This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Part II: Graffiti, slogans and songs

The moment of October 17th effectively pushed the door open for all the Lebanese who took part in the mass popular demonstrations, into a space where they could celebrate a latent vitality and disturb a prolonged inertia which was in dire need of a jolt. The demonstrations, sit-ins and marches were serious, but they also often turned into popular festivities filled with music, dancing, singing, banners, banter and food, to the point that these “fun” activities caused a heated controversy between the different active protesting groups who debated the feasibility of these ways of expression, and wondered whether they were harmful or beneficial to the popular movement.

Many sneeringly asked the question, “Is this a carnival or a revolution?”, assuming that the movement was made superficial by all the “partying” which steered it away from its original urgent goals. At the same time, others described a “long-awaited popular joy”, which creates an atmosphere of togetherness, necessary for guaranteeing the longevity of the protests in the streets. But most importantly, these celebratory events mainly reflect the people’s desire to express themselves in all forms and ways, whether in text, music, chant or graffiti, and to share this expression with others in the squares and streets, in any way they could.

As with every popular movement, what happens in the fields of protest can be at once spontaneous, random, emotional, useful, confusing, or even harmful to movement, disorienting, and reductionist at times. It can also be a celebration of the long-awaited attempt at change that pushes towards new horizons in politics and effective action. Amidst all these possible approaches to the field, it remains absolutely essential to document what has happened and how people chose to express and present their ideas. It is important because it seeks an answer to the question: “What do people do when they are unable to do anything? How do they express themselves under such an impossible circumstance?”

Sound and echo: chants of the uprising

Perhaps the most widespread slogan of the October 17 uprising was the phrase “Everyone means everyone”. The slogan essentially meant that the people felt that “all” the political parties, figures, or religious sects they belonged to no longer represented them in any way, or in any position within the system. Many protestors were confessing to this feeling for the first time in their lives, admitting the shortcomings and corruption of those they once trusted and considered as their representatives in power, now labelled as part of the corrupt “everyone” whose removal they demand.

For the people, a lack of representation meant that their voices went unheard, and thus, they became confronted by the challenge of claiming and raising that voice themselves, through a popular movement.

Realistically and pragmatically, this “voice” cannot be a single and coherent one; rather, it is as multiple and diverse as the people and groups who partook in the movement in the squares of the various regions across the country.

Skimming through the many slogans and chants that were raised in the protests, one can single out some which were truly “trans-regional”. The phrase “everyone means everyone” was certainly the most prevalent of those. Also popular among the protestors was the so-called “Hela-Ho”, a chant inspired by the cheers of football stadium fans, transformed by the protestors into an obscene insult to politicians, particularly to the Lebanese Minister of Foreign Affairs at the time, Gebran Bassil, who – in fact – received the lion’s share of all insults.

In Beirut, feminist groups and activists were significantly prolific. They were visibly active and did not hesitate to proclaim their slogans and demands, ignoring the skeptics who downplayed the feminist cause by saying that the popular movement “was neither the right time or place” for their activism. They chanted greetings from “Beirut to Iraq, Yemen, Syria, Egypt” and other countries, supporting “revolutions in every country.” They also addressed the right of divorcée mothers to custody of their children, chanted against sexual harassment, and advocated the rights of all groups, especially women and LGBTQ+ communities. While these diverse groups were more frequently present in Beirut, other regions outside the capital city also found ways to express themselves in creative ways, and set up tents that held discussions on a wide range of topics, such as the economy and politics, while also tending to the logistics, such as distributing water and shielding the protestors from the sun and rain.

In the streets of Tripoli, the capital of North Lebanon, the catchy chant that echoed in every corner was “M’aalmeh, M’aalmeh” (“Hey, big boss, I know you’re corrupt… Hey, big boss, you’re sucking my blood”). In fact, the city saw popular sit-ins that almost outdid those in Beirut in their vastness, significance, and continuity. The famous “M’aalmeh” chant was written by the activist Tamim Abdo, in a clear Tripolitan accent which utilizes witty satirical phrases to criticize politicians. With its catchy tune, the cheer spread with great momentum, reaching Beirut and other regions where protests were happening.

Lebanon: A Special Type of Rent

13-12-2020

In Tripoli (and in other Lebanese regions as well), the title “m’aalmeh”, meaning something like “master” or “boss”, is usually used to address someone of higher status than that of the speaker, or to mock someone who believes he’s of higher status. In the context of the protest cheer, “m’aalmeh” refers to the Lebanese politician, particularly to Tripoli’s politicians who present themselves as responsible officials who care for their people and make extraordinary promises before every election season.

In fact, Tripoli’s ancient political families are many, and enormous amounts of money circulate exclusively in their hands, while the city and its inhabitants suffer from the highest poverty rates in the country. In recent decades, Tripoli has seen the growth of a wide gap between the ludicrous wealth of the its political figures and the steep poverty of most of its inhabitants, and the Tripolitans are increasingly aware of this. Tamim’s chants are often unequivocal in mentioning the corrupt political figures of the city by name. For example, one of his phrases says, “We will kick you out, Mikati,” referring to the former prime minister of Lebanon, Najib Mikati.

Many sneeringly asked the question, “Is this a carnival or a revolution?" Those considered that the movement was made superficial by all the “partying” which steered the protests away from their original urgent goals. At the same time, others described a “long-awaited popular joy”, which creates an atmosphere of togetherness, necessary for guaranteeing the longevity of the protests in the streets.

In those chants, both melodies and words work like a charm in winning people’s hearts. They are instantly memorized by everyone, as if they were old folk songs:

“Dearest (politician), may God protect you.

You don’t want to leave your seat, huh?

But we will make you.

We’ll grab our freedom ourselves,

And pull it out of your throat.”

The chants also address Tripoli’s “bad name” of recent years as a city defined by the clashes between the regions of Bab al-Tabbaneh and Jabal Mohsen (1), and as an alleged “incubator for extremist Islamist groups”. The chants mock these attempts to obliterate the city’s identity and spirit, and condemn the politicians’ repetitive exploitation of the Tripolitan youth for the sake of their own battles and benefits:

“They call me when there’s a fight,

and they say they are on my side”…

“Tebbaneh is the mother of all the poor,

and you pigs will fall!

Oh, beloved people of Mohsen,

We won’t let you down either!”

The lyrics mention the regions which are supposedly at odds, unifying the concerns of all the poor in the city from both regions which witnessed violent clashes that had exhausted Tripoli for several years... Thus, the chant becomes a stance that wittily accuses, exposes, and embarrasses those responsible for the suffering of Tripoli’s people. Usually, it always ends with another enthusiastic refrain which uplifts the locals’ spirits: “You great, you great, you great Tripolitan!”

“Hela-Ho” and music

Music has always been the close companion of popular protest movements everywhere. In all of the “Arab Spring” countries in 2011, and later in those countries that saw the 2019 uprisings, from Iraq to Lebanon, Sudan and Algeria, as well as in the “Black Lives Matter” protests in the United States of America and in other popular movements, music is always a common denominator.

In Arab music history, one finds tremendous examples of the use of song in popular mobilization, political criticism and satire, from Sheikh Imam and Ahmed Fouad Negm to Ziad Al-Rahbani, and their predecessors and successors who wrote sardonically witty lyrics and music… In the 2019 October Uprising in Lebanon, the classical “repertoire” of political songs was unsurprisingly updated by new musical releases more fitting for the new generations’ chosen ways of expression, and more relevant to their current affairs and problems. In fact, the new music wasn’t afraid to rescind the old, directing criticism at its shortcomings, and even accusing the artists and performers of those well-known “revolutionary” songs of being silent, even complicit in the current corrupt system. The consecrated contents and forms, too, were critiqued, and to many music content makers today, it was no longer acceptable to reproduce old templates or to ruminate the same phrases over and over again.

“El Rass” (Mazen el Sayed) is one of the rappers and music producers who released several new tracks after October 17, the first of which was “Shuf”, a song that was frequently played on loudspeakers in the squares of protest. The track has a fast-paced, enthusiastic beat that kept up with the rhythm of the street in the first few weeks of the uprising. The lyrics compile a group of responses to all the things the uprising was accused of at that time. Some had said that the movement was an attempt to destabilize the country by a bunch of bandits, that it was an “obscene” revolution, or that it was run behind the scenes by corrupt political parties too… The song’s response to these accusations was: “Walid, Samir and Sami / take me for a fool / But my people is wide awake / my people is wide awake.” It refers to the sectarian political leaders (Samir Geagea, Sami Gemayel, Walid Jumblatt) who tried to ride the wave of the revolution and claim it as their own, but were quickly dismissed by the protestors who rejected these attempts. The track adds, “I block the street because the street is mine / I occupy institutions because institutions are mine/ It is a revolution for our rightful demands, not a clash between parties / a revolution for life, these are my slogans /… / My options are unlimited / these are my manners and morals / My people have shattered all idols / Let our impossible fall!” In this part, the song also defines the identity of the protestors and their goals.

El Rass says, “The refugee didn’t steal my rights / The Central Bank did / We are not Gebran Bassil (who wants peace with Israel) / Rather, we are death to Israel (Resistance) / We are not Bin Salman (the Saudi Crown Prince) / But you will resign nevertheless.” In this example, the song continues to refute the accusations raised against the revolutionaries, especially those that claim they are “agents” or subordinates. The lyrics attack racism, and reprimand some television channels that claimed that the demonstrators were supported by this or that country, or that they were not Lebanese, but rather “extremist” Syrians. In this context, one is reminded by some news reports which intentionally singled out Syrian young men in the demonstrations and asked them, with blunt racist implications, what they were doing in the squares, suggesting that they were “suspicious” individuals.

After “Shuf”, El Rass released the song “Nar” (“Fire”), in which he references the popular “Hela-ho” chant, appropriating it in his own way by making it into a kind of battlefield hymn that encourages the protestors/fighters to proceed: “Hela Hela Hela Ho… Take the fire in your guts and march forth!” The song exhibits great pride in the feelings of brotherhood and comradeship that prevailed among the squares, embodied by all those who do not know each other’s names, but who have nevertheless become a unified body; a family of protestors:

“I give all my trust to the man and woman whose shoulders support mine.”

“Let the whole world tumble! I don’t care, as long as my brothers and sisters are here, by my side!”

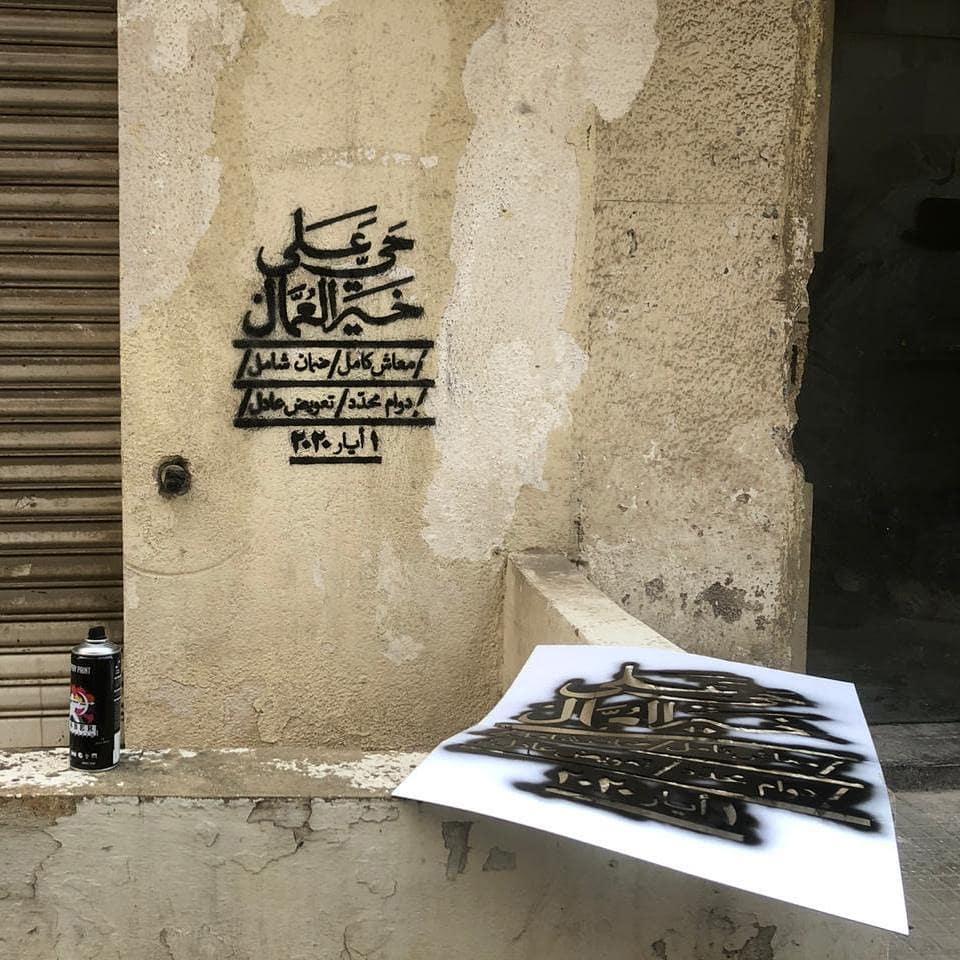

El Rass’ latest production in the context of the October uprising was a tribute to a “Ali Shuaib,” the man who became an icon after leading an attack on “Bank of America” in Beirut in 1973, and whose name was spray-painted on numerous bank facades by some of the October protestors, as a sign of their rage and a promise of retaliation.

Another rapper, Bou Nasser Touffar (2), also re-employed the “Hela-ho” in his track, titled “Tar” (“Vengeance”), in the verse: “Hela-Hey, I heed the call, Hela-Ho, one freedom is greater than ten shackles.” The track, which was released in August 2020, after the economic collapse already took effect and after the protests were halted, exudes a lot of pessimism and personal frustration, yet insists on individual resistance to all circumstances: “This country is my graveyard; took my life from me / If my family didn’t live here, I’d never call it my homeland / You still have hope? Well, lucky you / “Harakeh” will soon kill it off.” For instance, the rapper here chose to refer to a particular political party by its name (Haraket Amal), instead of keeping the verse ambiguous.

For almost ten years, Bu Nasser Touffar has had a legacy of rap songs made popular in the protest squares, the most famous of which is “Wasakh el-Tijari” (“Dirty Downtown”), a collaboration between Jaafar Al-Touffar and Nasser Eddin Al-Touffar, which bashes the commercial center of Beirut, “Solidere”, as a hotbed for plundering and corruption.

Rapper Jaafar Al-Touffar also produced songs of protest during the October uprising. He has always expressed his conviction that “insults and curses were the weapons of the defeated against the system that oppressed them” and thus become “acts of resistance”, especially important in the language of rap, which stems from the street and its people.

Jaafar Al-Touffar was in the protest squares since day one, live-rapping his old and new songs with other demonstrators. And just as Tripoli’s chants spoke in a local accent, so was Jaafar’s rap an authentic voice of Hermel’s highlands and its people. His song “Mamnou’” (“Forbidden”) begins with the words “Oh, downtown lights, the highlands are dark… Oh, mute justice, you never say what’s right.” The lyrics then address all sorts of issues, from the Israeli threat to the warlords-turned-politicians, to the daily economic concerns of a regular citizen: “Here’s to the man who has to raise two kids, so he sits and calculates his debt. Is this not a sin? How does this make sense?”, the song asks...

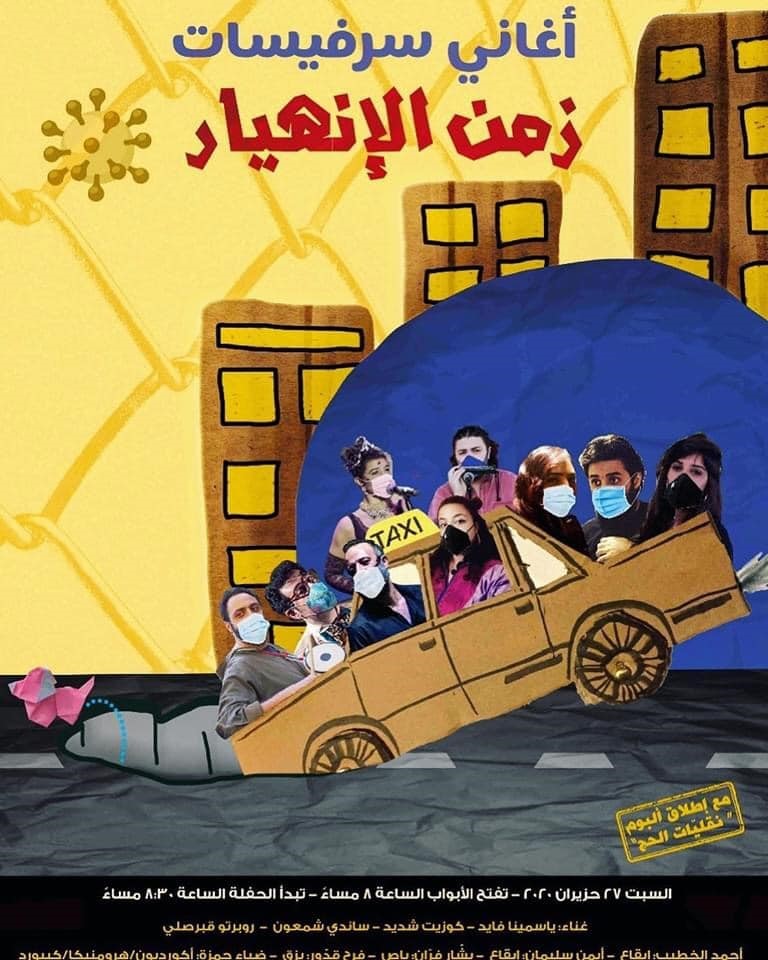

The vigorous rap scene during the October uprising did not completely eclipse other musical genres. Of course, the “classics” were as present and popular as ever, such as Sheikh Imam’s “Build your castles” and Ziad Rahbani’s “What times we’ve reached”. Their cynical nature lives on in the songs produced by Metro Al-Madina as part of a musical project entitled “Service Songs: The Time of the Collapse”, most notably in “Hymn of the Collapse” (written and composed by Hisham Jaber). The song was recorded during a Covid-19 lockdown, using separate recordings by the musicians and singers and making them into an amalgam video.

“The dollar rates destroy the promises of the bank’s governor / in the black market / and even at the airport / It’s a long, long night / or maybe too much daylight / Oh, the excitement! / The collapse is here!” After listing all the violent, revolutionary, retaliatory ways in which the people will revolt against the ruling class, the song concludes that “We had to riot, we never had a choice. Hooray! Here comes the collapse!” Metro Al-Madina’s theater in Hamra Street, Beirut, continued to host evenings of “The time of the collapse” in between lockdowns, while adhering to social distancing and health standards.

Meanwhile, the band members, along with their friends and fellow demonstrators, singers, and musicians, were also regularly performing off-stage, and even blocking the roads with their music. A group led by accordion player Samah Abu Al-Mona rewrote the lyrics to some popular songs and chants to state their ideas and address the people in the streets and banks in their own way. Again, the omnipresent “Hela-ho” manifested in the chant “Hela hela ho, the road is blocked, cuties!”, while Fayrouz's song “Rain, Oh, Sky” became “Block the road, Oh, people. But, if an ambulance comes, we’ll make way!” The lyrics attempted to reassure people about their safety on the roads in the most pleasant way, especially after the media was extremely critical of the frequent road blocks, accusing protestors of “disrupting other citizens’ lives”.

All of the above are fragments and highlights of what was happening on the music scene relevant to the October 17 uprising in Lebanon.

The Visuals of October 17

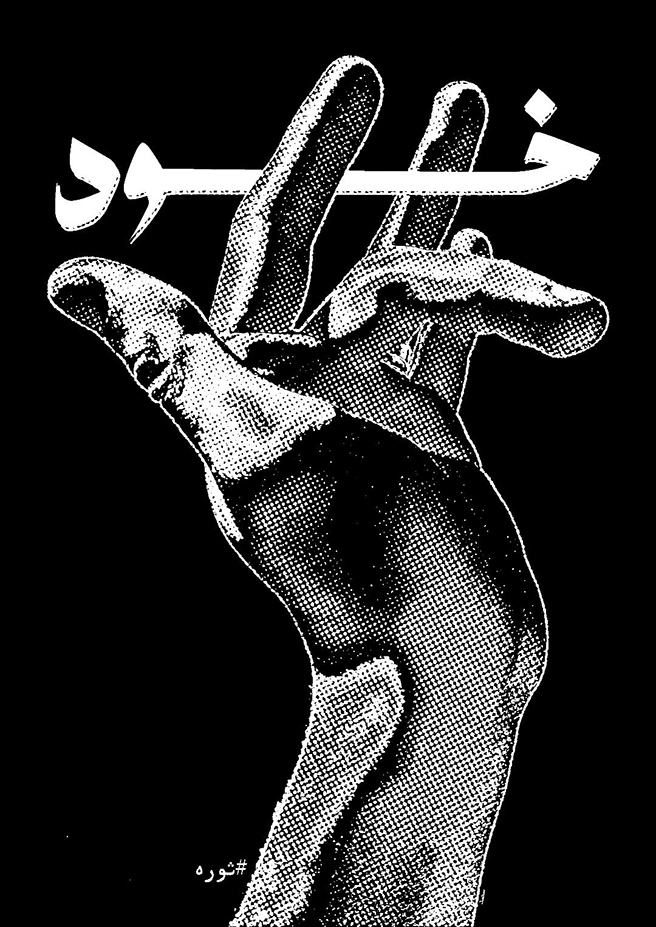

Perhaps the first visual expression that comes to mind when considering the October uprising is the huge installation dubbed “the Hand of the Revolution”, which was erected in the middle of Martyrs Square where the main Beirut sit-in was held. The installation is a giant fist, installed vertically, in black and white, with the word “revolution” printed on it, and it has seen good and bad days since. At first, the fist was the “north star” of the square, which can be seen from afar and acts as a compass that leads the newcomers to the gathering point. A short while later, though, the monument became nothing more than burned debris, after the tents of the protesters were attacked in Martyrs Square and destroyed by a group of supporters of Amal and Hezbollah parties. However, a new fist was installed shortly afterwards, as an expression of the revolution’s resilience against the de facto powers.

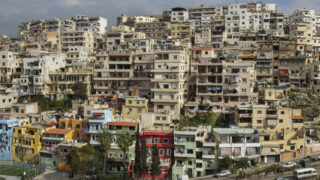

Going for Beirut to Tripoli, for instance, the famous metallic sculpture of the name of “Allah” in the heart of Al-Nour Square stood as a spontaneous focal point to all popular gatherings, and although the structure long preceded the October movement, it still became associated with the protests. It was well lit and taken care of to accommodate the protestors around it, and the building opposite to it was draped by a huge Lebanese flag. Next to it, the words “Tripoli, the City of Peace” were inscribed, as if they were a subtle message that denounced the media’s representation of the city as a warzone and a stronghold for extremist groups.

In the squares across the country, the direct visual elements in the protests were a way of presenting oneself and expressing political stances, rejecting, criticizing, and ridiculing, in any visual display of choice: in clothing, face painting the colors of the flag, drawing up banners, making monumental structures, and of course, in graffiti, too.

The walls of the streets are irresistible blank canvas for a young person with a cheap can of spray paint. They tease the imagination with the unbound possibilities of what can be created on the space that stands before them. It is a possibility that may not exist on another normal day, for there is much to be said during protests. Unlike the fleeting cheers which are momentary and always make way for other sounds to fill the air, graffiti pieces have better chances of staying in a space a little longer, before they are altered or wiped out. World renowned graffiti artist, Banksy, once wrote on a wall “If graffiti changed anything it would be illegal.” Of course, the ironic paradox in his statement is that graffiti is indeed illegal, prohibited by law in most countries of the world, and it is often considered as an act of vandalism. In recent decades, however, it has come to be seen as a political visual medium that stirs and incites. And in a modern world that communicates mostly through visuals, graffiti poses a real threat. It is an unsigned essay and an uncensored painting.

Skimming through the many slogans and chants that were raised in the protests, one can single out some which were truly “trans-regional”. The phrase “everyone means everyone” was certainly the most prevalent of those. Also popular among the protestors was the so-called “Hela-Ho”, a chant inspired by the cheers of football stadium fans, transformed by the protestors into an obscene insult to politicians.

“Our fear has fallen” is one of the phrases sprayed on several walls in the capital city. Beirut is generally a graffiti-friendly city, both during times of popular insurgences and in times of relative calm as well. Enormous murals spread in Ashrafieh, Mar Mikhael, Hamra, and inner city streets, carrying connotations of social and political messages, or simply conveying a certain aesthetic. But during the uprising, the walls were suddenly filled with direct political commentary: revolution, freedom, social justice, condemning corruption and sectarianism, attacking the banks and financial policies, and advocating for women's rights and for the rights of LGBTQ+ persons as well, whose slogans became more visible and explicit - at least in the main parts of Beirut, where the margins for free expression are slightly bigger.

“Resign, now!”, “The revolution is my home”, “Beirut salutes Yemen”, “A revolution against fear”, “Love is not a crime”, “A state of imbeciles”, “Long live the October 17 Revolution”, “When the people go hungry, they eat their rulers”, “Riad Salameh (the governor of the Central Bank) is a thief”, “Leave!”, are just a few of the concise graffiti phrases that say a lot in very few words.

But apart from the phrases that repeat themselves like a mantra in the neighborhoods and on the walls, one finds many elaborate, more symbolic drawings. The overused and hackneyed Phoenix, for example, the Lebanese symbol that has always been conjured in every difficult circumstance or violent event that ravages the country, made a comeback in the graffiti of the October insurgence as well, denoting “a people that does not die” and “rises from the ashes” after turmoil, etcetera. On the other hand, the middle finger was a profusely used symbol as well - at a time when the protestors no longer had any words to say to the ruling class and its gangs in power. They painted the middle finger in murals, hung it up as a poster, and gestured it by simply sticking up their fingers, for the cameras and the world to see.

In a graffiti by artist Rola Abdo, she paints a young face looking at the image of his “homeland”, but one of his eyes is gouged. His eye is an implicit salute of gratitude to the dozens of demonstrators whose eyes were extinguished by the rubber bullets shot by the security forces and riot police.

Other murals depict Lebanese politicians as exaggerated caricatures, naked bodies, or grotesque creatures. Graffiti artist and activist, Salim Mouawad, painted several murals of the “revolution’s bulls”, which are his signature characters that stand for people who reject sectarianism and demand a secular state.

Also in Beirut’s center, close to Khandaq al-Ghamiq, is a huge graffiti drawing by Aya Debs, Ibrahim Tallaih and Youssef Tallaih, depicting a bare-chested young man wearing the famous “Vendetta” mask, with a masked girl at his side. The graffiti revives a phrase that went viral during the 2015 “garbage crisis” demonstrations. It says, “Glory to the infiltrators.” At the time, the demonstrators were accused of harboring rioters and terrorists among them, and that was the pretext used by security forces to use violence in quelling the movements in the street. In the October 17, 2019 demonstrations, the same accusations were made, and the state promoted the idea that rioting infiltrators existed among the “clean” demonstrators, and that the authorities, therefore, had every right to exercise violent restraint over those whom it deemed as “contaminated protestors”.

Graffiti art, as always, was on the lookout, responding to the baseless accusations in “bold” lettering, through arts and popular creations that are both accessible and eye-pleasing. And though the messages on walls reflected varied viewpoints from within the movement, it was clear that the broad stances were unanimous: against corruption, against sectarianism, against plunder…

*****

In the Lebanese squares of October 17, cinematic screenings of critical films were also held, especially in the space of the ancient “Bayda” (The Egg, also known as Cinema City) building in the city’s center, which was destroyed by the civil war and remained an unrestored visual icon that bore witness to the city’s divide. The turnout to the screenings was huge, raising fears that parts of the structure might collapse, so the movie screenings continued in other squares and spaces.

Among the recurrent activities in the squares were open seminars, in which economic experts took turns explaining the ambiguities of the unraveling crisis. In those discussions, anyone could interject and argue in a safe atmosphere that rarely witnessed any disturbances. The tents in Tripoli were particularly active, as they provided a much-needed space for the youth of the city to exchange ideas and ask questions.

Away from the TV screens and the online platforms, the newly discovered gathering spaces where people could watch movies or attend open discussions were alternative “live” platforms that welcomed everyone. Their importance lies in their ability to break from the media’s monopoly as a sole source of information, always broadcasting to the audience as a recipient. Instead, an omnidirectional exchange was now possible.

Everyone had a voice and was able to use it. Sadly, with people retreating to their homes as the coronavirus crisis intensified (along with the exacerbation of the financial collapse), the Lebanese scene now misses a vitality that the squares of the October 17 uprising were able to provide…

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabah Jalloul

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 18/12/2020

1) They are two neighborhoods located opposite one another. Each has a different sectarian majority.

2) “Al Touffar”, the rapper’s self-chosen nickname, is a popular title used in the Baalbek and Hermel region to describe the “outlaws” fleeing from the state, taking refuge in the mountains.