This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Following the US occupation of Baghdad in 2003, serious problems materialized, one of which was that government offices were being taken over by families who did not had no place to live. They came from various regions, but mostly from the southern governorates. In a matter of days, things got out of hand as public land was being seized in the central cities, such as Baghdad and Basra. Thus began the journey of establishing the present informal settlements.

Not the first time

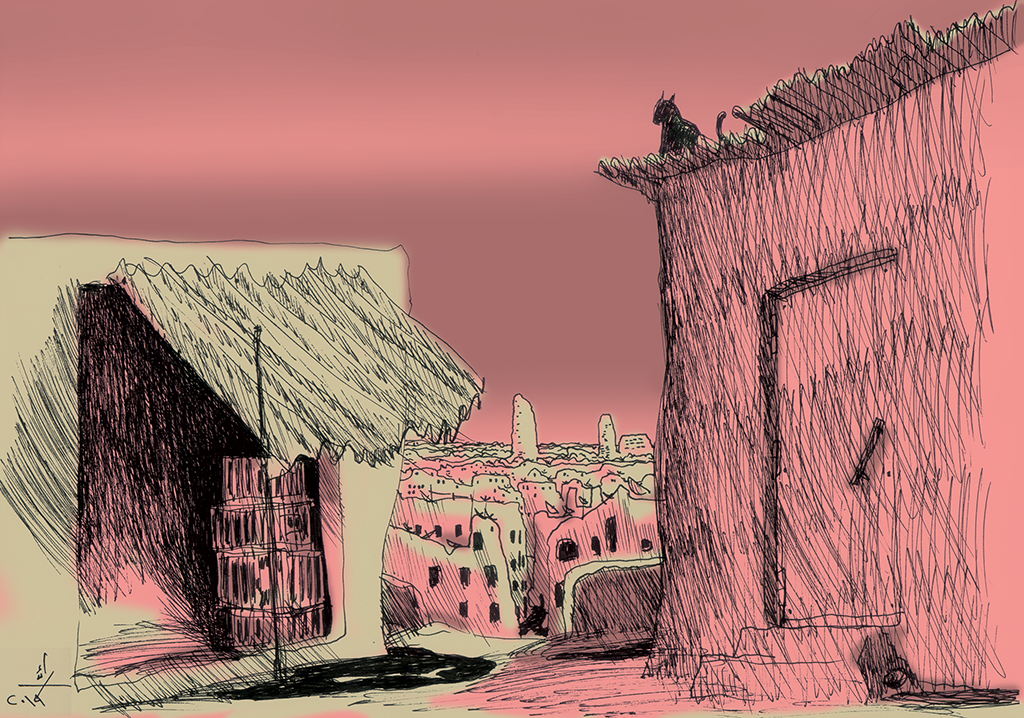

Baghdad, in particular, has previously witnessed the birth of informal settlements, the most important of which are those built with mud on the fringes of the capital from the northeastern side. Called Khalf al-Saddah areas, these slums witnessed an exodus of farmers from the southern governorates, especially Al-Amarah. After the 14 July 1958 revolution and the declaration of the republic, these areas turned into a new city called Al-Thawrah. Constructed in 1959, this city of modest houses of similar design was to house the residents of Khalf al-Saddah. However, late President Saddam Hussein wished to name it after himself, though he was unsuccessful in doing so. Finally, the city was named Al-Sadr after Sayyid Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr (who was executed in 1980) and Sayyid Muhammad Muhammad Sadiq al-Sadr (the father of Muqtada al-Sadr, who was assassinated in 1999). It remains today known as the city of Al-Thawrah/Al-Sadr.

Post-2003 slums are not the same as the earlier ones; they are larger, extended, and more scattered. New and big slums expanded over the land of the first informal settlements, such as Khalf al-Saddah, with every slum complex springing adjacent to the other. The only difference between these slums is the degree of their “informality” and “randomness”.

There are areas built on agricultural lands whose plots have been sold to people by their owners or by influential party and militia entities. Moreover, others were totally illegal; they were built on either state-owned or squatter lands.

Khalf al-Saddah again

Behind the eastern borders of the city of Al-Thawrah/Al-Sadr, the Khalf al-Saddah areas are lined up. They are areas built on land that has been, for a long time, either cultivated or became a landfill. The visitor can notice effortlessly that the air is foul-smelling with the odor of waste and sewage water. The irregularity of the sub-streets, where some start with a width of three meters and end with one meter, is clear due to the lack of planning. Almost all informal settlements lack services and infrastructure, even those where electricity and water lines have been laid. Because the urban planning of cities did not take these areas into account, the facilities added are deducted from the official quota of the cities, which inevitably affects the latter's supply.

Not all slums are built on spaces outside the urban cluster of cities. Many have sprung up in the middle of cities, taking advantage of small green squares or spaces left empty as a breathing space for the legally built neighborhoods. At the intersection of Al-Karradah, one of the central areas in the capital, Baghdad, and Al-Zaafaraniyah alone, there are 43 informal settlements comprising about 24,500 housing units, according to an official source in the Al-Karradah Municipality Department.

All informal settlements represent a double burden on the resources and the infrastructures that have not undergone proper development or maintenance. The government also has not provided a well-studied solution to the issue of increasing slums. In fact, it left it to exacerbate, along with the problem of the rapid population growth, with about 1 million being born every year.

Almost all informal settlements lack services and infrastructure, even those where electricity and water lines have been laid. Because the urban planning of cities did not take these areas into account, the facilities added are deducted from the official quota of the cities, which inevitably affects the latter's supply.

Moreover, there are slums built on prohibited zones, such as the lands beneath which are large quantities of oil reserves. These areas are identified by the crosses placed over them, indicating that they are oil fields belonging to the state, such as the slum of Alwat Zwayni near Sahat 83, which is adjacent to the city of Al-Thawrah/Al-Sadr. Anyone who visits these areas for whatever reasons is certain to find many realities of which the state knows nothing.

The raw image

A barefoot child runs fast across an unpaved street that looks like an alleyway of dirt and rubbish. As his friends try to catch up with him, the T-shirt on his back seems hardly discernible. It is a commercial copy of the sports T-shirt of the Spanish soccer club, Real Madrid, known for its white color and the navy stripes on its edges. At least those were its colors before they faded on the child’s shirt due to time, dust, and dirt.

All but one of the five children have dropped out of their schools. The oldest is no more than eleven years old, which means that they are a little bit younger than their small, recent area of residence, which is built of old bricks, zinc-iron sheets, and a lot of trash. This area is under one of the main power transmission lines in Hayy al-Risalah, southwest of the capital Baghdad.

Maps of Deprivation and Dissolution in Iraq

20-08-2015

The number of houses in this neighborhood does not exceed 30. Per Ministry of Planning figures, there are about 3,700 informal settlements across Iraq's various governorates, inhabited by an estimated 3 million people. Baghdad has the largest share of about 1,000 informal settlements, followed by Basra with 700 ones. All informal settlements represent a double burden on the resources and the infrastructures that have not undergone proper development or maintenance. The government also has not provided a well-studied solution to the issue of increasing slums. In fact, it left it to exacerbate, along with the problem of the rapid population growth, with about 1 million being born every year.

One of the few reckless attempts to deal with the problem of slums was the campaign launched by local governments, municipalities, and the Capital Municipality to remove building encroachments. They demolished a number of homes without providing housing alternatives.

The residents of these slums are not similar in their professions or social characteristics. However, the deterioration of their economic conditions and the difficulty of owning or renting houses in cities due to high costs often pushed them to live in these areas. Most residents are self-employed. Their work is often arduous, such as construction jobs, which do not generate sufficient returns for workers, not to mention that they are not stable. However, they all share living in areas with dirt streets that lack the most necessities of human life, where adequate services have never been present. These circumstances contribute to the multiplication of problems in these areas and the distortions that affect their social structure.

Distorted features

On the southwestern side of Al-Karkh in Baghdad and behind the Hayy al-Turath area, whose streets have not been fully paved, a slum has expanded, along with its big troubles, complexities, and problems. Its residents, most of whom are cousins and brothers, are from one clan that controls this area. That is why the area adjacent to Hayy al-Turath is named after this clan.

Ali Muhammad Sabry, a former resident of Hayy al-Turath, describes the experience of living with his family there as terrifying. He said that an affray had lasted for a week amid an exchange of fire due to an internal dispute among the clan members who reside in the "encroachment area," the common term in Iraq to describe informal settlements. He recalled how he was unable to leave the house at the time and go to take some of his university exams. He said: "We got rid of this problem with difficulty because our house in Hayy al-Turath was low in price, and no one wanted to buy it."

It is not an isolated incident. Due to the failure of state agencies to perform their functions, the behavior of alternative forces to the rule of law has become rampant. The closest alternative is, of course, the clan. This fact becomes concrete when you live in an encroachment area that witnesses, from time to time, battles with light and medium weapons due to a clan dispute that might disrupt public life in the battlefield area. These battles always deprive the area's daytalers (a majority) of their daily livelihood and inhibits the children of attending their already scarce schools.

Uncertain future

Not only do informal settlements suffer from the lack of the rule of law, potable water, and electricity, they also complain about the scarcity of schools. Most children are forced to walk long distances to reach the nearest school in the neighboring residential areas. Children who do not attend schools at all also have to walk to work.

The government was forced to reapply the temporary “subscription for a fee”. It requires the Ministry of Municipalities and the Capital Municipality to provide clean water. It also obliges the Ministry of Electricity to supply electric power until the Iraq Council of Representatives issues the law regarding building violations, which has been stuck in parliament since 2017.

The Iraqi slums also lack adequate health services. They suffer from a lack of health supervision and care, except for a few areas where the government has opened health clinics, albeit with poor capabilities, in the places where the relevant authorities were forced to acknowledge the land ownership of their residents despite their chaotic planning.

The Slums of Khartoum: On Life’s Edge

21-05-2022

Invisible Slums: “Al-Ghaba” in Tunisia’s Sfax

01-06-2022

Without appropriate planning and with the lack of a serious effort in seeking solutions to the slum crisis and alleviating human misery, the future seems uncertain despite the few reckless attempts. The most recent endeavor was the campaign launched by local governments, municipalities, and the Capital Municipality to remove abuses and encroachments and demolish some homes without providing housing alternatives. The campaign had sparked public anger, with some people describing it as arbitrary.

Thus, the government was forced to reapply a temporary “subscription for a fee”, whereby it requires the Ministry of Municipalities and the Capital Municipality to provide clean water. It also obliges the Ministry of Electricity to supply electric power until the Iraq Council of Representatives issues the law regarding building violations, which has been stuck in parliament since 2017.

However, all Iraqi cities are faced with the reality of tolerating inadequate services. It represents a kind of deficiency complex from which people who live in informal settlements have always suffered.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabry Zaki

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 12/12/2019