This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

On that day around the end of 2019, I was taking a walk with a friend of mine, the poet and painter, Muhammad Thamer Youssef, when party members, militia men, and kidnappers attacked with horrific, intolerable violence, Tahrir Square and its youth who dreamed of a better Iraq.

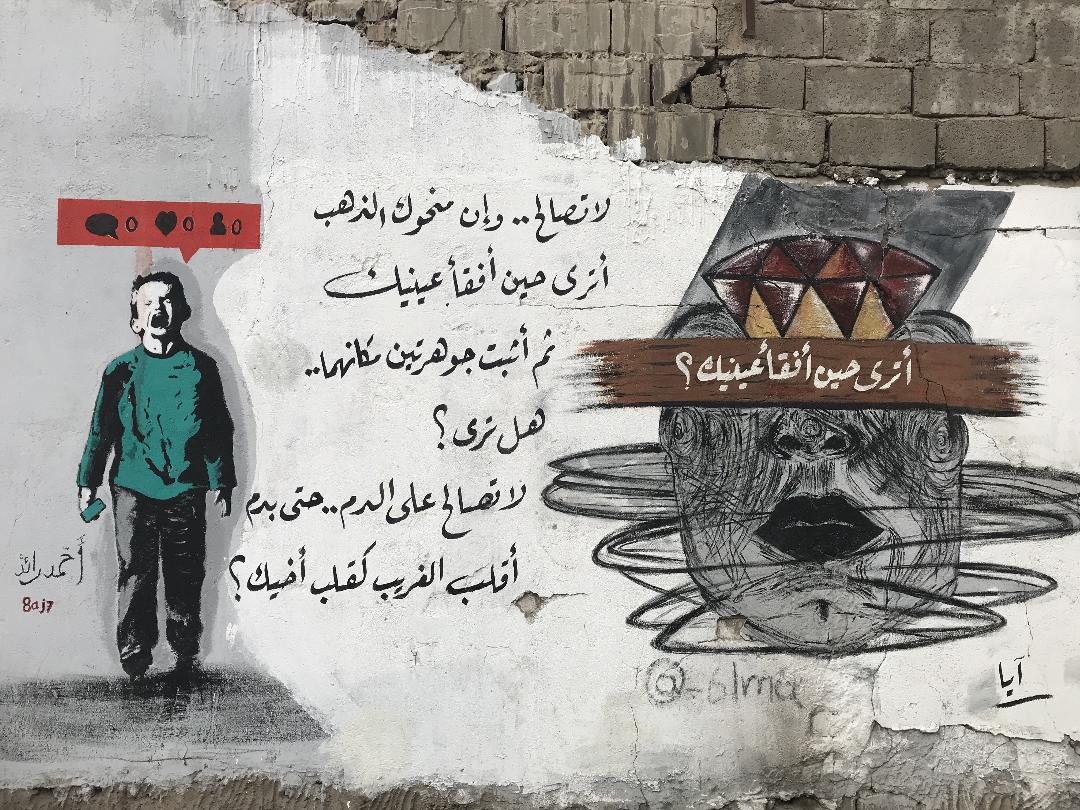

Our tour had started at the Tahrir Tunnel and continued to al-Rasheed Street. Along this route, spaces of color and free expression appeared and spread in every direction. Baghdad had never seen such a peculiar artistic lineup in the city that has for so long been drowned in the photos and banners of politicians and clerics.

As soon as we reached the entrance to Tahrir Beach, which branched from al-Rasheed Street, we laid eyes on a young artist busily completing a painting of his. Without any introductions, this dialogue ensued:

- “Do you ever think about the fate of these drawings after the movement ends?”

- “What we’ve been doing is an expression of an existential moment, in which we declare who we are and announce our rejection of all those who wish to eliminate independent thinkers who aspire to break beyond the walls of this new authoritarianism.”

The young man was aware that the protest movement was also a platform for unleashing his talent. He was able to leave his mark in a previously untouchable public space; one which had always been dominated by the faces and slogans of politicians and religious leaders.

Spontaneous and casually dressed

There was a sort of spontaneous organization which governed the graffiti painting activities that emerged in an urgent moment of revolutionary confrontation. The artists organized as a group whose members knew and respected the unseen borders between their zones in the exquisite artistic haven of the Tahrir tunnel. The well-coordinated, colorful spaces seemed to have escaped the country’s history of ever-bleeding wounds. We were standing before an eclectic art exhibition which had no formal curator, which waited for no government official to come and cut a red ribbon at its opening, and which presented artworks of people who did not seek to join any petty competitive art market.

Perhaps it was one of those rare moments in which amateur painters and professionals worked side by side, with neither personal nor public tensions or condescendence, in both offline and virtual spaces.

The tunnel and some of the walls of Tahrir square were adorned by diverse works of art. Since the beginning of the popular insurgence in October 2019, the youth reclaimed public spaces as entirely their own. They felt free, for the first time, to express themselves outside the confines and rigid rules of a city that never listened to their voices. One painting after another, a comprehensive art gallery was taking shape. It exhibited various styles of artistic expression, both professional and amateur, turning the area into an improvised artistic district, ruled by no other than those adventurous, casually dressed, and colorful artists.

Paintings remain while “delivery” activism vanishes

In its essence, the explosive energy of Iraq’s youngest generations was a temporary release from the feelings of disappointment they have always experienced, growing up in a world which brought them no comfort. They compared the lives they knew with what they saw on social media websites or in the cities they had visited for several days with their families in the east and west of the country, and thus, they have experienced a deep cultural shock that grew bigger and angrier until it exploded in public outrage that spilled onto the streets.

On the destiny of the street paintings, a young artist says: “What we’ve been doing is an expression of an existential moment, in which we declare who we are and announce our rejection of all those who wish to eliminate freethinkers who aspire to break from the walls of a new authoritarianism.”

The visual artistic expressions did not leave the chants of demonstrators alone in the battle against the existing forces. Rather, the arts acted as an embodiment of the various imaginative forces that found in the walls of public spaces a perfect medium of expression and a unique aesthetic foundation for a community that belonged exclusively to that revolutionary moment in October - far from the formal patterns and known cultural and artistic entities. As death was being declared in the squares, a counter statement had emerged in the face of the bullets that looked for fresh bodies inside whom to extinguish their fire. The art works were not only a response to the elimination of young people from life itself, but also a bridge towards truth, which had a moral value at the time, and a potential to create real impact in the future that remained.

Not only did the Tahrir Tunnel create artistic connections on the ground, but it also spread its soft action to other squares south of Baghdad. It creatively influenced other spaces, not by acting as a center while the other squares in neighboring provinces were merely margins, but rather by virtue of the fraternity, mutual cooperation, and creative networks that harmonized action in the various squares for the sake of consistency and unity.

Many accusations have been made in order to raise skepticism regarding the spontaneity of the majority of the activists who were part of the October movement. Some did not believe the emergence of a new generation that rejected the entire logic that governed Iraqi political life post-2003; one which affirmed the power of sectarian bodies over public life, daily dealings and public employment. Those who believed that an elegy for sectarianism was yet to be written, and those who were only able to see things through the “us and them” binary, all questioned the intentions of protestors. Their rejection reached the point of blaming every problem, big or small, on the young protestors. An observer remarks: “The various forces and parties in Iraq have always condescended the people in their societies and have even been relieved by the apparent state of loss that their societies lived in. With the popular insurgence, the protest groups grew more estranged than ever from all politicians and their cronies.”

The tunnel leading to Tahrir Square was transformed into an art gallery which had no formal curator, waited for no government official to come and cut a red ribbon at its opening, and presented artworks of people who did not seek to join any petty competitive art market.

There is no denying that the squares of protest have indeed been infiltrated by some “paid” tents and mercenaries who would spread slogans and mobilize for the benefit of their specific operators. However, their presence did not eclipse the greater brightness of the movement, as documented by the photographs that showed thousands of honest faces. There is no doubt that the painters and graffiti artists were there, at the forefront of the October protest movement and its environment. Their works were still there after the many “paid” tents were removed, outliving the “delivery” activists who had impure intentions. The scene and what it meant was reminiscent of a quote from the novel “A Feast for the Seaweeds”, by Haidar Haidar. The phrase might as well be inscribed into the temples of that tunnel in Baghdad: “History is like the sea. In a moment of anger, it expels algae and the ruins of pirates from its guts onto its shores, yet the sea remains.”

The tunnel with its many drawings was that clear sea of revolutionary movement in 2019. It manifested the desire to create a fully-comprehensive exemplary model, uncontrived, and tangible, from the heart of Baghdad… It was a model that stood against the death of the state and its failure to rise, and sought to disillusion Iraqi society from the mirage that trapped it in dream after dream, only to discover that it is hostage to repetitive news about a political project which was founded on terrorizing the people and inciting them against each other.

Female-signed graffiti

Much of the graffiti work around the world has been signed by anonymous artists with pseudonyms. Painting on a public surface was their way of sending out a message to the authorities, or even to their own societies. In our Iraqi case, individual intellectuals and artists - myself included – have engaged in experimenting with consolidating the presence of graffiti art in the Iraqi public space. The works were left for the street-dwellers’ consideration, with some of them showing illustrated faces of creative local figures or quotes from poems which condemned the tribal vengeance wars

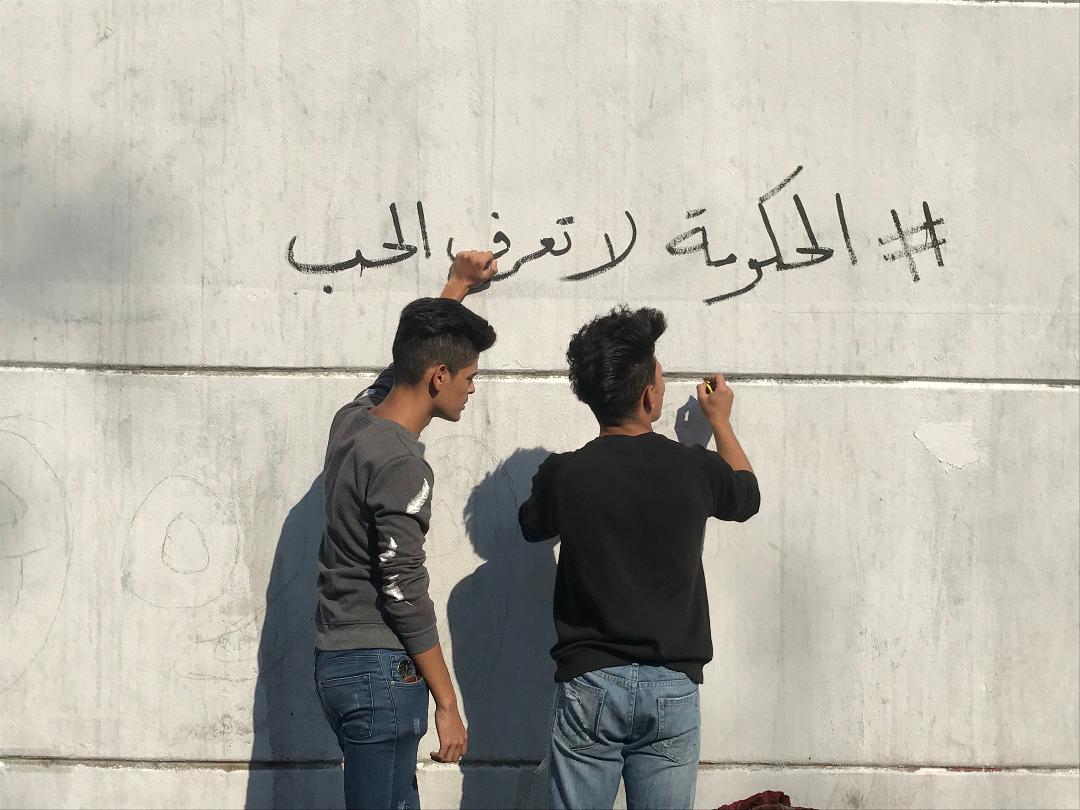

Nevertheless, during the October revolution, things were different. The graffiti artists who painted the weapons of snipers and the oppressive authority figures did not shy away or hide. On the contrary, they were braver than most, as they were also the demonstrators who held the sit-ins and stood in the squares for hours throughout the days and in the darkness of the nights, completing - with their drawing tools – the features of those stalking and persecuting them.

Nevertheless, during the October revolution, things were different. The graffiti artists who painted the weapons of snipers and the oppressive authority figures did not shy away or hide. On the contrary, they were braver than most, as they were also the demonstrators who held the sit-ins and stood in the squares for hours throughout the days and in the darkness of the nights, completing - with their drawing tools – the features of those stalking and persecuting them.

Pre-October graffiti was an individual practice that was carried out within initiatives, and artists used to sign their works using a visual symbol or their initials. In the new “October Republic”, the graffiti artist would write her name next to her male colleague's. Others took pride in making their names visible on the walls of the tunnel. The graffiti here are not only defiant and symbolic of the impossible dreams, always liable to the possibility of being annihilated, but they are also feminine, created by females as much as they were by their male counterparts and colleagues. Those artists had more to offer to the movement than the traditional and standard descriptions of a “soft” participation in protests.

From Al-Habboubi to Nahawand

The tunnel’s graffiti art in Baghdad was not the only aspect of the youth’s expressive energy, but perhaps a central starting point as well. About 360 kilometers to the southwest of Baghdad, Nasiriyah can be considered the main ground for a special kind of social confrontation with the political parties, which goes beyond the act of demonstrating alone, to formulating phrases and writing banners that quickly spread from Basra to Baghdad. What else could one expect from a city known for being a cauldron boiling with colloquial and standard Arabic poetry, and famous for spreading ancient words of wisdom.

In the new “October Republic”, the graffiti artist would write her name next to her male colleague's. The graffiti here are not only defiant and symbolic of the impossible dreams, always liable to the possibility of being annihilated, but are also feminine, created by females as much as they were by their male counterparts and colleagues.

The city of Nasiriyah as a field of protest was an image of a special kind of social break with the authority, carried by the language and voices of its own people who had been waiting for a long time to get rid of that bitter taste of oppression in their mouths.

“A sit-in in Al-Habboubi Square,” “an explosive device found near Al-Habboubi Square,” “The chants of Al-Habboubi Square today…” In those days, this was how all the news from Nasiriyah sounded, with “Al-Habboubi” always in the spotlight. It wasn’t odd that the name of the square honored Mohammad Said Al-Habboubi, the Iraqi poet and scholar who had expressed his rebellion in his poems and throughout his life.

The city of Nasiriyah, about 360 km to the southwest of Baghdad, a cauldron boiling with colloquial and standard Arabic poetry, and famous for spreading ancient words of wisdom, showed an image of a special kind of social break with the authority, carried out by the language and voices of its own people who had waited for so long to get rid of the bitter taste in their mouths.

In the square, where the poet’s statue stands, and where poetry and linguistic expression seeps from every corner, we discovered “Nahawand Turki”, the bravest female voice in the province. She is a young woman who became known for writing and reciting her popular revolutionary poems that give momentum and support to the revolution, raising the protestors’ spirits so that they could carry on.

The cheers and poems of Nahawand and the tens of women around her were an unfamiliar sight in the south of Iraq. The young woman was living proof of an entire society’s vitality, but also, particularly, of its women’s ability to wage a noble and decisive confrontation, even if it seems suicidal, knowing that Nahawand and others are susceptible targets for bullets, which they only escape by strokes of luck.

“Nahawand Turki” was the bravest female voice in the Nasiriyah province, known for writing and reciting her popular revolutionary poems that gave momentum and support to the revolution. The young lady was living proof of an entire society’s vitality, but also, particularly, of it women’s ability to wage a noble and decisive confrontation, even if it seems suicidal.

On mobile phones, many video and voice clips of the protest cheers went viral. “They claimed we’d be bored after a few nights of protest, yet we’re not / They’d burn our tents so we’d go home, yet we won’t;” “This city is a symbol of sacrifice, this here is Nasiriyah/ This city is the home of martyrs, this here is Nasiriyah;” “Let all the parties hear/ We are a steadfast generation/ Your threats don’t shake us/ We are a steadfast generation.”

Karbala and Najaf: new visual motifs

No serious effort was made by the media and television channels to dig deeper in search for different scenes in the various Iraqi cities. While everyone is well-acquainted with the Ashura mourning rituals in Karbala and its traditional identification with the epic-tragic theater, we know very little about the relationship of the new generation in Karbala to plastic arts and modernity. We don’t know, for instance, how the youth interacts with or shows appreciation for the image, taking into consideration that visual data and expressions will be the building blocks of this generation’s historic memory.

It is said that “man is a descendant of the sign,” and the sign is a descendent of painting and drawing, so in a city like Karbala, which is laced with the voices of the religious platforms and mourning recitals, it was remarkable to witness the emergence of some young people who painted powerful, well-worded graffiti slogans in the midst of the demonstrations. Their work bewitched the passers-by and prompted them to interact with it, make interpretations, and communicate with others in the movement across the borders of the city and towards Baghdad, Nasiriyah, Basra and others.

And in Najaf, another Iraqi city stereotyped by the media as a religious center with a one-dimensional character, there was a shift in the general atmosphere of the city that caused some new practices to rise to the surface, as the youth of the October insurgence expressed their long-repressed opinions through juxtaposing writing and painting. However, this creative convergence on the walls of the city, albeit spontaneous and not necessarily adhering to the desirable aesthetic conditions, had its own oxymoronic meaning, as the drawings were traced by bold young ladies, who, adorned in their black Abayas, joined their male colleagues, thus filling the works with a different kind of meaning and vitality within their surroundings. The seemingly simplistic graffiti scribbles on walls then become more than acceptable as a defiant exercise in a city which expects consistent coherence with its known guidelines.

Creative tents

Iraqi society has been shrouded in a cloud of frustration for the past 17 years, due to the successive torrent of bad news regarding the general decline on all fronts; the deterioration in educational levels, neglected urbanization, and the widespread slums. In this context, the emergence of cultural and artistic tents within the protest movement was an endeavor to form a successful ideal Iraqi entity that can redeem itself from the stressful, suffocating news. They manifested the people’s desire to achieve a wholesome model of excellence that is not only born out of the protest movement, but also grows in parallel to it on the ground. The creative tents were given various names, such as “Jawad Salim’s” tent (named after the pioneering Iraqi painter and sculptor), and there were several other tents named after the martyrs who fell in squares. In Baghdad’s Tahrir Square, the tents took on three different directions: 1- two tents specialized in cinema and theater; 2- some were street libraries with books available for reading and borrowing; 3- several other tents turned into forums that held debates and discussion seminars. The Bar Association’s tent, for example, belonged to the latter group par excellence.

In the other rebellious provinces, the sit-in tent was - for the most part - the incubator for any creative activity or discussion seminar, perhaps because the range of movement in Baghdad’s square was greater when compared to other squares that held cultural events of any kind, though without any specific focus, unlike in the capital, home to the “Cinema of the Revolution” and “Tahrir Theater” tents.

One truth remains to be proved regarding the reading tents: the people responsible for them put some books on display which stirred controversy. Some of those books were about intellectual subjects, some were novels or publications discussing Iraqi social history. However, a certain genre of books that were popular in “Al-Mutanabbi Street” after the fall of the former regime, were absent from the tent, such as the political memoirs that were previously banned in Iraq.

Iraqi society has been shrouded in a cloud of frustration for the past 17 years, due to the successive torrent of bad news regarding the general decline on all fronts; the deterioration in educational levels, neglected urbanization, and the widespread slums. In this context, the emergence of cultural and artistic tents within the protest movement was an endeavor to form a successful ideal Iraqi entity that can redeem itself from the suffocating torrent of bad news.

Everyone seemed to be in a rush to reach a level of citizenship that brought all groups to common grounds, where one could meet “the other” in the country, rather than follow or intersect with the other without having any real rooted conversation. Although, one must admit that this earnest meeting does not guarantee positive outcomes in terms of the depth of individuals’ awareness on all political levels later on, especially that their enthusiasm sometimes stems from a personal and collective weariness from the local disasters, and from the frustration caused by the many groups and components claiming to hold copyright of all truth and righteousness and prioritizing their own interests over the country’s well-being.

A photographed inventory

Besides the commendable characteristics of generosity and altruism that pervaded the squares during the demonstrations, the October uprising also gave us a good many photographers who eagerly shot and published photographs of the protest’s events and moods. The new images documented significantly contradictory situations that were happening simultaneously in the squares: death and life, bullets and roses, fear and hope, a people redefining itself, and authorities which persist in accusing this people of betrayal and hostility…

I recall the impact certain photographs had in shifting or upending the public mood on social media and changing the stances of many in the squares, while making visible aspects and realities previously unavailable to the public. It was no longer enough to hide behind the clichés that invoked conspiracy theories, while people came to understand that the real conspiracy lied in the consecutive loss of opportunity after opportunity to build and protect the country.

In Baghdad’s Tahrir Square, the tents took on three different directions: 1- two tents specialized in cinema and theater; 2- some were street libraries with books available for reading and borrowing; 3- several others turned into forums that held debates and seminars. In other rebellious provinces, the sit-in tent was - for the most part - the incubator for any creative activity or open seminar.

The photographs of the October revolt, with their faces, slogans, and banners, will remain as an inventory of a previous period in time. They will be preserved as documents which prove the cold-blooded murders and the many attempts to slander the movement or present it as a momentary and suspicious event. These images are, hence, evidence of the capacity of the promising individuals behind them to accomplish a lot for the country, had a better environment been available for them to create freely.

The photographic archive of those days will remain preserved. The rifle strikes that broke the lenses of some photographers’ cameras will bear witness to the events, as will the videos stored in their mobile phones, showing acts of terrorizing and intimidation against them, so that they would walk away from this path; the path of pursuing and documenting the sheer willpower of the Iraqi people in the squares.

Assassinated poems

Within the wide range of cultural and artistic contributions in the October uprising, dozens of poems were written, both in classical and colloquial languages, many of which showed solidarity with the youth’s revolution. One can infer that the popular uprising attracted poets into its midst, where poetry was not just a force that mobilized the crowd, but also one that fully supported the movement all along the way, and was indebted to the sacrifices of the young people who led the way.

Besides the commendable characteristics of generosity and altruism that pervaded the squares during the demonstrations, the October revolution also gave us a good many photographers who eagerly shot and published photographs of the protest’s events and moods. The new images documented significant contradictory situations in the squares of protest.

Part of the poems brought about some redemption for the murdered souls in the squares of protest; however, there were no particular breakthroughs noted on a stylistic or literary level, whether in the modern poems of prose or even in those written in Iraqi colloquial.

The poetry in those days recorded rather immediate situations or addressed specific names, while some prominent poetic voices were absent. Some of those absentees had their own sectarian convictions and interpretations which had been openly promoted since the movement began. Though their poetic texts were lacking, many other poets themselves joined the movement, organized, supported and interacted with the insurgence in varying degrees.

Children of a visual culture

What is the secret behind the emergence of the visual arts of graffiti and painting in the revolution in an eloquent and powerful way, unveiled and center-stage, bypassing all the poetic and theatrical activities that accompanied the revolution? Perhaps it has something to do with the relationship of the youngest Iraqi generation to visual discourses. It is a generation interlocked with modern technologies, and, though generally likes to read, it is nevertheless the child of a culture of the instant image. It finds in the shapes and lines it bestows on the walls an expression of itself and of the ideas it adopts. Without a doubt, it is an attempt that needs refinement, knowledge, and further experimentation. Indeed, there is an urgent need to learn from these art forms, as what had happened in October 2019 was but the beginning of a social change whose most potent features were those visuals and art works.

Saving victory for the days to come

Part of what made the graffiti paintings successful - whether those in the tunnel of Tahrir Square, Rashid Street, the streets surrounding Tahrir Beach, or those in the other different provinces - is the fact that they broke away from the populist temperament that characterized numerous activities and phenomena following April 2003, though still afflicted some of the 2019 pro-revolution poetic works, previously mentioned in this text.

The photographic archive of those days will remain preserved. The rifle strikes that broke the lenses of some photographers will bear witness to the events, as will the videos stored in their mobile phones, showing acts of terrorizing and intimidation against them, so that they would walk away from this path; the path of pursuing and documenting the sheer willpower of the Iraqi people in the squares.

The excellence achieved by these graffiti works can be understood as an act of transcending the present Iraqi moment, with its psychological and cultural dimensions, thus granting the youth an immediate victory that would leave a great impact on their future; an impact which can go far beyond the regions in which their graffiti paintings were made and shown.

The Iraqi “Museum of Innocence”

One is reminded, however, of the title of Orhan Pamuk's novel, The Museum of Innocence, which he later made into an actual museum in 2012, with 83 display windows that corresponded with chapters of his novel. We return to that bold, dreamy young man whom we had met by chance months ago, to repeat the same question: “Do you ever consider the fate of these art works? What if someone wiped them out, or what if the municipality workers removed them from all walls?”

The young man’s answer resembled everything the October generation stood for, in its rage, faith, and self-reliance: “Even if they do disappear for some reason, we’ll make a virtual museum that documents them all. We strive to organize a big exhibition one day that would show a complete collection of these works.” As emotional as they sound, these words are sincere, and it is because of them that we are able to rightfully declare: “At last, we have an Iraqi museum of innocence, made with the blood, tears, and dreams of those who seek sovereignty and independent national decision-making.”

• Photos of the graffiti by Houssam Al-Saray

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabah Jalloul

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 27/11/2020