This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Ytto is the name of a Berber woman fighter who resisted French colonialism and was martyred in the Battle of El-Herri. Her name and the story of her struggle have remained obliterated and ignored, unlike those of the resistance men whose names and exploits have been known and told over the years. Ytto Foundation has revived her exploits by consciously choosing to carry this forgotten resistance fighter's name, stating that ignoring her name is an intolerable violence against women and their overall movement.

This was the starting point for Ytto Foundation for the Sheltering and Rehabilitation of Women Victims of Violence. It is a non-governmental organization that adopts an approach of participatory fieldwork with women and the population in general, especially in the remote and marginalized areas of Morocco. It was founded in 2004 by a group of activists interested in women's rights and social work. Its activity revolves to a large extent around social convoys that go to villages and outskirts. The Foundation is also present at a field level, holding workshops to develop women's capacities to advocate for their various issues.

Activist Najat Ikhich, who has worked on political, syndical, and women's rights issues for over 45 years, chairs the Foundation. Over the span of her career, she has co-formulated a set of proposals to amend the Personal Status Law in Morocco and participated in establishing several women's associations.

Ytto's approach to fieldwork

The Foundation chose a path Ikhich has described as tiring but pragmatic. Ytto adopted grassroots fieldwork and resorted to a participatory approach with women, not only in major cities but also in very remote villages that suffer from precarity, exclusion, and marginalization. Undoubtedly, these conditions affect everyone, but they doubly affect the women of these communities. As Ikhish puts it, the Foundation's fieldwork aims to "liberate the women's word" as a preliminary precondition, and to assist them in moving from victimhood to a position in which they have the agency to suggest ideas and affect change.

Ytto Foundation for the Sheltering and Rehabilitation of Women Victims of Violence was launched in Morocco in 2004. It focuses its work on remote and marginalized areas, in particular, reaching them by organizing and sending convoys which establish participatory fieldwork with women and the population as a whole. The foundation’s name, Ytto, is an homage to a Berber female fighter who resisted French colonialism and was martyred. However, her name and the story of her struggle remained obliterated and ignored.

The Foundation returns to the remote areas and villages visited by the convoy to follow up on the work. It does so by holding workshops to strengthen women's capabilities and train them on how to advocate, arrange meetings, and prioritize demands. Because one group cannot bring about extensive change, the performance of these workshops automatically moves to the level of networking. In other words, they establish women's networks between different villages that allow them to progress to the stage of advocating for multiple causes, formulating proposals, and writing demand files.

The role of the Foundation is not limited to facilitating “cathartic” sessions for women to express themselves, their concerns, and their anxieties. “A subordinate individual cannot effect change. The person who is capable of change is the one who believes that his/her role in the process of change is absolutely crucial. These people are always moving forward towards changing themselves,” Ikhich said. "Workers in women’s foundations are not supposed to become the guardians of women or make decisions for them. On the contrary, what is most important is that the suggestive and creative force springs from these women themselves who take center stage, while the foundation walks behind them, supporting and assisting rather than leading and patronizing," she explained.

Convoys and workshops

Between 60 and 100 female and male volunteers of various ages participate in the annual social convoys organized to go to marginalized and isolated areas. They go together to dismantle the isolation of these areas and help give their women a voice. Several workshops are held during these convoys, one of which is called “Women, you have a voice. Express yourselves. Decide for yourselves.”

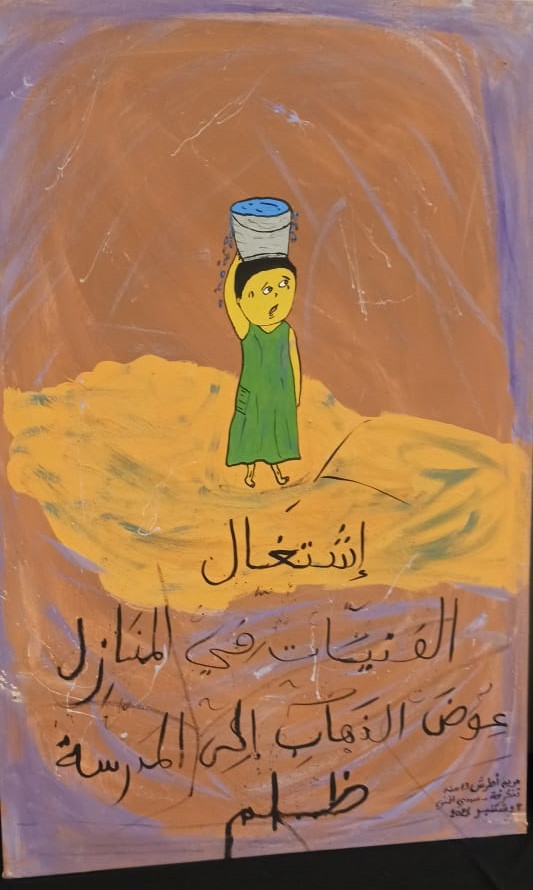

In Morocco: Women Draw Light out of Darkness

06-07-2022

Sulaliyyate Women in Morocco: This Land Is Ours

16-07-2022

Women's speeches during these workshops turn into something of a group therapy, as women often choose to begin by talking about their personal experiences and collective sufferings within their communities. After sharing their concerns, the question is raised: "Do women want to move from the position of the “woman who suffers” to the position of “the woman who invests in the potential of her area for the benefit of herself, her village, and her community”?" This question stimulates thinking about solutions to the multiple issues that preoccupy women: “Why do I have to fetch water every day from a faraway well when in other areas there is tap water available at fingertips?” or “Why can’t I go to school?” or “Why am I forced to marry at such a young age?”, etc. These are urgent questions that animate debates and stimulate action.

“When they did not allow us to enter a school or dispensary to do our work, our convoy did its work from the street. They could have sent someone to arrest us all, but the residents, both women and men, knew that we were there to help them, so they, in turn, came to our aid. Sometimes the people would open up the mosques for us, which we entered without wearing headcovers.”

Women are aware that casting their ballots to elect members of municipalities, parliament, and the government does not mean they have wielded the power to find or implement solutions to the problems that concern them as women. They conclude they are second-class citizens rather than citizens with full citizenship rights, and they realize that they have to take action if they wish to become full citizens.

"But how do we act?" It appears that the answer is "by applying pressure." Then another question follows: “But should we apply pressure as individuals or as groups?” Thus, the discussion develops to crystallize the idea that collective pressure is the best way to achieve effective solutions to the problems of society and women.

Demands-based files

What after the convoys? Ikhich answered: "The Foundation returns to the remote areas and villages visited by the convoy to follow up on the work. It does so by holding workshops to strengthen women's capabilities and train them on how to advocate, arrange meetings, and prioritize demands as they see fit."

Because one group cannot bring about extensive change, the performance of these workshops automatically shifts to the level of networking. In other words, they establish women's networks between different villages that allow them to progress to the stage of advocating for multiple issues, formulating proposals, and forming demands-based files.

Workers in foundations are not supposed to become the guardians of women or make decisions for them. On the contrary, what is most important is that the suggestive and creative force comes from these women themselves who take center stage, while the foundation walks behind them, supporting and assisting rather than leading and patronizing.

Women are aware that casting their ballots to elect members of municipalities, parliament, and the government does not mean they have wielded the power to find solutions to the problems that concern them as women. They conclude they are second-class citizens rather than citizens with full citizenship rights, and they realize that they have to take action if they wish to become full citizens.

Ytto is keen that the demands-based files include two core components. The first is of particular interest to women, such as issues of girls' education, child marriage, and economic empowerment, which is very important for women. The second component has to do with demands that concern the entire population, including men and the youth. According to Ikhish, breaking the isolation of these marginalized communities means creating a better life for both their men and women. Therefore, Ytto Foundation also engages in helping to establish cultural, environmental, and social associations for men.

Indeed, there are various difficulties and obstacles in the path of women's social and public work, but the successes surpass them. In an interview via Zoom with Assafir Al-Arabi, Najat Ikhich recalled how the Foundation has used a theater performance in one village to bring young girls up on stage during a play. The girls voiced their opinions openly to the village’s men and to their fathers, speaking frankly about their suffering and what it meant for them to be pulled out of school when their peers in the neighboring towns and villages enjoyed the right to education. Their words, sincere and unwavering, were of enormous impact, resulting in reinstating 25 girls from the village to school.

Overcoming obstacles and supporting the community

Regarding the difficulties and obstacles posed by the authorities, Ikhich said that their work is never without thorny hardships. She recalls how one village was staunchly resistant to Ytto’s fieldwork. "Those who oppose our work are well aware that we are building an alternative society in which inequality will be abolished. Officials' desire to maintain power leads to their resistance to change." She added: “For example, the governor of a certain region might say: ‘Your convoy shall not pass through the land of my governorate,’ and this is because he knows that the convoy carries a democratic community project.”

The demands-based files include two core components. The first is of particular interest to women, such as issues of girls' education, child marriage, and economic empowerment, which is very important for women. The second component has to do with the demands that concern the entire population, including men and the youth. Breaking the isolation of these marginalized communities means creating a better life for both their men and women.

Women activists often use dialogue and negotiation with opponents to remove confusion and ease fears. But if all fails, they are left with no other solution than to impose their presence. “When they did not allow us to enter a school or dispensary to do our work, our convoy did the work from the street. If they wished, they could have sent someone to arrest us all, but the residents, both women and men, knew that we were there to help them, so they, in turn, came to our aid. Sometimes the people would open up mosques for us, which we entered without wearing headcovers.”

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabry Zaki

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 03/07/2022