This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Although climate change and its effects have become a fait accompli, nobody in Syria seems to be addressing the issue of climate change with the seriousness it demands. This applies to the various authorities in the country who see the issue as a superfluous burden amid other agonizing circumstances, and in doing so, they fail to recognize how climate change links to other social, economic, and humanitarian problems.

In 2021, CO2 emissions in Syria increased by 1.01 megatons, 4.06% more than that of 2020. Syria currently ranks 108 out of 184 countries on the list of countries classified from least to most pollutant by carbon emissions.

New, harsh climate cycles in the east of the Mediterranean have become more frequent, causing delays in rainfall and inducing acute dust waves. In addition, the substantial pollution created by the toxins of various kinds of shells, as a result of years of the Syrian conflict, is visible in the rising cancer rates in the country.

Climate Change: It’s About Time!

29-12-2022

The Struggle for Climate Justice in the Arab Region

21-01-2023

Damascus and the other de facto authorities have not yet declared what they would do if the waters of the Euphrates River continue to decline due to the dams and Turkish policies. They also did not reveal their plans for reducing the pollution of Syrian rivers by wastewater, nor did they declare how they would address the unusability of large, formerly arable areas, the dwindling production of wheat, cotton, and vegetables, and increased desertification due to climate change and failed policies, as well as how to provide drinking water to more than half of the Syrian population with no access to clean water resources.

Government policies

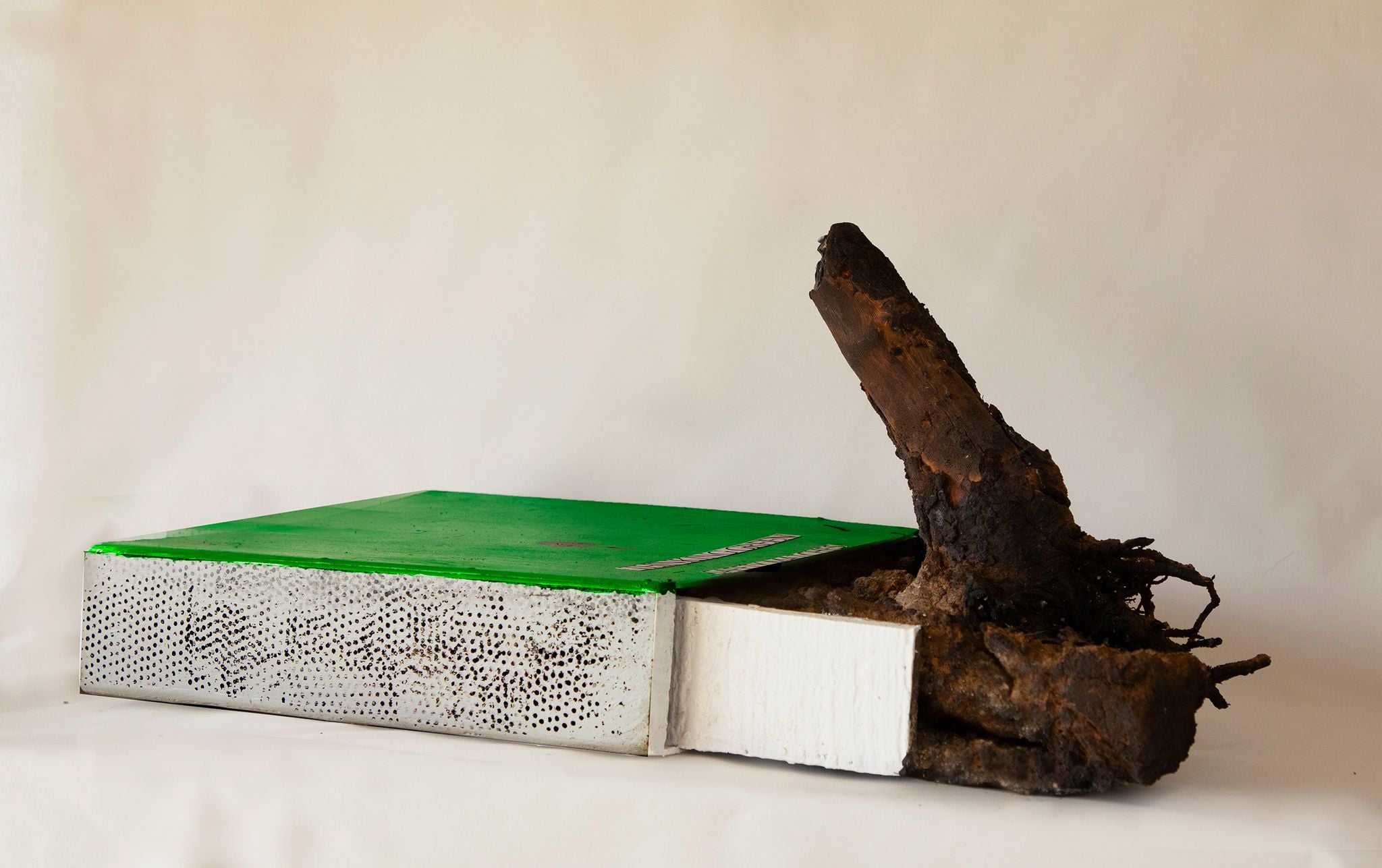

Long before the protest movement of 2011, the Syrian Government has ignored the people’s needs on the pretext of “external” reasons and pressures. Most areas, especially slums, were taken back to the pre-water, pre-electricity times. And although many cities and villages were not destroyed in the war, they still ended up paying a price similar to that paid by the villages which had been leveled, as they, too, were deprived of energy and fuel. In 2022, and right before the winter, the government reduced the citizen’s share of fuel oil from 200 liters to 50 liters without officially declaring it. In 2021, many regions including Al-Suwayda, Rif Dimashq, and Qadmus were completely deprived of the 50-liter share. This forced many Syrians to revive old ways and habits in cooking, washing, and heating. They logged the remaining trees in gardens and streets, while the many mafias of the country took it upon themselves to destroy whatever was left of the forests and sidewalk trees, selling their wood for heating. At the beginning of the winter of 2022, the price of one ton of firewood reached 900,000 Syrian Liras (about $200).

The clearest example of how the Syrian government manages the contingent environmental crises was how it dealt with the leak of no less than 15 thousand barrels of fuel from one of the tanks of the coastal Baniyas power plant in June 2022, polluting the coast and the sea to a depth of hundreds of meters. The Syrian government officially denied the spill, considering the news and images circulating as “baseless Facebook chatter”. Nevertheless, when things got worse and the spill extended to the coastal cities of Jableh and Latakia and even reached Cyprus, the government conceded, yet used traditional ways to clean the coastal strip, leaving behind thousands of gallons of fuel that would kill the last of the already-scarce marine life.

These policies of denial do not negate the work of certain domestic agencies such as the Ministry of Environment, the Directorate General of Meteorology and the Authority for Remote Sensing to study and follow up on the climate change problems, by virtue of their bilateral agreements.

These agencies network with relevant international organizations. Damascus has ratified the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change of 1995, signed the Kyoto Protocol of 2005 and the Paris Agreement of 2015, and submitted several reports to international agencies. However, it has categorically denied its responsibility and dereliction in these reports.

Syria: Any Last Survivors?

29-12-2022

In November 2018, the Government submitted a report entitled: Document of Syria’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) (1) under the Paris Climate Agreement, where it pinned the delay in responding to climate challenges on what it called “the terrorist war” which “has impacted on the climate and on the national efforts and resources available to face the various aspects of the repercussions of climate change.”

Long before the protest movement of 2011, the Syrian Government has ignored the people’s needs on the pretext of “external” reasons. Most areas, especially slums, were taken back to pre-water and pre-electricity times. And although many cities and villages were not destroyed in the war, they ended up paying a price similar to that paid by the towns that had been leveled.

The report points to several practices by different parties that had an impact on the environment in Syria, including the operations of the so-called International Alliance. It also refers to local phenomena that the international policies have nothing to do with, such as forest logging and desertification, but the report repeatedly blames them on “international policies and sanctions” that prevented the Syrian State from maintaining the course of sustainability, arguing that “the main reason is the policies of the developed counties", in clear disregard of the government’s role in failing to address these challenges in the years before and after the war.

The report also denies Syria’s contribution to climate change, restricting it to one aspect of this multifaceted phenomenon, which is greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, indicating that the total amount of Syria’s emissions is 79.09 megatons of CO2. This figure is significantly higher than the international standard which allows a maximum of 25 megatons. The energy sector contributes more than 73% of these emissions due to the use of fuel and gas in the production of electricity, without an integrated national strategy to move to alternative energy. The government’s plan is that by 2030, “alternative energy would contribute 10% of energy production, provided that real support from international donors is provided to execute the alternative energy projects,” according to the NDC.

Absence of governmental climate justice

The Syrian State’s engagement with the international community regarding the problem of climate change is not limited to blaming external parties and begging for aid and funding, in the absence of much-needed national plans that address the issue. It also includes an unjust approach in dealing with the results and consequences of climate change in the country by giving priority to certain regions at the expense of others. In both cases, confronting climate change is based on the logic of addressing emergencies, rather than mitigation and sustainability.

For example, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad promised in a statement that the government would offer the greatest support to the victims of the 2020-2021 wildfires (about 140 thousand people). In reality, the government granted scanty financial and in-kind compensations that do not match the number of victims or the size of the damage. All support was superficial and had no real effect; it was a haste response which lacked an effort to rehabilitate or develop the stricken villages and towns. On another level, the fires of the coastal forests have unveiled the decline of the Syrian Government’s capacity to provide the civil defense with the equipment and manpower necessary to fight wildfires.

The governor of Latakia announced on the 15th of October 2021 a government aid grant of 1.53 billion Syrian Liras ($660 thousand according to the official exchange rate at the time) to the villages damaged by the fires in Latakia; the share of each being 10 million Syrian Liras ($4300). In addition, 500 million Syrian Liras ($125 thousand) were allocated as non-interest loans to the farmers to compensate for their loss of trees, livestock, and lands.

According to these figures, the individual's share of these compensations in a village populated by a 100 people would not exceed 100 thousand Liras or $20; a sum that is not enough to make up for the loss of a single olive tree. Moreover, a large part of these compensations was spent on the yield of a single season of fruitful trees, and their distribution was marked by corruption.

In Al-Hasaka, as in the Syrian South, the wildfires of 2021 devoured the wheat seasons. The government did not heed the farmers’ calls for help despite hundreds of appeals that were submitted to the governor and the General Union of Peasants. In addition, the sheep breeders were left alone in the face of the drought that hit the Syrian Desert during the same period.

The policies of other Syrian parties

The Syrian Government was not the only authority that neglected taking necessary measures that should have been applied before, or even during the war. The authorities in Northern and Eastern Syria, as well as the so-called Syrian Interim Government (SIG) in north-western Aleppo all excluded climate change from their agendas. Sustainable environmental methods were overlooked, as were the relevant tasks such as water sustainability, recycling solid wastes, and afforestation. Most worryingly, no efforts were made to stop the primitive oil extraction operations in the regions of Raqqa and Deir el-Zor, or to stop logging activities in Rif Idlib.

In the Jazira Region, drought and desertification are far from being considered a priority to the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, at a time when other, more serious crises, such as the scarcity of drinking water, are escalating.

In October 2021, a report issued by the United Nations Security Council (2) stated that “Millions of people across the Jazira Ragion are affected by the water crisis and are unable to reliably access sufficient and safe water on a regular basis, as a result of environmental circumstances imposed by the conditions of the ongoing conflict .”(3) According to the UN's Action Plan, which was announced on September 9, 2021, the access of 5.5 million Syrians to basic water supply is in jeopardy, after the Euphrates River water levels have dwindled since January 2021. The decline in the flows from the upstream Turkey, accompanied by irregular and decreasing rainfall and higher-than-average temperatures, have all contributed to creating drought-like conditions in the Jazira Region.

The critical situation in the Syrian Jazira is largely attributed to the effects of climate change, in addition to the Turkish policies against the population and weaponizing water against the Autonomous Administration. This, however, does not absolve the local authorities of their responsibilities, as they have repeatedly ignored the changes in the region during the years in which various resources were depleting. Soil salinization and the desertification of vast areas of land went untreated, and the authorities adopted policies of neglect and indifference instead.

In addition to the climate factors that accelerated the water crisis, civilians’ access to water diminished due to the decrease in the operational capacity of the water supply system. The European Cascades Project (4), published in January 2022, studied the effects of migration to Europe; it noted that that the percentage of Syrians who can access sources of safe drinking water in the Jazira Region does not exceed 50%. The closure of the Alouk Water Station (in Al-Hasaka) prevented about half a million people in the region from accessing clean water. Al-Khafsa Water Treatment Plant that supplies Aleppo with the waters of the Euphrates River, as well as Ein al-Baida water pump that supplies water to about 200 thousand people in Raqqa, have encountered similar problems.

In addition to this weakness, the military actions led to the destruction of a big part of the sewer system and its treatment plants, resulting in leakages into agricultural land. Sources of the Autonomous Administration agencies report that more than two-thirds of the treatment plants are either nonoperational or operate at an extremely limited capacity. However, the authorities have not drawn plans to address this weakness or build new plants, as they focus only on trifles, such as ornamenting the streets.

Many Syrians were forced to revive their old ways of cooking, washing, and heating. They deforested the remaining trees in gardens and streets, while the many mafias of the country took it upon themselves to destroy whatever was left of the forests and sidewalk trees, selling their wood for heating. At the beginning of the winter of 2022, the price of one ton of firewood reached 900,000 Syrian Liras (about $200).

In Al-Hasaka, as in the Syrian South, the wildfires of 2021 devoured the wheat seasons. The government did not heed the farmers’ calls for help despite hundreds of appeals that were submitted to the governor and the General Union of Peasants, and the sheep breeders were left alone in the face of the drought that hit the Syrian Desert during the same period.

In the regions of Idlib and the north and west of Aleppo, where the Turkish affiliated groups are in control, the situation does not look promising either. The issue of climate change takes a back seat as military and civil struggles rage among yesterday’s ‘revolutionary partners’. With the approval and support of the Interim Government, housing units are being built in the only region of Afrin that still has a small forest over an area of no more than few square kilometers. Simultaneously, logging activities continue in Jabal al-Zawiya, right before the eyes of the local authorities.

With poor rainfall, frequent droughts, and higher temperatures, people have become reluctant to engage in agriculture in the region that Syrians once called ‘Green Idlib’. Meanwhile, dependence on Turkish products, including bottled drinking water, has significantly increased.

Poor governance and weak planning are some of the factors that played a fundamental role in depleting local resources in the Syrian Jazira, Idlib, and the North and West of Aleppo, in addition to the mismanagement of water and the use of traditional irrigation methods that waste large quantities of water, while the existing authorities fail to give the issue the attention it demands.

Syrian civil society: faltering attempts

Civil society organizations and NGOs in Syria face numerous challenges that stem from the lack of official licensing and protection, all the way to the attempts to politically polarize them by the different dominant forces. This situation has prompted these forces to concentrate on the issues of relief and development and largely ignore climate change. The trends and concerns of these organizations match those of the international donors who, in turn, pay very little attention to problems related to climate change in the Syrian case. The organizations’ priorities are therefore ambiguous, and so are the ways with which they respond to the actual needs and crises on the ground.

No civil society organizations specialized in climate change issues have so far appeared in Syria. But, there are local organizations that work in partnership with international organizations to address some of the most pressing problems related to climate change, such as the problem of water shortages in regions whose resources were damaged or destroyed, such as the Jazira and Rif Halab (Aleppo countryside) among others. Nevertheless, these organizations were uninterested in teaching and spreading policies of sustainability and climate development, although some of them - mostly without the help of foreign funding – worked on the reforestation of the areas that were either caught in devastating wildfires or subject to cruel logging activities, such as the forests on the Syrian coast.

The Syrian Government was not the only authority that neglected taking necessary measures that should have been applied before, or even during the war. The authorities in Northern and Eastern Syria, as well as the so-called Syrian Interim Government (SIG) in north-western Aleppo all excluded climate change from their agendas. The environment and sustainable methods were overlooked, as were the relevant tasks.

There was no interest in water sustainability, recycling solid wastes, and afforestation, and most worryingly, no efforts were made to stop the outdated oil extraction operations in the regions of Raqqa and Deir el-Zor, or to stop logging activities in Rif Idlib.

In the regions under the control of the Damascus Government, civil society organizations, such as the Syrian Trust for Development, are licensed. In any case, the climate issue is nowhere on their agendas. A preliminary reading reveals that about 1000 civil society organizations all over Syria have failed to attend to the issue of climate change. The population remains suspicious of these organizations because their priorities and the issues they focus on seem distant from the people’s concerns. This failure has led to entrenching the existing traditional structures that do attach importance to sustainability and climate issues. Changing the status of the Syrian civil society organizations requires a strategic shift from a course focusing on supporting short-term individual projects to one that funds and supports long-term goals that address the most pressing issues, and based on partnerships that help climate-oriented capacity building.

How does Syria’s future look?

Dealing with climate disasters in Syria falls directly in the realm of the complications of the political scene in the country and its impasses. The Damascus Government tends to ignore the problems of the regions that fall outside of its control, and although problems such as droughts entail all parties, there is no coordination between the Syrian parties on climate issues. This non-cooperation affects the search for national Syrian solutions for the problems of climate change that harm everyone and do not discriminate according to political positions.

Most of these inadequate policies have driven Syrians - residents and displaced – to seek migration to Europe or to more stable, urban places in the country where people have always flocked after years of crop failure.

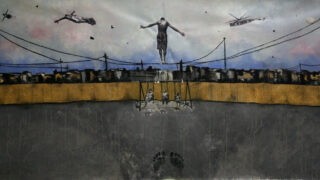

Unemployment, mismanagement, and many other problems have led to unrest (some of which had massive consequences, such as the protests of 2011) and could lead to the escalation of disruptions again. Currently, we are witnessing signs of intense migrations from areas hit by desertification and droughts to other areas that also do not provide decent living conditions, as many migrants arrive into slum areas where everyone is waiting for the slimmest chance to leave this hell.

After the outbreak of the civil war, the destruction of a large part of the infrastructure, the stifling of the minimum level of governance, and the decline of the historically sound Syrian agricultural sector, Syria has become more vulnerable than ever to future crises and shocks, including climate change and its impacts. The conditions necessary to engage in a more sustainable management have become less available. As a result, the ability to mitigate the multiplying climate risks has dwindled, which means that climate variability will play a greater role in shaping the outcomes of the conflict in the future.

Civil society organizations and NGOs in Syria face numerous challenges that stem from the lack of official licensing and protection, as well as the attempts to politically polarize them by the dominant forces. This situation has prompted these forces to concentrate on relief and development and largely ignore climate change.

Given the sheer amount of ruin, hunger, thirst, and desperation leading millions to attempts to flee the country any way they can – including the suicidal attempts at sea, and knowing that the entire world today is scrambling for energy and food amid conflict and unrest, while temperatures continue their frightening rise, it is evident that the Syrian war’s absurd continuation for more than ten years will not only affect Syrians today, but will also have more devastating consequences on future generations.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Ghassan Rimlawi

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 30/11/2022

1- https://bit.ly/3XYLVEn

2- A report dated October 21, 2021. https://bit.ly/3CwaqOe

3- https://bit.ly/3R8cFzY

4- https://bit.ly/3jcTEQn