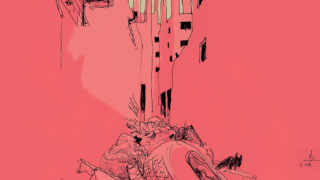

In their haunted capitol, Iraqis largely confront their demons on their own now; the American army is gone, and with it the interest of the world’s media and even most of the Arab press. But violent death is everywhere and increasing once again. Here, a lyrical account from Al Safir Al Arabi by Omar al-Jaffal.

Five days of every week, I must spend away from home. Five days in which the fear inside me grows and multiplies; fear that I will be murdered in a sectarian killing, that I will die in a car bombing, that I will be gunned down in some street carnival of machine gun bullets.

Five days, and then I go home to my mother. She receives me as if I were on homecoming leave from the battlefront. She sniffs my clothes, seeking the smell of gunpowder, examines the features of my face to reassure herself that my expression has not yet been visited by the madness of this capital where dread radiates through the streets.

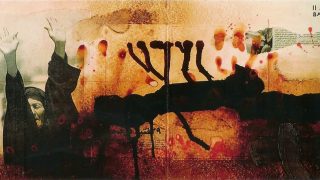

I have now completed 26 years of a life split between Baghdad and Damascus, two capitals that have sold their blood to the satellite channels, the newspapers and thinktanks. I have been here in Baghdad for the last two years. Here, I bury my face in my mother’s chest and sleep; maybe her scent will chase away the nightmares that hunt me in every daylight hour. When the weight of me is too much for her, I move away, take her hand and return to sleep. Sometimes I wake her up just to ask for a glass of water; not thirsty but wanting to know that we are both still here, alive in this city which drags us down the tracks toward its unknown destination.

Nights, I listen to her screams at the culmination of each consecutive nightmare, and these two nights a week, she listens to mine. We never ask each other about the devastated nightscapes of our sleep.

In the morning, she takes her tea with very little sugar, and I drink my coffee bitter. I kiss her on the forehead and take my leave, and her worrying begins. Each of us imagines the script of our death, writes a continuous succession of scripts for our murders.

Every morning I find myself touching things around me to be sure that I am alive. One day I found myself holding hoe to my head. It smelled rotten because I had spent the whole previous day walking in it through the streets of Baghdad with a friend. As we went along, we had kept repeating to each other, “Baghdad is a gigantic lunatic asylum.” I knew then that I was alive, and that the smell of life was as rotten as this shoe.

But why all of this fear? Between the 20th of March of 2003 and the 14th of March of last year, there were about 31,500 “death incidents” in Iraq, in which between 112,017 and 122,438 people were killed. Around a quarter of a million people were injured.

Baghdad has suffered the largest number of casualties. The capital lost some 58,252 of us (about 48 percent of all the country’s dead), according to the British NGO that catalogs the victims of the Iraq war. The clanking of the death machine in Baghdad is still very loud.

The bus driver is talking to himself. His words are perfectly clear. He curses this policeman, and all politicians. An old woman in a black abaya, tattoos on her cheek, answers him, tells him to calm down. But this only serves to make him complain louder. It seems that he was fined for not wearing a seatbelt.

Suddenly the old woman explodes in tears. The bureaucrats at the citizenship office are refusing to give her the one document that will prove that she is an Iraqi citizen, because she can’t find one of the “special documents” (to get anything done in any bureaucracy, you must always hand over four specific ‘Saddam-era’ documents at the same time). There is a drunk man, who seems like he has not stopped drinking for days, who does not care about what is happening around him. His gaze is lost on the streets outside the bus window, but he is looking at nothing, his body folded in around his lost center. A university student busies himself counting the day’s money, enough for the bus ride and a falafel sandwich. A skinny little boy pushes his head through the crook of his mother’s arm while her hands busy themselves with her prayer beads.

Iraq is a vast mental asylum, a mental hospital where there are no doctors. Each of us is afflicted with a different illness: dissociation, anxiety, paranoia, delusions. Some are capable of containing the outbreaks of their particular madness, until one day they explode. They explode in perfect loneliness; no one around them cares. We have lost all hope; we each gaze at our own condition, which does not improve.

You might be able to save up some money, but you cannot save yourself from the dread. I am sick, and so are every one of my friends, because of the insane death that awaits in ambush in every corner of this city.

I have not cut my hair in more than a year and a half. I think of the barber slicing through my neck with the sterilized razor, the hot blood gushing out, the other clients laughing hysterically. The blood is warm, my eyes are cold, and the razors are perfectly clean. I am no angel, no Rimbaud, to “live my life seated like an angel in the hands of a barber.”

The leaders of this country, past and present, have transformed us into creatures of paranoia, who suspect everything and everyone. Why have I become like this as well?

With every statistic I read, I sink deeper into despair, I walk closer to nothingness. I wheel hope into the morgue. The more that the uncounted wealth of the treasury is poured out, the thicker grow the tides of the poor who crowd the streets. This city is an alien to its own people. Those who were born ten years ago can have no reason for affection toward this place; how can they love a city that has given them nothing but murder and failure and disintegration? Baghdad is it you who has mutated? Or is it your people? Or perhaps it is those who lead us?

Translated from Arabic by International Boulevard