express their shock. The prime minister even wrote, like your average civil rights activist or social media blogger: “Where is that legion of maintenance workers? Where are the technicians? Where are the monitoring committees?” And many other “where-ares”.

A recurrent accident

This comes as no surprise, however. In August 2016, a fire that took the lives of 13 new-borns had spread in the premature maternity wing in Yarmouk Hospital in Baghdad’s Karkh. Minister of Health Adilah Hamoud then announced that she was “ready to resign were her ministry proven to have had a hand in that negligence”. A few days later, the spokesperson for the Ministry of Health noted that, according to the findings of the Committee of Expert Inspectors, this was arson. Still, 5 years and 4 different ministers later, who succeeded Hamoud, nobody was healthilty held accountable. This minister’s name would thus forevermore be linked with “shoes” following the supplies deal scandal valued at 900 million dollars and exposed in March 2017. It comprised the purchase of 26 thousand Portuguese “medical shoes” at 27 dollars a pair. She was also known as the “mobilisation minister” or “a child of authority” after pictures were circulated of her being celebrated by Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, former deputy chief of the Popular Mobilisation Committee and agent of the Shiite authority, Ali Sistani.

Sprained measures

Health authority measures in Iraq have long been mocked. “The virus only appears at night”, people would comment on the curfew imposed from 8pm till 5am. People also make fun of authorities imposing a (security) lockdown on some of the restaurants and cafes, glossing over luxury hotels flooded with clients who frequent it every night and create clouds of shisha smoke.

With the introduction of the measures imposed upon the second wave of the pandemic, “Jassim Gharib” would quickly become the star of the show. That faceless unknown citizen. The state, or what’s left of it, flexed its muscles and punished him with a fee of 25 thousand Iraqi dinars (17 dollars) for failure to wear a mask. This trending event coincided with Ministry of Health and Higher Committee for Health and National Safety guidelines stressing the importance of preventive measures last February.

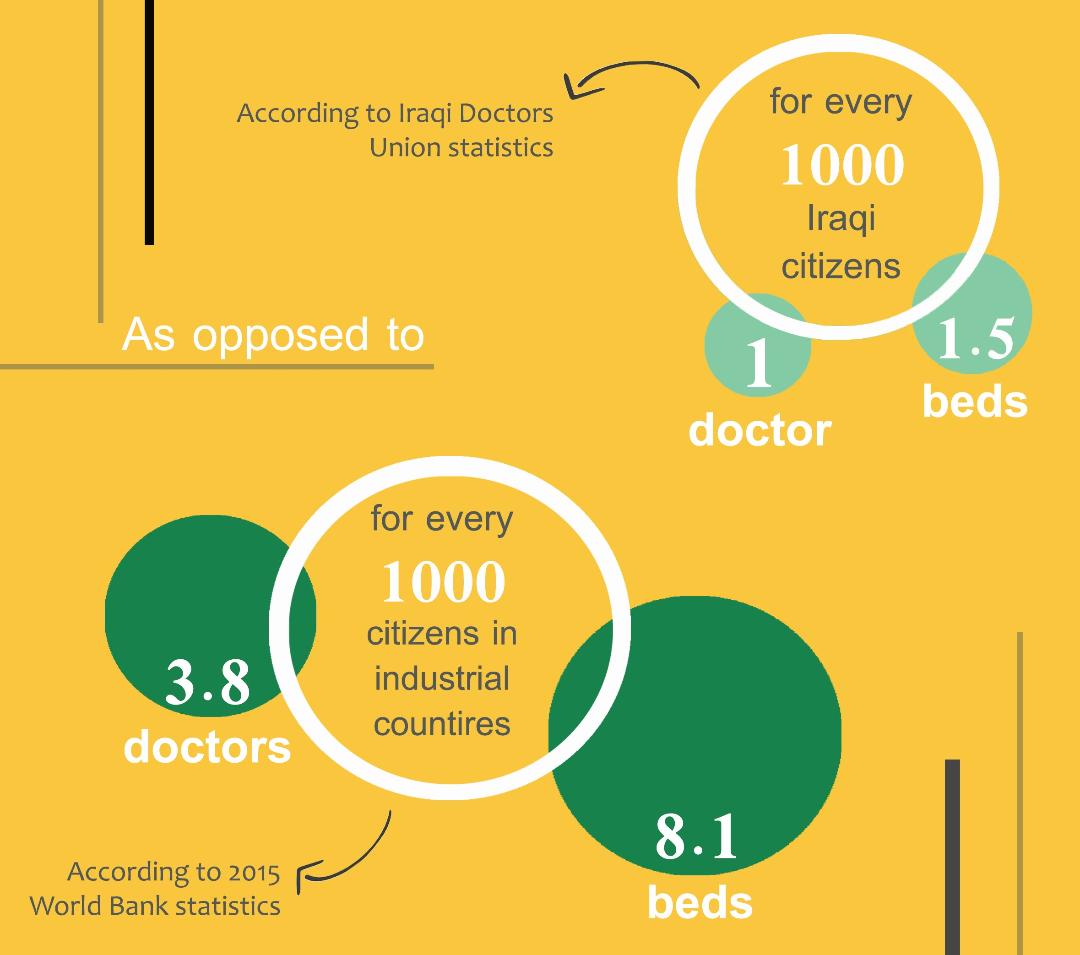

Iraqi Doctors Union leader said that “Iraqi hospitals had only 15 beds available per every 10 thousand individuals” (1.5 beds per 1000 people) while, according to the 2015 World Bank statistics, industrialised countries provided 8.1 beds per every 1000 of its citizens.

The “controls” (read random checkpoints) of the sanitary/security surveillance were to no avail – whose own agents failed to stick to the measures. Likewise, all quaking measures that the Iraqi health authorities enforced failed to face up to the risks of the Covid-19 waves: Iraq ended 2020 among the top Arab countries with the highest number of coronavirus cases and deaths, boasting of 597 thousand cases and 12.8 thousand deaths (the overall number of cases had reached 956,860, deaths reached 14,885, and, on the 21st of the same month, the number of coronavirus cases surpassed the million cases barrier, while the number of deaths went beyond 15 thousand by April 15th). A large pack of disasters has unfolded, exposing the health sector and showing, once more, how ruined it was. For instance, in June 2020, the city of Nasiriyah, known for its boiling popular protests in southern Iraq, was choking. Al-Hussein Hospital was out of oxygen cannisters as authorities rushed to point fingers of negligence at each other; for two weeks, however, they failed to rush to resolve the crisis, until they resorted to imported oxygen and donations from other countries.

Maps of Deprivation and Dissolution in Iraq

20-08-2015

For 14 months of life under the coronavirus, Iraq couldn’t halt the devastation. It equally failed to limit the severe repercussions instigated by lockdown and quarantine measures: the impoverishment rate in Iraq in 2020 reached 31.7 percent of the Iraqi population, now beyond 40 million people. According to the financial adviser of the prime minister, “there are more than two million Iraqi families that have joined households under the poverty line in 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic that has taken over the world”.

According to the spokesperson of the Ministry of Urban Planning, the rate has subsided – following lifting curfew measures to about 25 percent, but has been restored since, only to punish citizen “Jassim Gharib”. Nobody knows the extent of damage restored back with them. It is now known that the number of daily cases in Iraq has surpassed 8 thousand, mainly caused by, as the health authorities claim every now and then, “citizen uncommitment”.

Hope is thus suspended on vaccines to contain the coronavirus outbreak and its risks. In Iraq, the story of vaccine is no stranger to the rest of the stories of flounder and failure: the first of the vaccination rollouts in Iraq came in the form of a 50 thousand Sinopharm doses donated from China. Turnout to receive those was low, but people moved at a slightly faster pace towards vaccination when 336 thousand AstraZeneca doses arrived from Britain, followed by 50 thousand Pfizer doses, upping the number of vaccinated people in Iraq to 197,914 by April 15th, 2021. According to the UN in Iraq, the country is currently awaiting the delayed rollout of 1.1 million AstraZeneca doses through a COVAX grant. Previously, the Iraqi government had announced a Ministry of Health contract that states it would import 21 million doses that would “arrive accordingly”, failing to give concrete dates.

A corruption that devours hospitals and beds

Measures that the health sector experienced prior to the emergence of the virus, which made its first recorded appearance on February 24th, 2020, instantly creasing a crisis of shortage of hospital beds and buildings fit for quarantining cases. This is an age-old crisis and bound together with innumerable other crises.

In a recent statement, Iraqi Doctors Union leader said that “Iraqi hospitals had only 15 beds available per every 10 thousand individuals” (1.5 beds per 1000 people) while, according to the 2015 World Bank statistics, industrialised countries provided 8.1 beds per every 1000 of its citizens… who never stop protesting the low number of beds in light of the paced privatisation of health sectors, and which has started decades ago, uncovered by the coronavirus itself.

Public buildings were quickly prepared outside hospitals to contain beds to receive coronavirus patients. A total of 2,425 beds distributed over 4 locations in Baghdad. Some other places were similarly set up in governorates that suffered the biggest shortage of beds and health facilities. Notably, all those places quickly set up for emergency and later closed down were no proper sanitary environments and lacked, even following certification, supplies, equipment, and machines.

With the intensification of the first wave, the Ministry of Health announced its intention to “empty public hospitals to treat patients”; similarly, it proceeded to prepare some spaces – other than hospitals – dedicated for quarantining Covid-19 patients in need of intensive care: 525 beds in Baghdad’s International Exhibit Centre, 300 beds in the Peace Brigades building, a Sadrist militia building (Al-‘Ataa Hospital), 1000 in the internal wings of both Baghdad and Al-Mustansiriya universities, and 600 beds in hall of the Ministry of Youth.

The total number of beds is 2,425 distributed over 4 locations in Baghdad. Some other places were prepared similarly in governorates that suffered the biggest shortage of beds and health facilities. They were not all able, however, to fill the gap of beds deficit from which Iraq suffers. Notably, all those places quickly prepared and later closed down were no proper sanitary environments and lacked, even following certification, supplies, equipment, and machines.

According to the Healthcare Index issued by the Central Bureau of Statistics in 2019, most recent year covered by the health system statistics,

- The number of governmental hospitals in Iraq was 281 in 2018 and rose to 286 in 2019.

- The number of private hospitals in Iraq was 135 in 2018 and rose to 143 in 2019.

- The number of popular medicine clinics in Iraq was 339 in 2018 and rose to 344 in 2019.

All those institutions suffer absolute deficit in their systems, and the few available supplies and equipment suffer severe deterioration.

In 2009, the Ministry of Health contracted two companies to build 10 hospitals, each with a capacity of 400 beds. It later turned out that those two companies had no experience whatsoever in building hospitals, but were rather offered the contracts in return for hefty bribes that surpassed millions of dollars. Iraq pays its contractors in advance part of the determined budget. As such, while those hospitals were supposed to be delivered to the Ministry of Health in 2011, the two companies failed to fulfil their signed contracts and none of those hospitals have been delivered so far. Rumours have spread to the effect that the Ministry of Health has been delivered two or three of them; however, those are not yet operational as they lack medical cadres and also suffer other technical issues. It is unknown whether it is the result of low-quality construction and habitation.

Iraq: The Lack of a Political Economy Vision

29-03-2015

And it doesn’t stop there. Corruption, incremental following the siege imposed on Iraq in the early 1990s, has deepened after 2003 and created for itself new pathways and corridors in every sector. The health sector is no exception. For example, on September 5th, 2020, member of the parliamentarian health committee Jawad al-Moussawi announced that his committee has filed 30-40 corruption cases worth “billions of dinars” ever since the beginning of the 2018 parliamentarian term, all pertaining to the Ministry of Health, but which failed to be addressed by the Committee of Integrity.

A gap of scarcity: a maldistribution of everything

Besides shortcomings, underqualification, and corruption, Iraqi health institutions are bogged down in another issue: their geographic distribution.

In the province of Kurdistan, which has almost escaped the destruction of Iraq following the 2003 US invasion, civil war, terrorist organisation booby traps and their raids, it is noted that the level of healthcare is relatively higher than in the rest of Iraqi governorates. The region is home to 14-15 percent of the Iraqi population, but boasts of a quarter of cardiac rehabilitation centres of the country, and a third of its diabetes treatment centres.

In 2009, the Ministry of Health contracted two companies to build 10 hospitals, each with a capacity of 400 beds. It later turned out that those two companies had no experience whatsoever in building hospitals, but were rather offered the contracts in return for hefty bribes that surpassed millions of dollars. Those hospitals were supposed to be delivered to the Ministry of Health in 2011, but none has been delivered so far.

According to Central Bureau estimates, the Iraqi population has surpassed 40 million in 2020. The largest percentage of people is found in the capital, Baghdad – 21 percent, followed by the most ruined governorate, Nineveh at 10 percent, Basra at 8 percent, then Sulaymaniyah at 6 percent. Right below them is Dhi Qar, al-Anbar, Babylon, and Erbil, which all share a 5 percent per governorate of the Iraqi population, while Najaf, Salah el-Dine, Wasit, Diyala, and Kirkuk all share 4 percent of the population each, as each of Duhok, Maysan, al-Qadisiyyah, and Karbala are home to 3 percent each, and Muthanna Governorate has only 2 percent the Iraqi population.

Baghdad has 49 governmental hospitals, 50 private hospitals, and 62 popular clinics – infirmaries – that provide basic health services. It has the biggest numbers but remains poor in terms of quantity, quality, and random distribution. Baghdad’s rural areas, home to more than 13 percent of its residents, have no hospitals. As such, their residents are forced to cross long distances towards the busy centre, taking narrow and jammed routes, resigned to the fact that it is almost impossible for ambulances to reach these areas, and the Iraqi rural country in general, home to 30 percent of the Iraqi population across the different governorates.

The same applies to the rest of the Iraqi governorates, which vary in their institutions number and capacities, and are disproportionate to their population. Nineveh has 17 governmental hospitals, some of which are still in ruins, 3 private hospitals, and 21 popular clinics. In parallel, Sulaymaniyah has 38 governmental hospitals, 20 private hospitals, and 29 popular clinics. Dhi Qar, whose population outnumbers Babylon’s and comes close to Sulaymaniya’s, has 9 governmental hospitals only, 3 private hospitals, and 28 popular clinics. The Iraqi governorate with the smallest number of health institutions is Muthanna: 5 governmental, 1 private, and 9 popular clinics.

This demonstrates the random distribution of institutions over the Iraqi governorates, as well as the gap in their capacities, all of which are eventually deteriorated. Some could be categorised as out of service, considering their undeveloped equipment and infrastructure, lack of essential logistics, and chaotic operational management. This seems more evident in governmental institutions and is relatively less prevalent in private institutions. To each their price tag.

On September 5th, 2020, member of the parliamentarian health committee Jawad al-Moussawi announced that his committee has filed 30-40 corruption cases worth “billions of dinars” ever since the beginning of the 2018 parliamentarian term, all pertaining to the Ministry of Health, but which failed to be addressed by the Committee of Integrity. Besides shortcomings, underqualification, and corruption, Iraqi health institutions are bogged down in another issue: their imbalanced geographic distribution.

At the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak, private hospitals, and even some of the sector-wide hospitals (governmental-private) would turn away suspected coronavirus cases, and their doors remained closed until absolutely necessary, when they were announced open to quarantine patients.

All these institutions, be they governmental or private, have a problem in common – a key problem in Iraqi public health and hospitals, which manifests in shortage of cadres in light of the general demand, and applies to all medical specialisations “excepting dentists and pharmacists” – according to the Doctors Union.

Shortage in the number of doctors and medical cadres

A statement by the leader of the Doctors Union confirms the statistics that there is only one doctor per 1000 people of Iraq’s population, while the World Bank data points at 0.7 doctors for every 1000 Iraqis. According to the 2015 World Bank Statistics, 3.8 doctors are available to every 1000 citizens of countries with advanced health sectors.

The 2019 Central Bureau of Statistics estimates recorded a total of 35,005 doctors of all specialisations in Iraq. Recent medical graduates and recent members of governmental coalitions face a massive challenge that manifests in overwork, whereby some of them have 12-16 working hours a day. The government follows many methods to prevent them from migrating abroad, as they had been preceded by around 20 thousand doctors since the 1990s according to the Doctors Union. One of those methods includes refusing to issue their original certificates of graduation, limiting their circulation to state ministries and departments.

In terms of nursing, in 2018, Iraq had 2.1 nurses and authorised midwives for every one thousand people as opposed to 3.2 in Jordan and 3.7 in Lebanon according to the estimates of each country then.

An average doctor’s salary in Iraq is estimated at 600-900 dollars a month only (which doubles for those with higher education diplomas and seniority), while many look for side jobs in the private sector to increase their low income, especially after the Iraqi dinar lost dollar value this past December, while employee wages lost more than 20 percent of purchasing power.

Health is no priority of theirs

WHO data show that Iraq has spent a much smaller sum on individual healthcare than in more impoverished countries during the past ten years: an average of 161 dollars per person, as opposed to 304 dollars per person in Jordan.

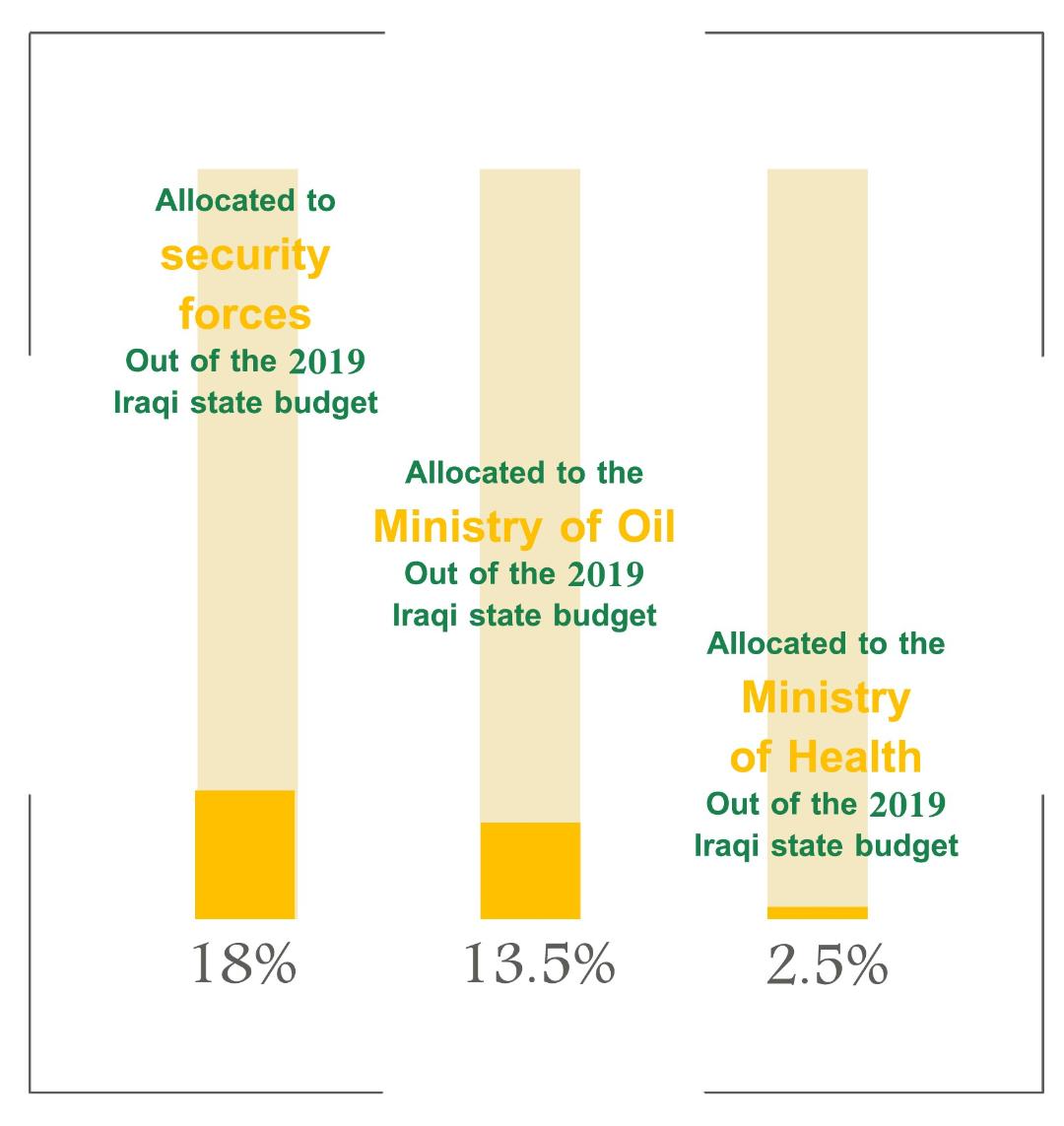

In 2019, for instance, a warless year, the government allocated the Ministry of Health only 2.5 percent of its state budget of 106.5 billion dollars. In turn, the security forces received 18 percent of the budget, while the Ministry of Oil received 13.5 percent.

Ministry of Health employee wages form more than 50 percent of the totality of allocation, while the percentage of medical allocation declined from 28.3 percent in 2015 to 24.7 in 2019.

The total number of doctors is Iraq, of all specialisations, is 35,005. Recent medical graduates and recent members of governmental coalitions face a massive challenge that manifests in overwork, whereby some work 12-16 hours a day. The government follows many methods to prevent them from immigrating abroad, as they had been preceded by around 20 thousand doctors since the 1990s according to the Doctors Union – one of which includes refusing to issue their certificates…

Since April 2003, the Iraqi Ministry of Health has been headed by 11 ministers from all scientific and professional disciplines and backgrounds. Among them, one thing is common: blaming a dearth of allocations, while some dared point fingers at the monster of corruption. Neither ministers nor dozens of directors who successively headed health sectors and departments have offered, however, anything to the level of public health in Iraq. Even the few who proposed reform projects were met with no ears to listen.

A lethal joke… medicine and a phase of plunder

Speaking of lack, medicine largely surpasses the rest of missing elements from the healthcare sector. In Iraq, people share a (sanitary) joke with paracetamol its protagonist – as these pills have replaced everything in hospitals and health centres. Nothing else exists, though it, too, faces a threat of extinction.

Iraqis are forced to buy their medicine, regardless of its kind and the disease it treats, from private pharmacies, with no price control, as there is no control over the import companies in the first place, which bring in the materials or supplies they distribute, and whose owners exchange services with influential politicians.

The public company for marketing medicine and medical supplies, the Ministry of Health (Kimadia), is in charge of coordinating and cutting deals for medicine, medical supplies, and equipment. In February 2020, Member of Parliament Bassim Khashan exposed corruption cases of “massive sums” in the company: “Kimadia is involved in the biggest case of corruption”. His speech, then, commented on the contracts of missing refrigerators – whose whereabouts are still unknown.

In 2019, a warless year, the government allocated the Ministry of Health only 2.5 percent of its state budget of 106.5 billion dollars. In turn, the security forces were given 18 percent of the budget, while the Ministry of Oil was allocated 13.5 percent.

Ever since 2008, exposed corruption files in the Iraqi Ministry of Health have reached a sum of 445 million dollars, pertaining to medicinal contracts, medical equipment, and an arson attack on strategic pharmaceutical warehouses in one of Baghdad’s neighbourhoods, which contained medicine worth up to 100 million dollars. All these sums haven’t been retrieved, and none of the governments has been able to fight the continuous plunder – as they failed to develop the sector of medical manufacturing or even sustain the one they had.

Iraq has two old medical manufacturers, Samarra’, which was founded in 1965 and began production in 1971, and Nineveh Medical Factory, located north of Mosul city, and which suffered massive destruction during Daesh’s takeover, then during its liberation from Daesh, and its rehabilitation was announced in early 2020. Otherwise, 17 factories are owned by private sector investors. Factories, whether governmental or private, have been working with a now relatively underdeveloped technology when compared with the progress of pharmaceutical industry. As such, they are excluded from the race to sustainably supply the Iraqi medical market, generating problems for importers – or smugglers.

Successive Iraqi governments that followed the 2003 US invasion of Iraq have struck such scripts with corruption, negligence, and plunder. Left alone to fight the threat of Covid-19 and extinguish the fires of corruption and mismanagement, Iraqi society is categorically convinced: their health or life has never been a priority to governments, parties, or coalition godfathers.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 29/04/2021