Executive Summary

Yemen’s local councils are responsible for the day-to-day provision of basic public services to 26 million Yemenis and are amongst the most crucial institutions of governance in the country.

However, the outbreak of civil war in 2014 and the subsequent Saudi-led military intervention in Yemen in March 2015 has devastated local councils’ ability to provide these services: financial resources have evaporated, armed militias challenge their authority, and extremist groups such as Al Qaeda and the Islamic State have assassinated council members. Despite the challenges, local councils have been generally resilient and continue to operate in some form in most parts of the country, though they have been rendered ill-equipped to handle the largest humanitarian crisis in the country’s history.

This paper assesses the historical context through which the local councils came to prominence, their role in decentralization and governance, the challenges they have faced through the uprising and civil war, and their essential role in any negotiated cessation of hostilities and post-conflict reconciliation. This paper will examine why it is critical for the international community to coordinate with and channel humanitarian support through the local councils, given that this would help alleviate widespread suffering, help sustain this crucial form of governance in Yemen, and prevent jihadist groups – most notably Al Qaeda – from exploiting gaps in basic services to garner support.

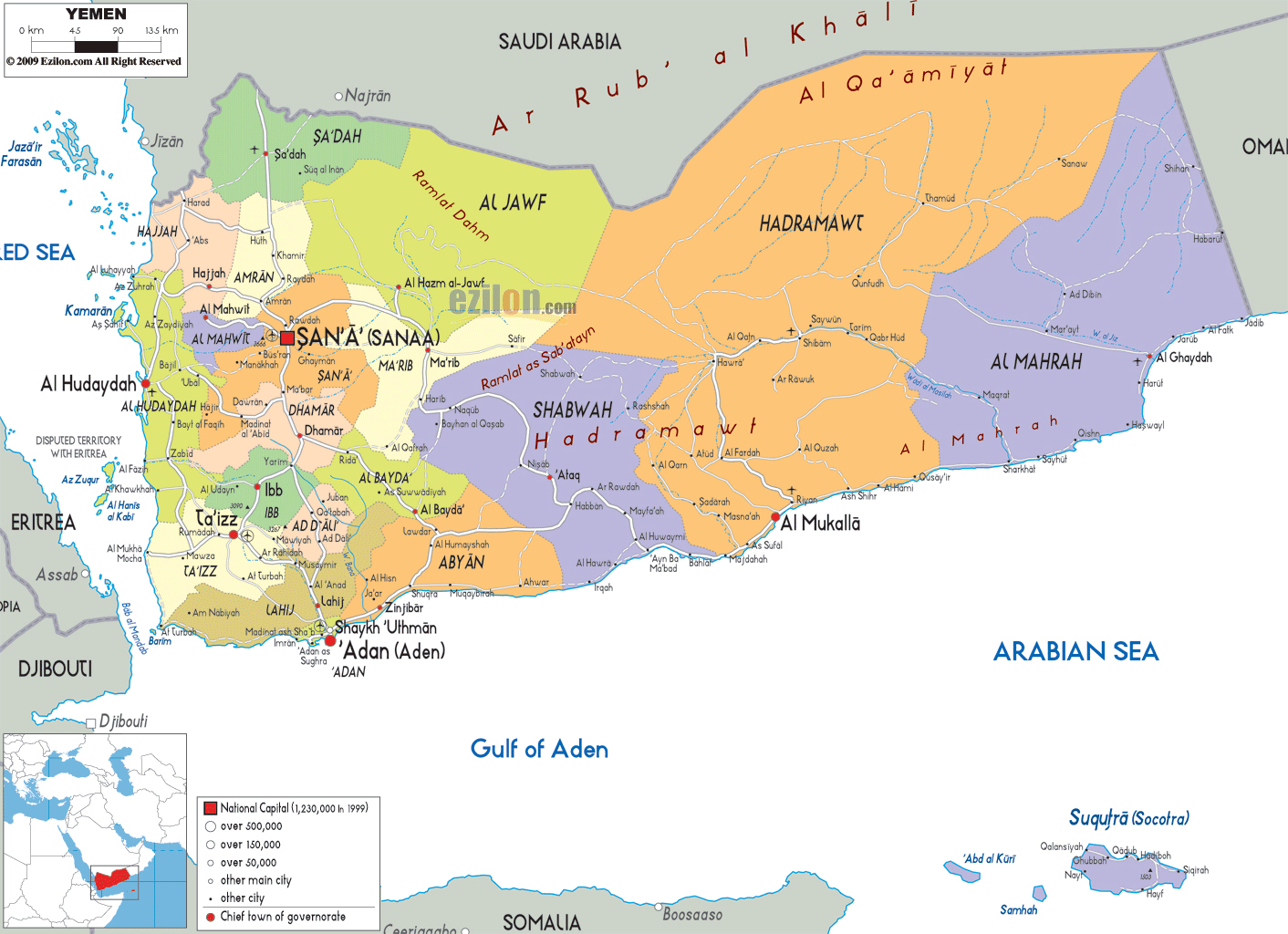

To provide a balanced view of the challenges facing local governance in Yemen, this paper focuses on three specific areas of the country: Sanaa, which is currently under the control of the Houthis and their allies; Wessab, in central Yemen, currently controlled by local councils in coordination with the central government in the capital; and Aden in South Yemen, currently under the nominal control of the internationally recognized government.

The foundations of local governance

Political pressure for the decentralisation of power began to build following the 1994 civil war between North and South Yemen; the south lost the war, but the general desire for more local autonomy remained, and gained impetus following changes to central government administration enacted in 1998. These changes divided the country into provinces – called governorates – with each governorate subdivided into districts. The central government in Sana’a appointed the directors to head each district, with these directors reporting to the governor of the governorate, also appointed by and reporting to the central government. As a result there was, for all intents and purposes, no local representation in local governance, with all power and decision-making authority centralised in the capital.

The district directors and governors in the south, and indeed across the country, often came from either the capital, Sana’a, or Sanhan, the home village of then-President Ali Abdullah Saleh in the north. These officials would arrive with little connection with the area they were responsible for and often spoke a different dialect from local residents. This created significant challenges for effective governance and, as locals often refused to cooperate with these perceived outsiders, contributed to an already destabilised security environment. One clear result was the growth of movements in the south calling for the federation of Yemen, or even complete secession from the north.

The local councils’ law, issued by the central government in 2000 and implemented in 2001, was meant to neutralise federalist and secessionist movements and alleviate the political pressure on the central government. This law laid the blueprint for the creation of local councils – essentially municipalities – and the decentralisation of many central government powers to these new entities, with the central government maintaining legislative authority over areas of national policy, such as foreign relations, the military, and security.

Article 9 of the local governance law states that local councils are to be freely and directly elected by the citizens of the area, who also have the right to run in these elections themselves. When citizens went to vote they were given two ballots: one was to vote for the candidate to represent their area to the district level local council; the second ballot was to vote for the representative of their district to the governorate level local council, with the governor being the head of both the governorate council and all district level local councils within the governorate.

In the first local council elections in 2001, there were 7,032 representatives elected to both district and governorate level local councils across the country. Article 13 of the local governance law set their term at four years unless, due to a force majeure, new elections could not be held, in which case the existing local council would remain until a new ballot was possible. The second round of local council elections were held in 2006 in parallel with the presidential elections, with constitutional changes that year extending the local councils’ mandate to six years. Due to the security situation in Yemen, however, local council elections slated for 2012 have been repeatedly postponed, such that the council members elected in 2006 remain in place today.

Limits to local power

Before local councils existed, all government functions related to the day-to-day running of society, such as education, health, water and sewage provision, waste collection, roads, electricity, tax collection, as well as the ability to allocate resources and initiate development projects, were run through the centrally appointed directors’ offices, where even the staff had to apply for their jobs in Sana’a [1].

The local councils’ law of 2000 was effective in decentralising many aspects of central government power, with local councils taking on responsibility for essentially all government functions related to the day-to-day running of society, as well as the ability to allocate resources and initiate development projects. This authority to implement decisions, and the local councils’ direct accountability to the population at large, quickly made them among the country’s most important public institutions.

However, the president and the central government maintained veto power over all local actions, due to the fact that the areas of local jurisdiction weren’t explicitly stated in the local governance law, and the governors – who head all the local councils within their governorate – continued to be appointed by, and were subject to the decisions of, the central government and ultimately the president. An amendment to the local councils’ law in 2008 allowed for governors to be elected by local council members at both the district and governorate level. This did indeed happen that year; however, President Saleh overruled several of the election results – most notably, in the provinces of Saada and Al-Dhale. Since 2011, and despite the 2008 amendments, governors have been appointed by presidential decree.

The budget mechanisms

Local council revenues come in the form of block funding from the central government, local taxes and fees, and support from external donors. Central government support is distributed to governorate level councils based on an annual assessment of criteria such as the ability to raise funds, population density and growth, poverty rates, and the local administration’s previous performance in the collection and expenditure of funds. Governorate level councils then distribute these funds to the district level local councils according to similar criteria.

Locally raised revenues consist of fees added to service bills – such as electricity, water and phone – taxes on commercial activities such as advertising, and a proportion of the tax revenue the local council collects on behalf of other levels of government. Governorates that enjoy strategic resources, such as Hadramaut, Mareb and Shabwa where oil and gas are extracted, have no claim to resources in their areas. Revenues from such natural resources are collected locally but distributed centrally by the authorities in Sana’a. In practice, due to rampant corruption, revenue collected by Sana’a far exceeds that redistributed.[2] Local councils in areas with significant natural resources, such as oil, gain only indirect benefit in the form of donations, development projects and local employment facilitated by foreign oil companies, who regularly undertake such endeavors to win over local support for their operations.

The local governance law also allows local councils to obtain financial support from external donors. However, this support is meant to be facilitated through the central authorities, with the branches of the Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation (MOPIC) in each governorate overseeing the process of obtaining external support.

The budgets dictating revenues and expenditures in each district local council are developed through each council’s executive office, which calculates the expected revenues from the various sources and then sets expected expenditures for services and development according to localised priorities.

The annual budget is discussed among the entire council to obtain the council’s endorsement, at which point the governor passes all the district level budgets to the governorate level local council’s planning and budget commission. Here all the district level budgets are collated into a single budget for the entire governorate, which the governorate level local councils discuss and endorse, allowing the governors to present their budgets to the Ministry of Local Governance and the Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation, which incorporate them into the national budget to be approved in the Parliament.

It should be noted that despite the final budgets being approved in the Parliament, governorate and district level local councils have been chronically underfunded given that the resources the central government distributes to the local councils regularly falls short of their budget requests.

Local governance during revolution and war

The nation-wide uprising in 2011 and ensuing political crisis became a force majeure which rendered new council elections in 2012 impossible. The crisis persisted, and then deteriorated markedly in 2014 when Houthi fighters, allied with forces loyal to former President Saleh, took control of Sana’a. These events precipitated a full blown civil war and the Saudi-led international military intervention of March 2015, all of which have continued to derail new elections. Today, the local council members elected in early 2006 remain in place.

Given the local councils’ role in governance and their importance across the entire population, opposing political forces in Yemen have competed for influence over the councils and their members. For the political parties, controlling the local councils means controlling decision-making in the directorates, while the local councils also offer a means to mobilize rural Yemenis – previously to join the protest movement, and more recently for military recruitment on behalf of the political factions.

Post 2011, the struggle for control over local councils weakened their administrative capacity and hampered their ability to carry out the daily functions of governance. Their work was also hindered by the tension and general polarisation of society that took place during the next three years of political crisis, which lead to the eruption of widespread armed conflict. Political authority during this period was technically in the hands of the transitional President, Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi, who took over after Saleh’s departure and was able to replace a number of officials at the gubernatorial and directorial levels. That being said, the General People’s Congress (GPC) party, which remained largely under Saleh’s sway, maintained effective control over much of Yemen’s local governance, particularly directorate level local councils in the Yemeni highlands, where pro-Saleh tribal figures dominated.

The impact of war on local governance

Following the Houthi movement’s military takeover of Sana’a in September 2014, the ability of local councils to provide services and govern weakened substantially, as their sources of financial funding, as well as the wider economy, began to collapse. The severity of the crisis was magnified exponentially after the Saudi-led military intervention in March 2015. Local councils in Sana’a and Taiz, for example, have seen financial resources siphoned off by the Houthis for use in their war effort. Unlike most areas under Houthi control, however, the capital’s local council is still holding meetings and able to supervise and administer a reduced level of service delivery within the city; outside the capital, most local councils in areas under Houthi control now operate with limited decision making capacity only, given that the Houthi group has supplanted their autonomy by appointing its own supervisors in the directorates. Though these supervisors officially work within the framework of the directorate’s local council, in practice they represent a parallel governance structure. Notably, however, these Houthi appointees have by and large not exercised their authority to implement substantial changes to the functioning of the local councils, but rather allowed the previous bureaucracy and staff to continue on in their duties with minimal interference, albeit within a markedly more difficult financial and security environment.

In the city and wider governorate of Aden, from which Houthi military forces have retreated and Hadi’s internationally recognised government has reasserted a degree of control, the local councils have been able to retake some of their former responsibilities. It is important to note that these district level local councils continue to coordinate through the governorate local council, continue to submit financial income to Sana’a and receive funds in return from the central government, though these are now essentially limited to paying employee salaries. In areas under the control of the internationally recognised government additional resources are being made available to local councils via members of the international coalition backing Hadi that do not go through the Sanaa, though this foreign aid – most notably from the Emirati government – has almost wholly avoided cash disbursements, and instead focused on infrastructure and redevelopment, such as the provision of power generators and the rebuilding of government offices.[3]

Security and service delivery

In many so-called “liberated” areas the local councils have faced various obstacles. Many anti-Houthi resistance militias continue to have a significant footprint and are unwilling to hand power over to civilian control. There are also security-related challenges due to the proliferation of arms and the power of the radical groups. Notably, Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and the Yemeni branch of the Islamic State (IS) group have targeted security personnel and local council members. In December 2015, jihadists assassinated Aden’s then-governor, Jaafar Mohamed Saeed, and they have repeatedly targeted the current governor and the city’s security director. The general security situation, and direct threats from extremist groups, has left directors of various directorates unable to travel and monitor the areas they are responsible for.

At the same time, jihadist groups have aimed to take advantage of the gap in basic services to garner support from locals. In Mukalla, where AQAP governed for more than a year before the city was retaken in an Emirati-led military offensive, the group provided electricity and medicine, engaged in infrastructure projects, and even dealt with disaster relief in response to Cyclone Chapala.

Current budget support and revenue

One of the key challenges for local councils is the lack of public funding. Since the beginning of 2015, no new budgets have been endorsed. Currently, as per orders from the Ministry of Finance, governorates and other local authorities are operating based on their 2014 budgets – the last ones endorsed by parliament. The central government’s financial support to the local councils was then cut in half in 2015, with the councils being directed to maintain only the most basic of operational costs.

Even this reduced level of central government funding to local councils is not guaranteed and constantly disrupted. For instance, in the Wessab directorate – which has stayed effectively neutral during the war – the local council previously obtained in the range of 150 million rials per year in central support; this has currently dropped to between 20 to 30 million rials. [4] Income from local sources – such as taxes and fees – that previously brought in between 50 to 100 million rials per year has also dropped roughly 70% due to the economic fallout of the war. [5] The local council at the directorate of Tawahi, in Aden, used to obtain annual central government support amounting to 360 million rials; as of March 2015, this support has stopped completely. [6] Locally raised revenues from residents and businesses in the district have all but evaporated, leaving the Tawahi local council’s sole source of funding the 120 million rials the Aden governorate level council has been able to supply. In areas rich in natural resources, such as Hadramaut, Mareb and Shabwa, the security situation has forced international oil and gas companies to halt production, resulting in a corresponding fall in indirect forms of financial support.

Such massive losses in funding would have devastated government service provision even in peacetime, but in light of the ongoing conflict and collapse of the private economy, the resultant humanitarian crisis and widespread damage to infrastructure, local governance structures across the country have been rendered unable to provide most basic public necessities, just when Yemenis – particularly in rural areas – have never been in greater need.

Involvement in hostilities

Local councils have played a variety of roles in the conflict. On a positive note, many have helped mitigate the impact of the war. In the Ibb governorate, located in the middle of the country and the effective geographic center of the conflict, local councils have managed to mediate numerous local ceasefires, facilitate the movement of basic commodities and humanitarian supplies across front lines, and orchestrate prisoner exchanges, among various other agreements between the warring sides. Local council leaders such as these, who managed to maintain their neutrality and good relations with local groups on either side, will play a crucial role in post-conflict reconciliation. Their awareness of the social intricacies of local areas is also an expertise the central authorities largely lack.

In many instances local councils have played a decisive role in determining the outcome of battles in favour of one side or the other. While in Hadramaut local councils played a critical role in liberating the area from AQAP, which had controlled the capital of the governorate for more than a year, in many other instances local councils and their members have succumbed to the polarizing effects of the war. In Aden, for instance, the local council played a crucial role in expelling Houthi fighters and allowing coalition-backed forces to take control of the city, after which the local council began the process of reasserting its role in local governance; interestingly, a number of government buildings were handed over to local council officials by local resistance forces, underlining the willingness of some armed groups to cede power to local institutions. In other instances, the conflict has divided the local council against itself. In the Al-Hujariah region of Taiz governorate, where local council members took up arms, some joined the Houthis and others fought with the internationally recognised government.

Humanitarian crisis response

The scale of the humanitarian crisis in Yemen is catastrophic. In June 2016 the United Nations reported that “more than 13 million Yemenis are in need of immediate life-saving assistance”, with almost three million people becoming internally displaced. [7] The enormity of human suffering has far exceeded the capacity of domestic authorities to address on their own. Another serious challenge has been the general lack of electricity in the country – the Mareb power plant, which feeds the national grid, began failing in 2014, and collapsed completely in 2015 – while the widespread fuel shortage has rendered generators inoperable. The lack of fuel has also hobbled transportation networks and led to a general inability to pump or transport water, resulting in crop droughts, a drastic decrease in public waste control and sanitation, and an increase in public health disorders.

The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and UNICEF are the two organizations leading the wider international humanitarian response, which has included providing aid directly to IDPs, and at other times via local councils. In regard to how the UN has intervened when local councils lost the ability to provide for the local population, a good example came in April this year, when 2.1 million people regained access to a reliable source of water after fuel was supplied to the local water companies in eight governorates: Sana’a, Al-Hadida, Omran, Hajja Saada, Abyan, Lahij and Ma’rib. UNICEF has supported the implementation of a sewage treatment facility in the capital, which benefitted 1.4 million people, while also providing fuel for power generators in several major public hospitals, thus ensuring that they continued providing healthcare services. [8] All of this was done in coordination with the local councils, an arrangement that facilitated the delivery of aid, alleviated large scale human suffering, and help maintain the functional capacities and public legitimacy of the local councils as the state’s primary service provider; even in instances where foreign organizations delivered aid independent of the local councils, the successful delivery of that aid has depended on a minimal degree of coordination with the local councils.

Looking Ahead

Expected role in federation

Local councils are expected to be a significant component of any negotiated settlement to the conflict in Yemen. It is widely expected that any resolution to end the hostilities will include some form of federation of the republic. Even while the specifics of what that federal system might look like remain unclear, in general, it can be expected that the new federal organization will not override the present structures of the local councils but rather develop and enhance their jurisdiction at the expense of central government authority. The likelihood of this is supported by the fact that at the national dialogue conference between Yemen’s major political powerbrokers that took place between March 2013 and January 2014, (prior to the outbreak of major hostilities), preliminary discussions regarding federalism reached a general consensus that the smaller units of the federal territories would have a greater role in decision making than both the federal territory they belonged to, and the central government.

That said, the precise borders and administrative divisions of the local councils in the border areas between the different territories can be expected to remain a contentious issue in the negotiations; parties in southern Yemen have long accused the central government in Sana’a of dividing governorate districts in such a way as to tilt the balance of power in favour of the north, and to dilute the southern identity of areas that had classically been considered part of the south.

International role

Even with a negotiated settlement between the main parties in Yemen, the challenges to peace are myriad. Political polarisation has fueled unprecedented regional and sectarian divisions. The erosion of the state has prompted a security vacuum through which groups like Al Qaeda and Islamic State have established unprecedented footholds in the country, while new militia-based power brokers are asserting authority through arms. Such groups are also able to capitalise on high unemployment and the absence of effective state-backed social support networks in order to recruit and radicalise. All this, in conjunction with a massive depletion in financial resources, is greatly hindering the ability of the local councils to carry out their primary mandate of providing basic public services, or in responding to the deepening humanitarian crisis the war has created – a crisis that grows more severe by the day.

It is crucial that the international community’s humanitarian intervention in Yemen be tailored to empower local councils to provide basic public services to Yemenis, until such time as they are able to return to a domestically sustainable model of financing. This intervention must take into consideration the need for transparency and accountability mechanisms, and ensure that the aid does not become overly politicised in favour of any side in the civil war.

In Syria, international donors have supported similar interventions, such as the United Kingdom and European Union-backed Tamkeen programme, which funds the delivery of basic services and provides technical assistance to local councils as a means of promoting stability, good governance and preparing for a long-term peace settlement. The results have supported improved water and electricity provision for hundreds of thousands of Syrians, as well as healthcare and education services.

The international community coordinating with, and channeling support through, the local councils will serve a variety of positive outcomes, including alleviating the humanitarian crisis through locally provided solutions, kick-starting economies so basic markets can function, and most crucially, maintaining the institutional structures that will likely play the most significant role in post-conflict reconciliation and reconstruction when a settlement is finally reached.

Yemen is fragmenting as a result of the current conflict. Whatever the final negotiated settlement – given the unlikelihood that any side will achieve a decisive military victory – the ability for local councils to survive the conflict, help implement the agreement, and provide basic public services will be crucial to future stability of the Yemeni state. If Yemen’s local councils are allowed to fail and dissolve completely, there will be no official governance across most of the nation; Yemen, as a state, would effectively cease, with the most likely result being that the catastrophe the country is facing today paling in comparison to what emerges tomorrow.

This paper was made by Adam Baron,Andrew Cummings,Tristan Salmon, and Maged al-Madhaji and was first published by published in both Arabic and English by Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies in partnership with Adam Smith International

Notes:

*The authors thank Farea Al-Muslimi for his editing, review, and feedback to this paper.

[1] The Social Fund for Development (SFD) was one of the few examples of a successful development program that ran projects around Yemen separate from these local offices. SFD independence from central government procedures and in some cases direct partnerships with locals helped support its delivery – although this was also done independently from local councils.

[2] For more, see https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/files/chathamhouse/1011pp_yemeneconomy.pdf

[3] Interview, local government official, Aden, July 2016.

[4] Despite prolonged political turmoil and armed conflict, the Central Bank of Yemen had, until recently, successfully kept the official value of the rial stable against the US dollar, with the official exchange rate not deviating significantly from the black market rate. Thus, the central government funding the Wessab directorate had previously received (150 million rial) had been equivalent to roughly US$700,000; due to a drop in the value of the rial in the spring of 2016, however, the reduction in central government funding for Wessab has been magnified in real value terms, with 20 to 30 million rials now equivalent to US$80,000 to US$120,000.

[5] Interview, local government official, Wessab, July 2016.

[6] Interview, local government official, Tawahi, July 2016.

[7] According to an Integrated Food Security Phase Classification report regarding Yemen, published June 14, 2016, “Escalated conflict, restriction and disruption of commercial and humanitarian imports, population mass displacement, loss of livelihoods and income, scarcity and high price of fuel, disrupted market system and high price of food and essential commodities, suspension of safety net and public works programme that used to serve 2.5 million people contributed to the widespread food insecurity and malnutrition. The conflict damaged the public and private infrastructure; destabilized the market system and prices; negatively affected employment opportunities and income and devastated livelihoods, exposing millions of the rural and urban population to destitution and food insecurity. About 51% of the population is suffering from food insecurity and malnutrition…” http://www.ipcinfo.org/ipcinfo-detail-forms/ipcinfo-map-detail/en/c/418608/

[8] These include Sanaa’s Republican Hospital, Al-Thawra Hospital, and the Al-Sabaeen Mother and Child Hospital.