Approximately two weeks after President Abdelaziz Bouteflika was transferred to a hospital in Paris due to a minor stroke, Algerians are tired of following news about the illness of the president. Concerns over Bouteflika’s health situation have significantly decreased, and Algerian newspapers — which are supposed to enlighten Algerians with explanations and information — have begun to neglect this matter.

Newspapers published crazy rumors and reactivated the idea that there is an obstacle to the implementation of Constitutional Article 88. This article stipulates that if the president of the republic — because of serious and long-lasting illness — happens to be unable to carry out his functions, the president of the Council of the Nation shall stand in as interim head of state for a maximum period of 45 days. After that time, the presidential seat shall be declared vacant, and the president of the Council of the Nation assumes the charge of head of the state for a maximum period of 60 days, during which presidential elections are organized.

Yet the [Algerian] public does not share in the media frenzy. Rather, Algerians have noticed that, as usual, things happen behind the scenes, and rumors and press articles are just a smoke screen to hide what is going on in secret.

Remarkably, the difference between Algerian public opinion and newspapers regarding this issue is reflected in the distance that separates each of them from the Algerian political system. In the public’s view, the so-called political system works spontaneously; Bouteflika’s absence or presence does not have any real impact.

This remark results from a sound belief that the political arena has been frozen in an authoritarian way for two decades, in conjunction with a strict authoritarianism imposed by pro-regime services. Bouteflika’s activity has significantly decreased since the first health problem he suffered in 2005, when he was transferred to the Val de Grace military hospital in Paris to undergo surgery, after he had been diagnosed with “a bleeding ulcer in the stomach.”

Thus, in light of the president’s few public appearances, minimum official meetings with officials or foreign envoys, and irregular ministerial meetings, Bouteflika’s third presidential mandate is stigmatized with political paralysis, while rampant social objection prevails. The abundant oil imports [Algeria received] in the 2000s have allowed the government to deal with this situation, even in a limited way, and to maintain the status quo.

The status quo

The political system in Algeria is still an authoritarian system, where the presidency provides the momentum for the government’s action and public policies. However, this momentum has been missing since at least 2005. This explains how Algeria has dangerously fallen, according to some analyses, into a routine where the ruling technical structure — which consists of the administration and security services — manages the country’s work, without having to be able to make the initiative. Thus the availability of financial resources allows the day-to-day management of the country to continue without any comprehensive strategy. Meanwhile the situation is rapidly developing in the entire neighboring region, with the exception of Morocco. The availability of financial resources allows the authorities’ groups to preserve the status quo, rather than benefitting from these resources to make the necessary changes.

“Algeria is missing a good chance to change the regime away from violence and foreign interference,” said a former Algerian minister, who added, “If the Algerian people are not showing an interest in the illness of President Bouteflika, it is due to the fact that they are convinced that the regime is not ready to bring about change.”

“At best, the president will be replaced, but what change does this bring? Behind the scenes, puppeteers will continue to control their puppets,” said an Algerian unionist.

This feeling that things cannot be changed is reinforced by the generalized weakening of partisan life, and the voluntary withdrawal of the most credible political figures, who do not want to participate in this masquerade. What’s more, the fact that the Algerian president is receiving treatment in French military hospitals also raises bitter criticism against the regime’s “bankruptcy,” which could not even establish healthy structures capable of taking care of its ruling political class.

Many find that this clearly indicates that the Algerian regime is bankrupt. This feeling of failure is reinforced by the fact that French officials have filled the void of the official Algerian media concerning the president's health situation. This media communication is practically monopolized by Said Bouteflika, the president's brother. This endless Parisian series further complicates things concerning the loss of credibility of the existing regime.

Joint stock company

The Algerian people doubt that the next presidential election, which is supposed to take place in the spring of 2014 according to constitutional deadlines, will be able to offer a chance for qualitative change.

For its part, the press is torn between the brunt of keeping up with the breaking news and resorting to the preferences of each and every bloc. It feels it is more involved than the others.

This press forms part of the regime, and it even plays the role of the alternative to a real political life. It is an arena for maneuvers and trial balloons. However, Bouteflika's disease remains an important issue in the life of the regime, as it puts an end to reports about a fourth presidential mandate for the current president, a violent battle that people close to Bouteflika were leading against other groups from the regime. From now on, no one will believe the scenario according to which the sick man may assume a fourth presidential mandate. This has become old news.

The muffled debate that is currently going on in the heart of the regime and that is expressed through press comments revolves around the question of whether Bouteflika is able to complete his current mandate — that is, until April/May 2014.

Succession?

The doors are now open for the succession of Bouteflika. This, however, does not necessarily mean that the next election — whether it takes place in 2014, or earlier if the president proves unable to continue to perform his functions — will be open.

Choosing the next president has become a secondary issue for the Algerian community, but a very important decision for a regime that the intelligence agencies and the military are tightening their grip on, along with increasingly dominant financial forces.

To summarize the status of the Algerian regime, we can say that the president, who enjoys at the official and formal level quasi-royal powers, serves as a cover for authoritarian, informal and non-institutionalized systems. The president enjoys great authority, but meanwhile, he is does not have total power.

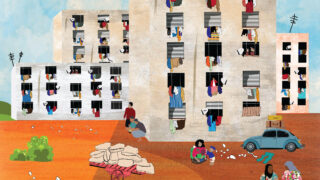

Algerians often make a play on words by using the common term SPA, which stands for "joint-stock company" (specifically, the initials of the Algerian power company). The president officially owns 100% of the stocks, but he actually shares them with other shareholders. This formal-informal system creates a mentality of irresponsibility, because presidential “deals” are not founded on a transparent contract between the president and the electors, but rather on business deals between himself and the so-called “real authority.”

When new elections draw near, the usual question is prompted: will the elections be closed or open? Until this day, all presidential elections have been closed. Those in the seat of power, not the electors, used to choose the president. This nomination system hit a dead end a long while ago, yet the civil war of the 1990s, which washed away the elites, caused it to remain. Additionally, the financial prosperity of the 2000s has placated social pressures.

Many Algerians perceive the illness of Bouteflika as less dangerous than that of the state. The country needs to negotiate a new social and political contract within an international context, especially amid the gloomy economic situation for Algeria, a country that is rich in gas more than oil. Algeria has reached the zenith of natural wealth, yet the potentials of enhancing its energy productivity (oil and gas) are still, at this point, weak.

The price of natural gas, which is an important pillar of Algerian natural resources revenue, is dropping. In this regard, long-term contracts, which stabilize financial revenue, are being reconsidered. The crisis and civil war of the 1990s came as a result of the deterioration of oil resources in the mid-1980s and the solutions proposed by the World Bank. Today, the components of the previous crisis are there, despite the large exchange reserve amounting to $2 trillion dollars. The upcoming crisis will be worse than that of the 1990s, even if it comes in a different form.

Of course, Algeria does not have a political “alternative,” since the political powers have been crushed under the grip of security agencies. Additionally, the political class has no credibility. The regime is capable of finding a successor to Bouteflika, and the potential candidates are many. Yet a new horizon will not emerge if the change of the president is not accompanied by more comprehensive change. One keen Algerian politician summarized his opinion about those in the seat of power: “None of them are wise men.”

Translated by Al-Monitor