This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

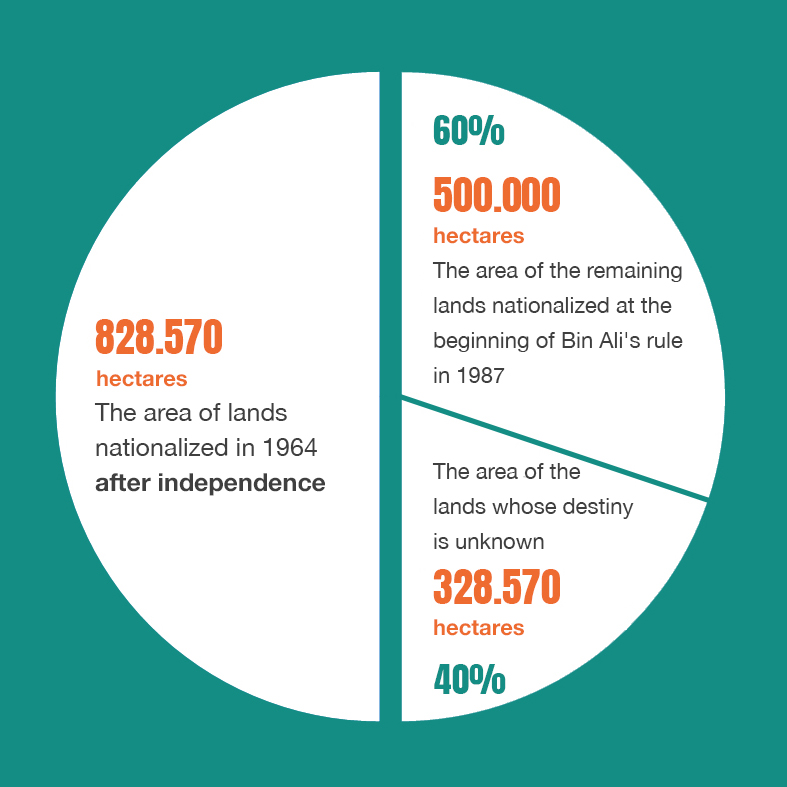

In May 1964, eight years after Tunisia’s independence, the lands that were seized by the French settlers during the colonial era were nationalized. Three years earlier, Tunisia was fighting the battle for the evacuation of the last French soldier from the country in October of 1961, and consequently, "real estate independence" was realized. The young, independent state became the largest owner of the lands known in the legal and political records in Tunisia as “state lands”, whereby the ownership of these lands is undisputedly monopolized by the state. The area of the lands nationalized in the sixties was approximated by the Institute for Strategic Studies to be around 828,570 hectares. However, this area was reduced in 1987, at the beginning of Bin Ali's reign, to approximately 500 thousand hectares.

No one in Tunisia knows exactly where the rest of the lands approximated at 328,570 hectares went. The issue of the management of state lands in Tunisia is a black box; numbers presented by the authorities are disparate and inaccurate.

Before the revolution, no one dared discuss the issue of these lands which were supervised by the State Land Bureau. Investigative journalism and in-depth scientific research are also very rare on this matter, for no other reason than the fact that it is a conflict zone between interest groups, most of which are concentrated in the regime's circles and close beneficiaries.

The liberal experiment (the period of Hedi Nouira’s rule 1970-1980) marked the beginning of the active economic exploitation of these lands by leasing all farmers’ lands to the benefit of an influential urban bourgeoisie. This trend was further reinforced by the 1969 Agrarian Structural Reform Law, a few months after the declaration of the failure of the socialist experiment led by, at that time, Bourguiba’s senior minister, Ahmed Bin Salah. The minister’s dream was to make Tunisia resemble a Scandinavian country, but his attempt failed, or rather, was thwarted, and backfired, resulting in further impoverishment of the countryside and a massive migration towards cities, which increased in the seventies and eighties of the last century in particular. The failure of the socialist experiment was mainly due to the issue of land itself, where the small and large landowners felt that the independence state was working on confiscating their lands and turning them into collective property-owned lands, which would take them back to the days of the “levying state”. At that time, the prevailing mentality was not ready to accept the notion of turning private lands into collectively owned lands, hence, the policy was faced with firm resistance.

The liberal experiment: Land at the center of the global division of labour

The liberal experiment launched by Hedi Nouira at the beginning of his rule, through Law 72 that supported the private sector, was a declaration of the integration of the national economy in the system of the global division of labour, in which priority is given to foreign investments whose production is directed mainly towards export. Foreign capital knows full well how to play the competitive game, relying on low wages and abundant labour. That is why it was drawn toward the agricultural sector which supplied cheap products, and whose trade routes are easily monitored. In this respect, the state lands had a fundamental role in altering the agriculture production market, whether on an internal level or in exportation.

State lands provide 20% of the agricultural products, especially with regard to basic products (milk, red meat, vegetables, and grains). On the other hand, these lands have significantly shrunk in area, as they were compromised through a policy of leasing and sales that was adopted as part of a system of concessions and the political economy of hegemony. Nobody knows to whom the licenses of the state lands were granted, nor what the criteria for leasing them were.

The experiment of self-management in the Jemna Oasis after the 2011 revolution has revealed that these lands were leased to those closest to the former regime. The family of the former president’s wife herself has grossly benefited from state-owned lands through the lease of the so-called agricultural villages (Day’at) and arable lands that were turned into a sort of real estate through the pressure from powerful lobbies. These lands would later be exploited in the frameworks of grand residential projects that devoured much of the agricultural lands in an illegal manner and without any clear urban planning.

Structural adjustment policy: Land in the plundering auction

After the first liberal experiment whereby the state relatively maintained a balanced role, Tunisia entered the globalized market economy in mid-1980s. Privatization expanded, and the role of the state diminished further. This time, also, the state lands acted as a prelude to setting up the basis of privatization through further concessions, be they sales or grants, supporting “revival companies”, reclamation, and agrarian reform to the benefit of agricultural engineers and technicians. All these actions were executed as smoothly and calmly as possible. It was a policy that was strengthened by taking a fundamental decision concerning how to deal with the state lands: leasing the lands on a large scale to the private sector (partly to agricultural engineers and partly to small farmers) and reducing the total area of state lands by selling some of them. This policy has contributed to the rapid increase of agriculture revival companies and the reclamation of state lands. To finance these companies, the government worked on establishing development finance banks that would be assigned the task of providing loans with the money funneled from Gulf investments (Saudi, Kuwaiti, and Emirati). This policy had relatively succeeded in creating some money flow that helped in establishing more companies. As a result, it deepened economic liberalization, which increased the greed for real estate capital. This is precisely where the economic liberal paradoxes in the countries governed by corrupted mechanisms emerged. Therefore, instead of the system stimulating production to create wealth, it turned to an entry point to the perpetuation of clientelism. Here, we are confronted with rentier liberalism, which is subject to the logic of “the gift”, in the anthropological sense of the word, that is, the creation of a relationship and a market for mutual benefits, governed by the equation that says "whoever takes must also give". And the price in this case was obedience and loyalty.

Investors and businessmen close to the president's family and beneficiaries of the government’s rent had seized several lands and agricultural villages. Even though those lands were confiscated after the 2011 revolution, no one yet knows the fate of the confiscated property.

Instead of the system stimulating production to create wealth, it turned into an entry point to the perpetuation of clientelism. Here, we are confronted with rentier liberalism, which is subject to the logic of “the gift”, creating a market for mutual benefits, governed by the equation that says "whoever takes must also give". The price in this case was obedience and loyalty.

The government was, therefore, distributing and allocating the lands, not in a purely liberal sense, but according to the logic of “gift economy”, which semantically refers to the logic of exchange prevalent in archaic societies. Figures show that about 12,000 hectares were granted to the president's family and those close to power.

It was President Bin Ali himself who had closely monitored the distribution of these territories. This was expected, as land is an authoritarian source of rent. It has an exchange value and is one of the means of practicing control and hegemony. The practice is not new in Tunisia; it dates to the era of the Beys (1), when the Bey used to distribute vast fertile lands (known in Tunisian dialect as Hanchir) to those closest and most loyal to him. Technically, the authorities grant or lease land according to a formal book of conditions, but most often, the rent dues are not collected. This continued to happen at the expense of the small farmers who were denied access to land.

The oppressive consolidation of power through land was particularly apparent in the Sminja region of Zaghouan Governorate, where one of Bin Ali's in-laws was granted more than 1,300 hectares. In 2010, an enormous project was inaugurated on that land that consisted of planting 1,200 olive trees with a high irrigation density (1,660 feet per hectare). Because of this project, the waters of Bir al-Mashariqah were depleted since all the water was diverted to these lands at the expense of small farmers in the region. Consequently, most of the farmers became wage earners after squandering their lands, whether by selling them or abandoning their exploitation and eventually migrating to the capital, Tunis, or to other major cities.

State lands: When real estate inequality prevails

Among the effects of the policy of leasing state lands, in addition to the fact that it came at the expense of small farmers, was the fact that it also contributed to the entrenchment of more corruption in the absence of monitoring and transparency systems. This is one of the cases of territorial inequality in the agriculture sector, especially in the hinterland areas where the larger areas of unexploited state lands are, in addition to an enormously high rate of poverty. This injustice led to the emergence of social claims and movements that held the slogan: "The right to land" that demanded that these lands be given to the farmers since, for several years, these lands remained uncultivated.

This dynamic of territorial inequality was absent from the discourse and did not receive the necessary academic attention as one of the factors that might have helped in understanding the Tunisian Revolution. The revolution had originated from the governorate of Sidi Bouzid, one of the governorates most reliant on the troubled agricultural sector, located in the center west of the country. In addition, this prevailing agricultural model is dependent on intensive irrigation, which has contributed to the depletion of the water table. This model yielded weak returns due to several factors, most notably the slim production routes of distribution in the local market, the state’s abandonment of small farmers, and the imposition of harsh conditions by the National Agricultural Bank regarding agricultural loans. On the other hand, the prices of fuel and agrochemicals soared, which contributed to further impoverishing the small farmers in the region who were left unsupported, at the mercy of the prices. While the farmers had to relinquish their lands at petty prices, opportunities were wide open for the investors who were given access to bank loans and facilities. Even loans provided by the Agricultural Investment Support Agency that were meant for the established farmers have been alternatively granted to businessmen. The rich have snatched everything away from the poor!

Most of the new landowners came from outside the governorate, and part of Sidi Bouzid's farmers turned into mere wage earners, as they did not meet the banking system’s criteria. The majority of them felt that their lands had been taken from them before their own eyes by an unjust banking system. Even worse, they have remained victims of the dominant stigma that they do not like to work and that they have voluntarily abandoned their lands! As a direct result of these farmers’ crisis, an army of "landless peasants" was created and fueled the revolution that overthrew Bin Ali. Under the banner of democracy, all of those peasants engaged in the debates on land disputes on several bases, the most important of which were the demands to achieve development and solve the widespread problem of unemployment in the hinterlands. The city of Regueb in Sidi Bouzid governorate, known for its fertile farmlands, witnessed strong social movements as unemployed young men with university diplomas demanded to be granted lands that they could work. The fact that the lands they were demanding were state-owned reinforced local resistances. A short film made by a young man in Regueb documenting chronological events of the revolution shows a scene of a protest rally in solidarity with Sidi Bouzid in front of the National Agricultural Bank on 24 December 2010. The next day, the bank's ATM was set on fire.

While the farmers had to relinquish their lands at petty prices, opportunities were wide open for the investors who were given easy access to bank loans and facilities. Even loans provided by the Agricultural Investment Support Agency that were meant for the established farmers have been alternatively granted to businessmen.

The rich have attacked the poor! Most of the new landowners came from outside the governorate, and part of Sidi Bouzid's farmers turned into wage earners, as they did not meet the banking system’s criteria.

The state lands have been the focal point of these disputes. The Meknassy region locals in Sidi Bouzid Governorate demanded to be given Nasr Village, an estate owned by the state, by altering its property description and referring to the Land Register to be able to exploit it. This village was granted to anti-colonial militants by president Bourguiba in 1974 as a token of gratitude, but it remained registered in the name of the state which created a problem that hindered its agricultural exploitation.

Also, some of the collectively owned lands in the Meknassy region, were tuned into state properties after the failure of the solidarity experiment in the late 1960s. However, not correcting the lands’ legal status created disputes between families and local groups that consider that these lands’ ownership belongs to them and that they have the legal right to exploit them on the one hand, and between local authorities that consider this appropriation to be an infringement on state property on the other hand. Local residents wanted to repeat the Jemna self-management experience, but they were firmly dismissed by the authorities. The official apprehension stemmed from the fear of a “socialist model” that contradicts the neoliberal choice that believes that agriculture does not stand a chance outside the logic of a market economy and financial flows. Within this framework, the ALECA agreement with the European Union demands more “liberalization” of the agriculture sector.

These conflicts that escalated after the revolution revealed that there is a wager on the land, particularly in Sidi Bouzid, and the rest of the hinterland regions in general. It further revealed the relationships between the local residents and regional institutions which gave priority to the sectors with promising economic potential. Moreover, keeping conflicts regarding access to land without clear solutions can sometimes escalate these issues into tribal and ethnic conflicts.

Land is much more than a commodity which has exchange value; it is more than a means of ownership and accumulation. Ultimately, it is one of the components of collective identity, family heritage, and ancestral history, which embody a sense of belonging synonymous with feelings of honor. The conflict over the “right to land” is, hence, multidimensional.

Revolution and state lands: Renationalization

The achievement of the revolution might well be that it has put the policy of disposing of state lands into question. This is no small feat, and the protesting movements, vying for the right to land, have embodied this issue. As such, scholar Mohamed Elloumi argues that it relates to the "internal occupation" imposed by the urban bourgeoisie on these lands, after they had been occupied by French settler colonialists. It was suggested that the lands be nationalized again, on the basis of social justice.

At the beginning of the revolution, local residents seized these lands. About 100 agricultural villages (Day’at) – the Maghreb term for concentrated agricultural lands – were attacked, and the subsequent losses were estimated at 30 million Tunisian dinars. These villages were owned by the family of Bin Ali's wife and those close to them. The post-revolution governments worked on retrieving some of these villages, citing mismanagement, but until now, they have never seriously considered redesigning the management policy for the state lands. It looks like successive post-revolution governments do not know what to do with their real-estate capital. As for the Convention for the Liberalization of the Agricultural Sector intended to be signed with the European Union, it once again clears the way for the abandonment of state lands under the slogan of "supporting foreign investment" and achieving growth. The consequences of this trend will be more poor people and the exacerbation of tension based on the "right to the land".

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Ghassan Rimlawi

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 18/04/2019

1- A Turkish word that means the prince. Originally, the Bey was the Tunisian Wali (ruler), the representative of the Ottoman state, headquartered in the city of Tunis. At a later stage in the Husseinite era, he ruled independently from the Ottomans. The first Bey was Hussein Bin Ali, the founder of the Husseini State in the year 1705, and the last was Bey Mohammed al-Amin. Beys’ rule was monarchical and hereditary and lasted for 252 years. It ended with the founding of the republican rule on 25 July 1957.