As it is already well known and established, shared life of Jews and Arabs did exist in Historic Palestine prior to the Zionist settlement and to some extent maintained through the first decades of the 20th century. For us, this raises both a theoretical and a political question. That is, we ask what can be learned from this acknowledgment. What can the knowledge about this reality of the past teach us about our present and how can it serve us towards the future? How can we understand this reality not just as a testimony of the complexities of the past but rather as one which possesses an actual political value today? For us, the answer lies in the understanding of the ways this reality ceased to exist, the modes of its transformation and disappearance, and how this was part of the formation and consolidation of a new order, a settler colonial order, which replaced the reality of shared life and of which we are still part.

The law of motion of settler-colonial projects is to uproot the native in the process. That is, the social frames and ecologies of life that sustained and spatialised native existence are vandalised by the settler in the creation of its new society. Eliminating the native means dispossessing space from its native routines, ecologies, sociabilities, institutions, and assets – whereby life itself is dispossessed from its native forms. Two interconnected processes create a new structure: the settler polity emerges only on the condition of dispossessing life from its native forms. The challenge to native forms of life in Palestine began as early as late nineteenth century with the arrival of the first wave of Zionist immigrant-settlers, and intensified and consolidated in the years to come. Their dealings with land, their separatist practices, and their cultural mannerisms awakened more than just concern amongst Arabs and Jews already living in Palestine. It did not take long until colonization in Palestine shaped a tendency and a form that not only opposed but sought to destroy the conditions of existence of the traditional forms of life in the country. In this light, our first question is what were the forms of native life that existed in Ottoman Palestine and which Zionism sought to eliminate in its formative stages?

Before Zionist immigration began making a historical impact by the third decade of the twentieth century, the Arab majority in Palestine and the Jewish minority – most of them Oriental/Mizrahi Jews – were socially espoused by way of a myriad of cultural, political, and economic everyday practices. Shared life was a form of normality that structured the everyday of the natives of Palestine, Arabs and Jews. Yet, for these practices of shared life the encounter with the divisive strategies of Zionism was fatal. A rupture has taken place. In the transition to the consolidation of Zionist community in Palestine, forms of life and modes of being have changed or disappeared. In studying the elimination of native life in modern Palestine the loss of Arab-Jewish shared life cannot be ignored. We use ‘shared life’ not to stress the mere cohabitation of different racial subjects in the same space, but we refer to the historical implications of Arab-Jewish familiarity as it evolved during hundreds of years in the Arab world, and also in modern Palestine. As Elias Sanbar stressed, the source of legitimacy of the shared indigeneity – its Arabness – is that which brought the Jewish settlers to reject these spaces as liveable. European Zionists conceived the native content as racially, culturally, and physically incompatible with Zionism. They did not see the reality of shared life in Palestine as one they desired to become part of. And thus, the content of this shared indigeneity was made a target of elimination by the emerging settler colonial mechanisms of Zionism in Palestine.

Native elimination in Palestine involved the destruction of Arab society – the annihilation of its cultural hegemony, the dispossession of land, and the removal of its demographic supremacy – but also the racial rejection of Arab-Jewish sociabilities, of shared life. Both series of operations intertwined as part of the organisation of the emergent settler-colonial society. These operations shaped the organs of the Zionist body. Thus, elimination in Palestine developed as double elimination. The dispossession and displacement of the Arabs of Palestine became a necessary but insufficient condition in the Zionist settler-colonial project. The process of dispossession and displacement of the Arabs was complemented with the destruction of the social and cultural infrastructure that made Arab-Jewish life an identity and a historical reality. Native life in Palestine had, from the point of view of the settlers, two aspects, constituting two targets: Arab-Jewish shared life had to go as much as the Arabs of Palestine had to go.

This conceptualization and analytical framework help us not only to better understand the evolvement of the settler-colonial formation in Palestine at the expense of the Palestinian people, but also to delineate the origins of racist tendencies and practices of Zionism towards Oriental Jews, before and after the establishment of the state of Israel. Another aspect of this process was to be witnessed in the transformation of shared life from a full life-form that it was in the past, into a political idea, an ideology and discourse, which became coded as ‘Arab-Jewish cooperation’. Once a life, under settler colonial machines the fruitful composite ‘Arab-Jewish’ quickly became spoken rather than practiced. With the displacement of native life, the discursive form of the Arab-Jewish displaced its prior material actuality.

The structure of elimination holds constructive insights to think not only the past but also to think the present politically. We don’t strive, nor is it wanted or possible, to recuperate what was gone. Politicising the understanding of how the formation of Zionist life in Palestine was and remained dependent on double elimination means something else. It is to ask our second question, what does the structure of elimination say about the possibilities of decolonisation?

Zionism has made shared life, at most, only a virtual competitor. Yet, this is the result not only of a segregationist past, but the day-to-day production of existing social machines. Social life in Jewish-Israeli society is structured to inhibit altogether the possibility of Palestinians and Jews to come together in a civil way. That is, the destruction and prevention of shared spaces explain our past as much as our present. If Palestinians and Jews had to be separated as one of the existential conditions for the emergence and persistence of the Zionist settler-colonial formation, thus it only makes sense to argue that at least one way to bring that regime to malfunction is to insist on desegregation by articulating the Arab-Jewish composite within the struggle for decolonisation. If shared life was and remained a target of the Zionist settler-colonial project, then one should be able to contemplate the power of this social composition to resist the project. Given that shared life is not a possibility, under colonial conditions, coming together can only mean recruiting the Arab-Jewish composite as part of the struggle for decolonisation, that is, in the form of a Palestinian-led co-resistance.

A minimal knowledge of the Jewish-Israeli society forces us to realise that the possibility of co-resistance is limited, and constrained by colonial modes of being. Therefore, to articulate the possibility of co-resistance, one must ask a third question, what are the cultural conditions preventing Palestinians and Jews from coming together?

During the last hundred years, the relations that have chained Israelis and Palestinians have moulded Israelis as dispossessors. How does this materialise in Israeli society today? To work this out we need to compile and expose a detailed archive of everyday activities that show just how extensive and ramified is the network of practices making Israelis into colonists. Looking into family life to begin with, good parents are those who sacrifice, in body and soul, their offspring, by seducing them into the military, and also by normalising their own military experience as a triviality. In school life good teachers are those who consolidate the formation of racial distinctions in our way of seeing the world. Soldiership itself is paramount in the training of Israelis as colonists. Yet, becoming a colonist takes place in the most ordinary moments of life such as in hiking narrativised outdoors, in the everyday conversations we maintain with our friends and families, but also in obeying the law, and in taking part in the procedures that elect those who rule millions of colonised Palestinians – all these social practices aggregating and galvanising into one of the strongest, coherent, and ready-to-do collective mode of being of modern times.

In Israeli society, one is ordained to become a willing oppressor.

Though there is no unified Jewish subject condensed by a homogeneous set of histories and interests coiled around Zionist ideologies, most Jewish-Israelis – despite their differences – enact in their everyday Zionist practices, and have as their common denominator the hatred of Palestinian presence: fanatic religious nationalists and hypocritical secularists, Mizrahi and Ashkenazi, Ethiopian and Russian, women and men – all glued together by a collective fantasy: to wake up one morning to an Arab-free society and land. Can the social formation of the colonist be transformed? This is not an easy task. Being a colonist immersed in a day-to-day gallery of oppressive practices as a condition of life, brutalises. How otherwise can we comprehend the combination of those soldiers who shoot unarmed Palestinians demonstrators, and those people in kibbutz Nahal Oz and Sderot making the massacre of Gazans into a show watched from makeshift balconies?

We are pointing to a historical constraint that must be accounted for: to abolish the colonial relations that Israelis are part of means also to abolish the collective character of Israelis; it means to do away with their existing social formation. Their present colonial constitution is unsuited for a society of equals. This is the catastrophe that defines not only the Palestinian predicament, but necessarily, also the character of Israeli existence and form of being. Surely, as Albert Memmi claimed, “it is not easy to escape mentally from a concrete situation, to refuse its ideology while continuing to live with its actual relationships”. Freeing oneself from the pleasures of Zionist oppression is a long process through which one abandons the roles, functions, the social relationships, and the privileges and benefits that makes Israelis into what they are.

We believe that the conditions that need to be considered as minimal in order for Zionist colonists to become able to step outside their mode of being are: (a) acknowledge the causative relation that weds the fate of the colonised to your privilege; (b) renounce on Zionism; and (c) follow the lead of the colonised. The goal is to induce a generational change of hearts and minds. This is certainly a huge challenge, but one that makes clear that there is no room for “peace processes” within Zionism.

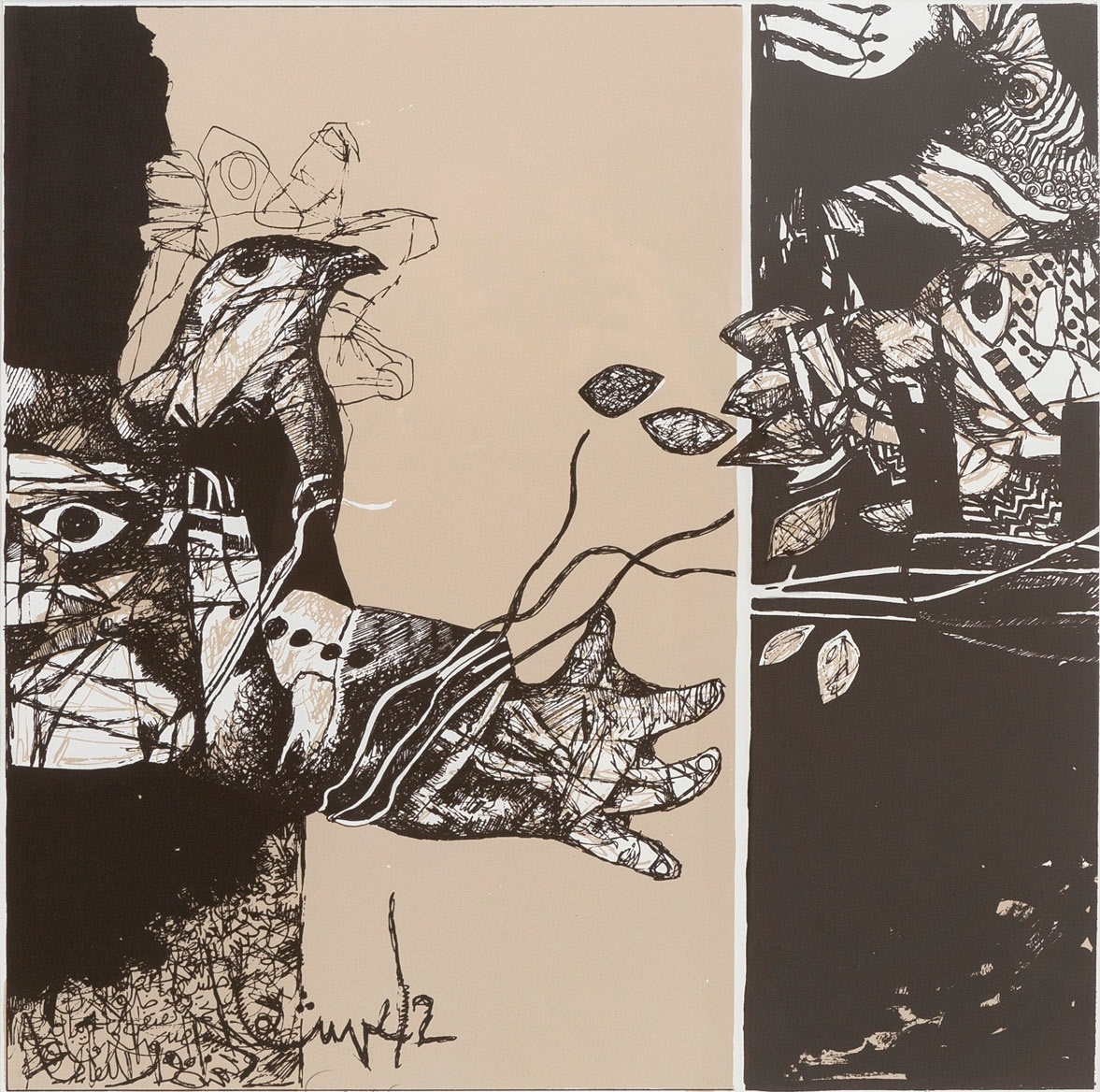

How to conceptualise the activist work of those who refuse Zionism? In the meantime, this activist work need to be seen as a work of cultural preparation. At present, this is an important contribution to the process of decolonising Palestine. However small and fragile, this activist work creates some of the tools which eventually would serve to reconstruct life between the Sea and the River. The contribution of this activist work, its critique, is to pierce and tear the boundaries of thought and action that Zionism has fixed. The impacts of this activism are less dramatic than we tend to think, and its vocal champions are less influential than we want to believe. But one day, in retrospect, the artefacts of this activist work will play a role in the constitution of the collective consciousness of a people yet to come.

Conference at Brown University, April 2018.