This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Amidst revolutionary stories and epic narratives, “small” details are often lost. Bouazizi, whose self-immolation sparked the “Arab Spring” in December 2010, did not die on the spot. Rather, he was first taken to the regional hospital in Sidi Bouzid. That medical institution had no department specialised in burns, however, and so Bouazizi was transferred to the University Hospital in Sfax Governorate. He was thus put in an ambulance once more, to cover a distance of 140 kilometres, in between life and death. He arrived at the University Hospital alive; there, however, it turned out that his state necessitated a transfer to the only hospital specialised in severe burns, located in the suburbs of the capital, Tunis. Bouazizi would now cover 270 kilometres to reach Ben Arous Hospital, where he finally took his last breath.

Ten years later, in December 2020, a young man named Badr Eddine Al-Alwi, who worked as a doctor in Jendouba (one of Tunisia’s poorest and most marginalised governorates), stepped into one of the elevators of the regional hospital he worked at to check in on his patients… but died on the way there: the elevator had no base, and no warning signs against entering had been posted. Later, public opinion would learn that this hospital has had a longstanding elevator problem, which officials in the Ministry of Health have been promising to resolve for years… to no use.

Son of a poor family that had bet on education as a social elevator, Al-Alwi died at the crux of a crisis in the Tunisian public health sector. There, the “white army” has found itself mobilised and drained in a warfront against a coronavirus pandemic. Even if it has imposed new challenges on the ground, this war has come to expose, or rather prove – what has already been known to the public – the deterioration of public healthcare and the variants of its chronic illnesses.

I- The coronavirus puts the public health sector to the test

On April 6th 2020, Nissaf Ben Alaya, new face of the National Centre for New and Novel Diseases, went on television, with pallor in her face and dread in her eyes, to state that failing to observe the lockdown measures will make the “dead outnumber the living”. The following day, former Minister of Health, Abdul Latif Al-Makki, stood before reporters, cried, and in turn complained about citizens’ “indifference”.

Were citizens truly to blame for frightening the ministry of health officials? These teary-eyed interventions came at a time the country had been living a full national lockdown and relatively “reassuring” pandemic numbers, especially in comparison with southern Europe or even some Arab countries: 623 infected, 23 dead, and less than 20 people in reanimation and ICUs. It seems, then, that the officials’ fears were rooted in other premises, perhaps most prominent of which is insight into the country’s healthcare sector.

When Tunisia recorded its first Covid-19 case on March 2nd, 2020, the overall number of ICU beds of all public, civil, and military healthcare institutions had not exceeded 300, of which no more than a third could be allocated to Covid-19 patients. Later, it appeared that most public institutions were unqualified to hospitalise virus carriers, and, as such, only some university hospitals would eventually be relied on, sadly located in but a few governorates. It meant bringing in patients that lived hundreds of kilometres away, bringing up the issue of transportation, medical first aid, severe shortage in cars supplied with enough specialists, medical equipment, and protective gear.

Later, Tunisians discovered that only one laboratory, affiliated with the Pasteur Institute, was equipped and specialised in analysing Covid-19 screening tests, and that the state lacked sufficient tools to conduct tests, store specimen, or even the chemical detector needed for analysis. Another issue that came up was the large shortage in anaesthesiologists and reanimation doctors, as well as medical oxygen cylinders and respirators (some of those that did exist wouldn’t even work or required maintenance).

That was the situation of the public health system in the early days of Covid-19 in Tunisia. How has it fared since - throughout and following the consecutive pandemic waves?

During the first coronavirus wave, Elias Fakhfakh’s government assumed a policy of extreme caution and a serious endeavour to decelerate infection rates and avoid disease clusters throughout the country, which would have been the demise of the healthcare system. The government therefore approved closing down educational institutions, mosques, cafes, and restaurants with the first sign of the pandemic. It suspended cultural, artistic, and sports events, closed borders, imposed a night curfew, then announced a full lockdown on March 22nd, 2020 that would last until may 4th, to be replaced by a lighter lockdown and a gradual lifting thereof.

On May 5th, the first wave resulted in 1032 confirmed cases and 45 deaths, relatively “good” numbers attained thanks to the efforts of the public health personnel and institutions, as well as popular commitment and solidarity, in addition to political choices that, regardless of all shortcomings and errors, matched the gravity of the situation.

The number of public health institutions in Tunisia exceeds 2300 units, while the public health sector employs around 50 thousand people: around 7000 physicians, more than 28 thousand healthcare personnel, around 2000 technicians and administrative staff, and more than 11000 workers.

The success of flattening a first wave with minimum harm possible - politics would soon reverse! After what looked like a “hudna”, disputes, conflicts, and manoeuvres resurfaced. Their initial aftermath was an overthrown/resigned Fakhfakh government in early July 2020, followed by another with a shifted pandemic strategy, prioritising economics at the expense of public health. Governmental change coincided with the peak of summer season; to a country primarily dependent on tourism and expatriate annual vacations, reopening borders would be nothing short of vital for the economy. However, only a small number of foreign tourists arrived, and no real preventative protocols were imposed on Tunisians arriving from abroad. As such, a second wave of infections broke out in August. Starting mid-September, confirmed cases would exceed 500 a day, naturally doubling the pandemic death toll.

Everybody expected strict measures from Hichem Mechichi’s government, but the country quickly adopted a policy of co-existing with the pandemic instead: point-blank refusal to announce a full lockdown, even if just for a short while, open borders even when new viral variants emerged, but also concurrently extending the capacities of the ministry of health and fortifying it to face the pandemic.

Perhaps the only positive aspect to this is its enhancement of the public health sector readiness to face the pandemic. It managed to increase the number of Covid-19 beds to more than 400 ICU beds, 2000 oxygen beds, (1) enlisting tens of regional and university hospital departments to receive and hospitalise patients from different governorates, and assigning field hospitals in inundated governorates such as Tunis, Monastir, Sfax, and Kairouan. The ministry of health taskforce would be backed up with tens of new ambulances, while the number of laboratories certified to analyse Covid-19 specimen increased to nearly 100 (three quarters of which are affiliated with the private sector).

Such politics come with a heavy human toll. By December, the country had crossed a threshold of 100,000 infections and 3000 deaths, where the second wave peaked at the beginning of February 2021, with a 200,000-threshold crossed and 7000 deaths. Things slightly quieted down in the following weeks but regained a sharp decline in late March, which indicates that the country has indeed entered its third wave: between 1500 and 2000 confirmed cases and around 50 deaths a day totalled 271,861 confirmed infections and 9293 deaths by April 10th, 2021.(2)

The vaccine is virtually the only hope out, but the vaccination campaign is going slowly - for a number of different reasons. One of the first is governmental slowdown and reluctance to bring in the vaccines – it relies to a large extent on the doses that the COVAX initiative promised to provide (around 4 million doses), and also those that allied states would grant. That is, in parallel with direct contracts concluded with manufacturers like Pfizer (2 million doses), Sputnik (half a million doses), and others. The second reason relates to logistics and human resources; vaccinating millions of people would require hiring large facilities to transport and store vaccines, but also to dedicate tens and even hundreds of special centres to receive vaccine recipients, and, certainly, to ensure enough physicians and paramedics in specific are available. By April 13th, 2021, the number of vaccinated people reached 154,647, of whom only 8,363 had received the second dose. (3)

II- Antiquated diseases

Apologists for the former Tunisian regime often repeated that the dictatorship had imposed profound reforms in societal structures and mentalities and formed an extraordinary public sector, especially in education and healthcare. They ignore, however, a number of facts, most important of which is that the gains achieved are insubstantial, that the first to strike it was the dictatorship regime itself, and that not all Tunisians enjoyed similar access to those gains, of which the public health sector might be the most prominent illustration of which.

An unequal and unjust health map

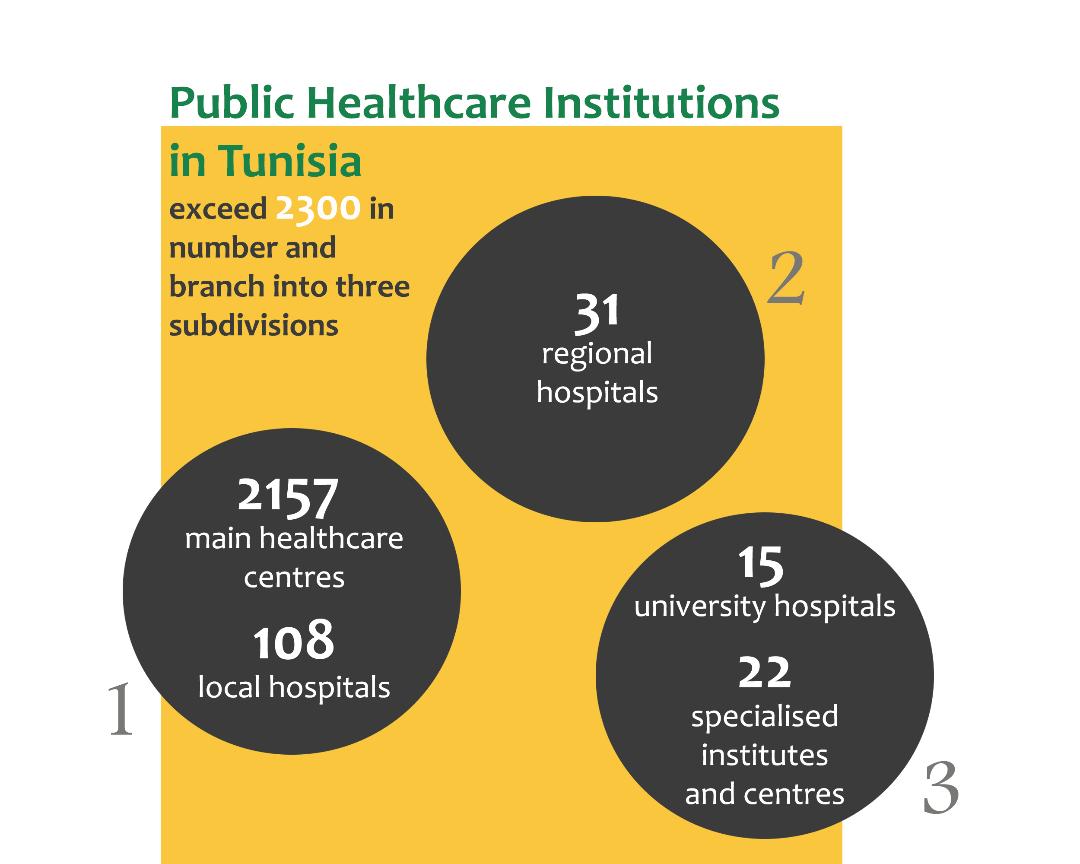

The number of public health institutions in Tunisia is 2300 units, which branch into three subdivisions: (4)

The first subdivision is made up of 1- Main healthcare centres (2,157 units in total), whose main task is to provide preventative and therapeutic healthcare services. And 2- Local hospitals (108 units in total), which, in addition to essential services, handle general medicinal services, childbirth, and urgent first aids – those contain hospital beds and equipment to diagnose some diseases.

The second subdivision is made up of regional hospitals (31 units in total), qualified to offer medical and surgical first aids, with hospital beds and diagnosis equipment available. Some of their departments could become more academized should they become competently staffed and adequately supplied with advanced equipment.

The third subdivision is made up of academic healthcare institutions, including15 interdisciplinary university hospitals and 22 specialised centres and institutes, which could be called the heavyweight arsenal of public health – as they boast the most significant human and material resources, and provide highly specialised treatments, all the while contributing to academic studies and scientific research.

To all these units may be added the college and university medical centres as well as family planning clinics and military hospitals. In total, these institutions provide 21 thousand medical beds.

As for scientific education, there are 4 medical colleges, one pharmaceutical college, and one dentistry college, and more than twenty schools and institutes for training healthcare personnel, such as nurses, medical assistants, technicians, and others.

As for human resources, the public healthcare sector employs around 50 thousand people: close to 7000 physicians, more than 28 thousand healthcare personnel, and around 2000 technicians, administrative staff, and 11000 workers. (5)

Those numbers seem plausible and decent… What’s the problem, then? Well, several intricate problems unfold, in fact.

First of those issues may be traced to the geographic distribution of healthcare institutions, integration between the first three subdivisions of public healthcare. The units of the first subdivision are distributed all across the country, but are incapable of diagnosing, treating, or characterising serious diseases, and offer no hospital beds. The situation is a little better in local hospitals, but the absence of specialised doctors and serious shortage of medical equipment, lack of reanimation and ICU beds reduces their efficacy.

In the second subdivision, that is, regional hospitals, other problems begin to surface: extreme shortage in the number of specialised doctors (especially in reanimation, anaesthesia, childbirth, paediatrics, and medical imaging), deteriorated sanitary equipment in surgery and reanimation wards, and shortage of ambulances.

As such, the third subdivision must make up for the shortcomings of more than 2200 healthcare institutions, resulting in overcrowded university hospital clinics, and minimal capacity in surgery and reception wards. It means deferred appointments by months, aggravated diseases, civilian anger, and an exhausted medical staff and paramedics. What’s more, university healthcare institutions exist in but 7 governorates out of 24 (Tunis, Sfax, Soussa, Monastir, Mahdia, Nabeul, Bizerte), all of which are concentrated by the coastline in the eastern part of the country. The result? Hundreds of thousands of Tunisians forced to pay extra money, cross hundreds of kilometres to undergo medical checks, surgery, or even just to buy medicine, many of whom use worn-out and crowded means of transportation.

The second of those issues pertains to human resources; while Tunisian doctors and paramedics are highly qualified and the number of graduates grew in recent years, most healthcare institutions are severely understaffed, estimated by healthcare unions at thousands of vacancies, around which the ministry of health attempts to turn either by ignoring it or exploiting new graduates through short-term contracts for lower wages.

University healthcare institutions exist in but 7 governorates out of 24 (Tunis, Sfax, Soussa, Monastir, Mahdia, Nabeul, Bizerte), all of which are concentrated by the coastline in the eastern part of the country. The result? Hundreds of thousands of Tunisians forced to pay extra money, cross hundreds of kilometres to undergo medical checks, surgery, or even just to buy medicine, many of whom use worn-out and crowded means of transportation.

The third issue is about the politico-economic choices the Tunisian state makes. From the mid-1980s until the mid-1990s, Tunisia entered a phase of “structural adjustments” and become an outstanding student of international financial institutions, led by the IMF. It joined the World Trade Organisation, adopted a number of programmes, and enacted legislation with the aim to “liberalise the economy”

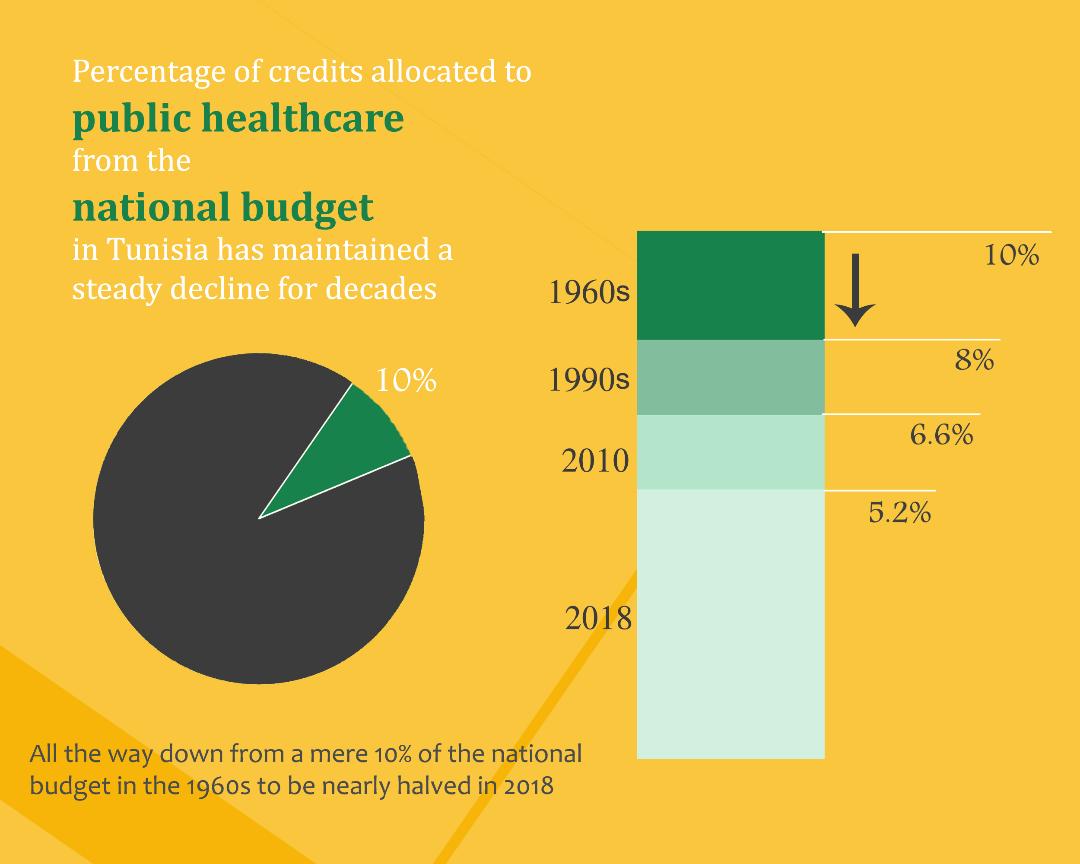

Naturally, such policies mainly targeted the public sector: budget cuts, frozen mandates, adopting a policy of temporary rather than permanent contracting, subcontracting private companies to carry out some of the public services, closing down some units, cutting back on equipment maintenance and renewal expenses, etc. One such example are the dwindling credits allocated to public health, which used to make nearly 10 percent of the national budget in the 1960s, but shrunk to reach less than 8 percent in the 1990s, all the way to 6.6 in 2010 and 5.2 in 2018.

A healthy man is a… rich man?

And as “chance” would have it, the decline in the public health sector ever since the late 1980s coincided with the private healthcare institutions experiencing a breakthrough in the 1990s and an ongoing and quick development ever since the early 21st century: 8000 doctors work in the private sector, over a hundred private clinics, 120 dialysis centres, more than 40 medical imaging centres, 13 birth and IVF centres, nearly 300 bioanalytical labs, 3 laboratories specialised in cytogenetics, more than 30 cell and tissue analysis labs, and 17 private medical transportation companies. (6)

Around fifty percent of new graduates migrate every year. Nearly 3000 doctors and 1500 nurses have migrated throughout the decade that followed the Tunisian revolution. Today, 160 anaesthesiologists and reanimation specialists work in the public sector, 250 in the private sector… and 500 abroad.

Credits allocated to public health dwindled. They used to make nearly 10 percent of the national budget in the 1960s, but shrunk to reach less than 8 percent in the 1990s, all the way to 6.6 in 2010 and 5.2 in 2018.

The appetite of the private sector hasn’t spoiled yet, however. It expects to lay its hands on vocational training – it has indeed already started constructing universities and institutes that, for high registration fees, provide courses in paramedical professions. Only medical and pharmaceutical diplomas are still exclusive to the state, although we don’t know for certain how long this “exclusivity” shall endure.

Losses come in many shapes and forms

Such problems and disasters the public health sector undergoes has been exhausting most of the population, who allocate a high percentage of their income to receive medical treatment and therapy through the private sector. Underpaid staff in the public sector, when compared with the private sector, or the privileges granted by Gulf or European countries, has equally cut in a new haemorrhage: around fifty percent of new graduates migrate away every year – nearly 3000 doctors and 1500 nurses have migrated throughout the decade that followed the Tunisian revolution. To gain a better understanding of the repercussions, one may quote one of the members of the Covid-19 Scientific Committee: we have 160 anaesthesiologists and reanimation specialists in the public sector, 250 in the private sector… and 500 who work abroad. (7)

III- Health shall not live by hospitals alone…

Public health is a political question par excellence; its boom and doom are tightly linked to public policies and socioeconomic choices in different areas. Even were a solid and fairly-allocated health infrastructure to have existed, there would still be other factors that largely affect the public healthcare system and its efficacy:

Quality of housing and access to public networks

At a time of pandemics and quarantines, matters like home space, architecture, and comfort, along with accessibility to public utilities, become vital to contain the pandemic and ensure people’s physical as well as mental wellbeing. 42 percent of homes in Tunisia are less than 100m2 in size, while primitive residences (huts and tin houses), although greatly decreased in number, are still close to 20,000 units. (8) Moreover, according to the numbers available through the Agency of Urban Rehabilitation and Renovation, (9) 1440 residential neighbourhoods, spread throughout the governorates, require rehabilitation.

Notably, 42 percent of homes have no access to sanitation networks, which is a median percentage, as it rapidly surpasses 90 percent in rural areas. (10) And while the ministry of health and the media call attention to the importance of washing hands, cleaning, and disinfecting, we find that more than 290 thousand houses lack access to a public water distribution system (11), not to mention the ongoing and long-lasting water cuts in many regions, especially in the inland.

Social Security

According to the statistics gathered in May 2019 by the Centre for Social Research and Studies (affiliated with the Ministry of Social Affairs) (12), 58 percent of Tunisians are covered by the National Health Insurance Fund (CNAM). A CNAM-insured person enjoys coverage limited to 300 dinars per year (around 120 USD, which is an extremely low limit when compared with the cost of examinations and medicine), with an increase by 75 dinars per additional insured dependent (who could choose between treatment in the public or private sector), exemption from the expenses incurred from some chronic and serious diseases, and coverage for the cost of some surgical operations, childbirth, expensive medical imaging, and the treatment of some rare diseases and incurable cases abroad.

As for the rest of Tunisians, however, that is, the poor class – only 7.3 percent have a free healthcare card in the public healthcare institutions (the white carnet), 17.5 percent have a discounted healthcare card (the yellow carnet), while more than 17.2 percent remain completely uncovered. That is, almost two million people with no healthcare coverage whatsoever. Such a number would appear “logical” when we consider the official statistics: the estimated figures of the informal sector are around one million and half a million people.

The state of the educational institutions

More than 1400 educational institutions have no access to public water systems, and supplies itself with water from unchecked sources. Nearly 400 institutions suffer from ongoing water cuts. At the infrastructure level, however, there are hundreds of educational institutions in which no toilets are available or which fail to meet the minimum conditions of to ensure their learners proper hygiene and sanitary safety. Austerity policies have also resulted in embarrassing and ongoing cuts to the budget allocated to the renovation, maintenance, and expansion of schools and institutes. Accidentally fallen and crumbling walls have become a frequent scene and shattered doors and windows a normal sight. Add to all that, the all-too-familiar overcrowded classrooms, especially in larger cities, where the average number of learners per class is 35.

***

The drained public healthcare system has been fighting Covid-19 at maximum capacity. It still stands, despite the limitations at hand and narrow-minded officials on top. The pandemic will lift, but facing reality is inevitable: public healthcare is sick and exposed, and is inaccessible to many Tunisians. But while sick, it’s not a hopeless case. And perchance the pandemic is a “blessing in disguise”. The people might realise that advocating for public healthcare is vitally necessary to ensure a minimum level of health security to both poor and middle classes.

With this article, Assafir Al-Arabi launches its folder on public health in the Arab region in times of Covid-19. This “folder” is published with support from the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 15/04/2021

1)See the plan the ministry of health devised to combat the novel coronavirus: https://cutt.ly/rvdLPsj [in Arabic].

2)The pandemic situation in Tunisia could be followed through the official page of the ministry of health: http://www.santetunisie.rns.tn/en/

3)The progress of vaccinations may be tracked through the previously noted link.https://cutt.ly/fvdZS7T [in French and Arabic].

4)Numbers provided from the National Institute of Statistics: https://cutt.ly/Nvf4rLK [in Arabic and French].

5)Numbers retrieved from the website of the Ministry of Health: http://www.santetunisie.rns.tn/fr/ [in French]

6)See the article “The healthcare system in Tunisia to face shortage in reanimation doctors, technicians, and nurses should the coronavirus infection rate continue to accelerate”. Published on the Radio Tunisienne website on October 15th, 2020: https://cutt.ly/WvfLu0M [in Arabic].

7)Numbers retrieved from the National Institute of Statistics: https://cutt.ly/Nvf4rLKSee the article published on La Presse newspaper website on December 25th, 2019. https://cutt.ly/YvfLDSv [in French].

8)Numbers retrieved from the National Institute of Statistics: https://cutt.ly/Nvf4rLK [in French].

9)See the article published on Anikfada website on March 6th, 2019: https://cutt.ly/hvfZe7L [in French].

10)Study conducted by the Centre for Social Research and Studies: http://www.cres.tn/uploads/tx_wdbiblio/resume-socle-final.pdf [in French].

11)See the article “Shadow Economy in Tunisia in Numbers, published on Kapitalis website on March 1st, 2019: https://cutt.ly/gvfZAF9 [in Arabic].

12)See the article, “Learners placed in the crossfire of coronavirus infections and a homeland incapable of providing water and a piece of soap,” published on Akher Khabar Online on October 10th, 2020. https://cutt.ly/ovfZ6Ie [in Arabic].