One can say that the “Tunisian Woman,” the modern and emancipated woman, is an image constructed by some heroic Tunisian men who constructed the heroic Tunisian women. One of them was Cheikh Abdelaziz Thâalbi, author of the 2005 book “The Liberal Spirit of the Quran,” in which he advocated for the emancipation and education of women. Another was Tahar Haddad, whose 1930 book “Our Woman in the Shari’a and Society” was overshadowed by the public decision of Manoubia Wertani and Habiba Menchari to take off their veil during a conference about feminism in the same year.

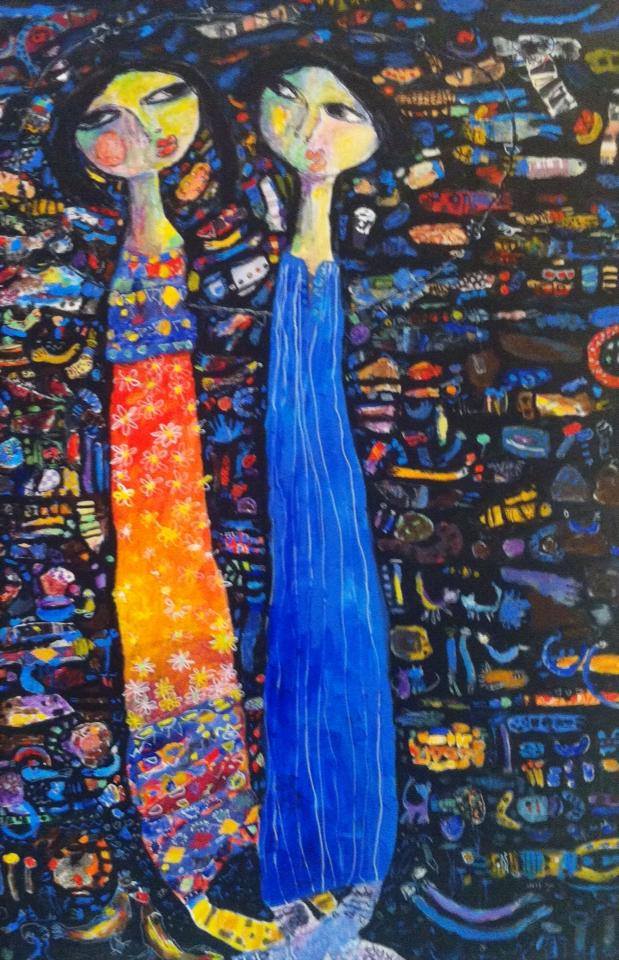

The two reformists, who called for ”women” education and liberation in the nineteenth century, did not view women as diverse and pluralist beings, but rather as a symbol or the figure that carries the symbol. Thus, they emulate other representations of women as symbols, such as Eugène Delacroix’s painting “Liberty Guiding the People,” in which the woman personifies the concept liberty, or Marianne, the symbol of the French Republic. Here, the “woman” personifies the nation, the unity and the unification of different generations. These are precisely the reasons that warrant women education, for women carry the mantle of educating the next generation. All those reformist faces of “women liberation” belong to the classic images expressed by the likes of Rifaa al-Tahtawi or Qassim Amin.

As shown by the title of Tahar Haddad’s book, “Our Woman,” it is men have to take care of “their” women.