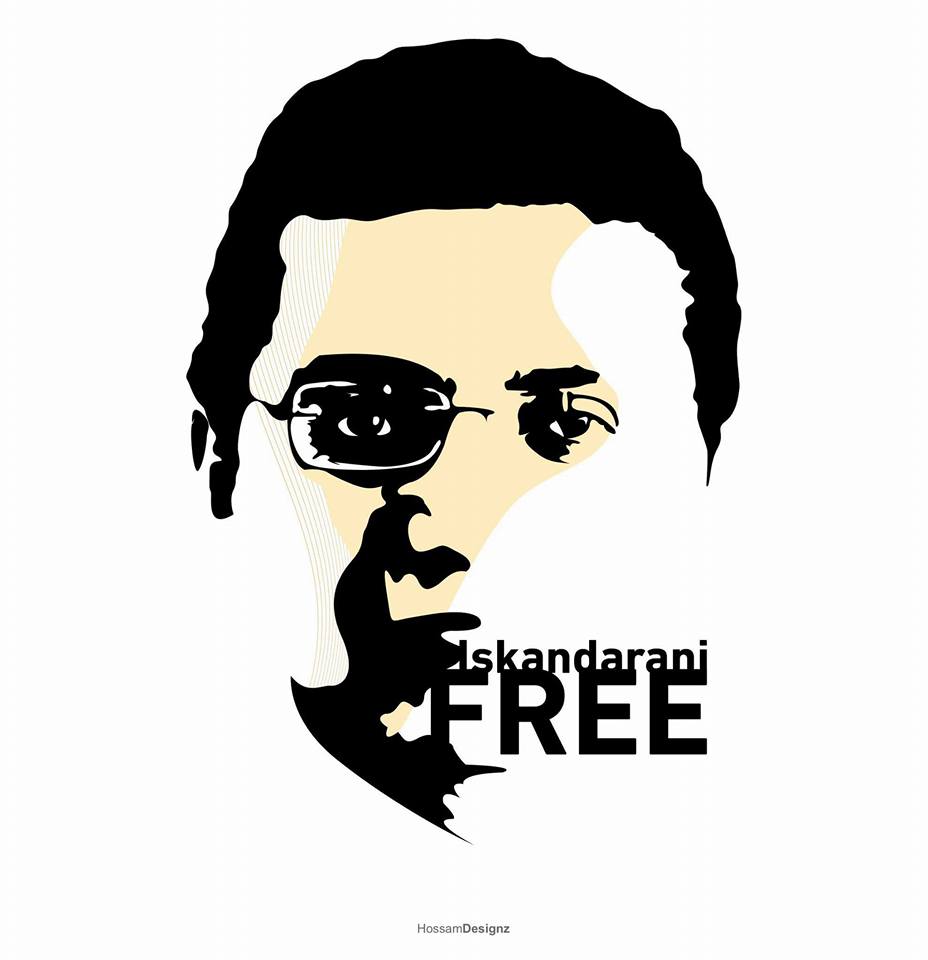

There are not many Egyptian journalists like Ismail Alexandrani. A sociologist by training, he was always drawn as a writer and journalist to those who are marginalized in the excitable hurly burly of Egypt’s press and popular culture: Nubians, disabled people, the Sinai Bedouins. It was his interest in the people of the Sinai, separated by a narrow canal but a wide cultural gulf from the people of the Nile Valley, which eventually turned him into perhaps the world’s leading expert on the insurrectionary armed groups there. And this week, his expertise and erudition have dealt him a grim fate: he has been arrested and is being held incognito on improbable charges of supporting terrorism.

Forced to live abroad since last year, Alexandrani tried to slip into Egypt under the radar this week to visit his ailing mother. But the Egyptian embassy in Germany tipped authorities off that he was flying into an outlying resort city on the Red Sea coast, and he was duly snatched up at the airport and bundled off to the forbidding headquarters of State Security Investigations in Cairo.

Alexandrani has always been willing to work against the grain. In the early days of Egypt’s ultimately failed Arab Spring ‘revolution,’ he wrote an insightful essay criticizing the cult of martyrdom which had then been built up around Khaled Said, the young man whose beating death at the hands of Alexandria policemen inspired many of the young activists in 2011 to demonstrate against the regime. We are not all Khaled Said, Alexandrani wrote: we do not all have good teeth, expensive clothes, live in nice neighborhoods next to the sea, and have a foreign passport that lets us travel wherever we like. Though common, lower class Egyptians beaten to death by policemen do not make for good Facebook campaigns, they are equally if not more deserving of our solidarity, Alexandrani suggested. The essay was, perhaps needless to say, never published by any media, local or foreign.

Even before the military coup which stripped power from the elected Muslim Brothers in the summer of 2013, Alexandrani was warning that the militarization of the Suez and Sinai regions of Egypt’s east was a mistake that could cost Mohamed Morsi his presidency, opening a way for the military back into Egypt’s public life; this “could be the beginning of the end of the Brotherhood rule in people’s hearts,” he wrote. Morsi was overthrown six months later, with the military promising to restore stability as it had supposedly been doing in the Sinai.

The reality in the Sinai was far from stable. After the coup, Alexandrani’s attention turned to the armed groups which had arisen among the northern Sinai’s largely Bedouin population; Jund al-Islam, Ansar Beit al-Maqdis, shadowy groups of angry young men who blew up the pipelines selling Egyptian gas to the despised neighbor and former occupier, Israel, or who murdered policemen and fired the odd rocket. The Egyptian state’s scorched-earth responses, with mass imprisonments, demolished houses, hostage-taking and occasionally the dynamiting of whole villages, was, he wrote, not going to bear anything but poisoned fruit.

That poison has come in the resurrection of the extreme-even among extremists-ideology of takfir: treating everyone in the broader Muslim society as a heretic deserving of execution, Alexandrani wrote in an article translated here recently. The extremists of the Sinai swore allegiance, first to Al-Qaeda, and then to the Iraqi-Syrian entity that calls itself the Islamic State. And their attacks on policemen mutated into enormous car bombs and blown-up airliners. Egypt’s generals got what they may have wanted all along after the coup and the horrific massacre at Rabaa al-Adawiyya and the mass arrests and mass death sentences pronounced against innocuous political actvists: a full-scale, though hopefully manageable Islamist insurrection.

And now they have Ismail Alexandrani as well, a fine and honest journalist who has always pointed out the Egyptian military-state’s errors and miscalculations and horrific mistakes, and who will now pay very dearly for working against the grain in a country which no longer tolerates real criticism of its violent and brutal military regime.

Jack Brown

International Boulevard