This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

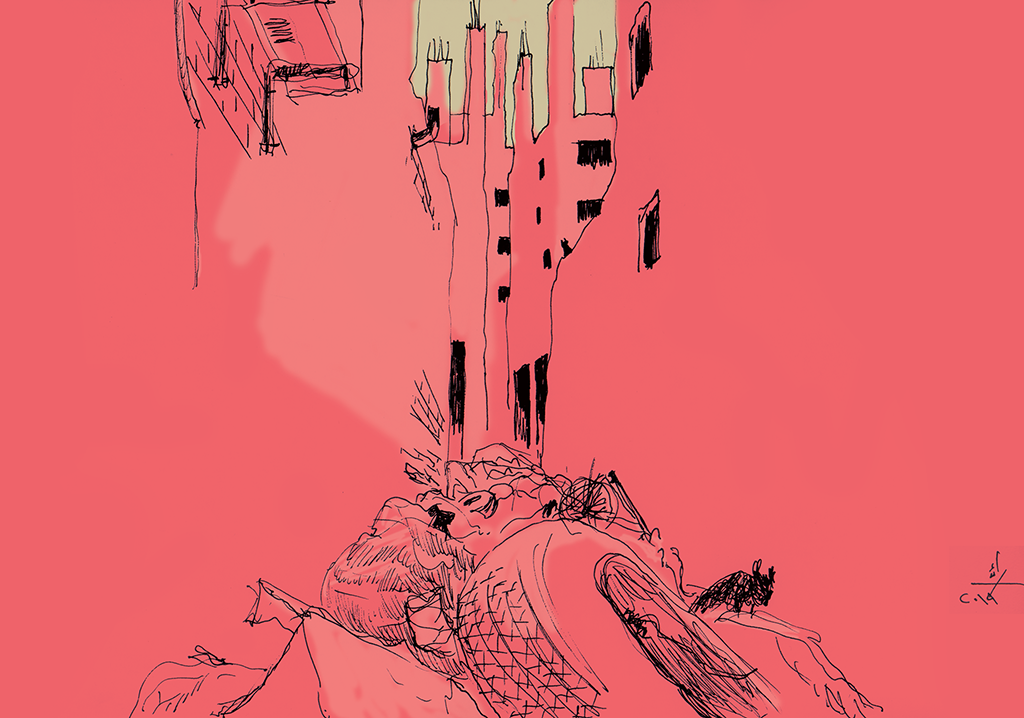

Many a sad Iraqi song talks about home and residence. The notion is so important to Iraqis that many of them refer to their privately-owned place of residence as their "homeland." Each generation advises the next one to tighten the belt and spend less money so that they could “buy themselves a homeland” that shields them from the evils of the heat, cold, and landlords; a ruthless mixture of harsh climate and cruel people that Iraqis find themselves up against. Obtaining ownership of a home in Iraq, especially in the capital, Baghdad, is a back-breaking endeavor. As a result, the demand for housing is high, while the supply is scarce and extremely expensive. Hence, the greater the need for housing, the greater the area of slums in Baghdad.

The history of informal settlements in Baghdad

For more than a century, urban planning architects failed to anticipate the population growth in Baghdad. The speed with which Iraqis have been moving to Baghdad for work has always surpassed that of the architects' pens as they tried to map out Iraq's capital and designate its borders. The German engineers Brecks and Bronoweiner were the first victims of the urbanism of the Round City of Baghdad, bordered by Abu Jaafar al-Mansur with cotton and fire. They tried to draw up a plan for Baghdad in 1936 to accommodate half a million people within two decades instead of the quarter of a million population at the time. However, only a decade had passed when the population growth had already exceeded the architects' expectations. The same thing was repeated with Minoprio & Co. in 1954, which predicted that the population of the second-largest capital in the Arab world would reach a maximum of one and a half million in 2006 (1). However, it only took ten years for Baghdad to reach this number of inhabitants. The case was repeated with five other international architecture firms (2) , with none succeeding in taming Baghdad or predicting its population, which today exceeds 8 million people.

Basra and Mosul had competed with Baghdad for hundreds of years as central cities in Iraq, but the establishment of the modern Iraqi state in the 1920s consecrated Baghdad as the capital city and as a political and economic center which lured many of the significant families to move there, or at least to send their children to study in the city. The establishment of the modern state required bureaucratic, military, and civilian agencies, which opened the door for employment wide in the capital. This laid the basis for the emergence of the first informal settlements in the 1920s to be inhabited by the lower ranks of the military and daily wage laborers (3) . However, the presence of these slums in limited numbers on Baghdad’s urban fringes hastened the need to find solutions to address them.

For more than a century, urban planning architects failed to anticipate the population growth in Baghdad. The speed with which Iraqis were moving to Baghdad and for work has always surpassed that of the architects' pens as they tried to map out Iraq's capital and designate its borders. Today, the city’s population has exceeded 8 million.

Baghdad, which lured the arrival of the bureaucracy and feudal lords from the various governorates, was, at the same time, oppressing the peasants of the southern cities due to its royal authorities' collaboration with feudalism. The oppression of feudalism led to massive migration to the fringes of Baghdad, where the first crowded slums in the capital were established.

At the end of the 1930s, the farmers coming from southern Iraq established Al-Saraif [houses made of reeds and palm fronds] in the eastern and northern urban fringes of Baghdad. Moreover, the farmers fleeing the oppression of feudalism and seeking a new life established new informal settlements, with an estimated population of 184,000 in 1958. It was the year that witnessed the establishment of the republican system and the rise of General Abd al-Karim Qasim to power.

Qasim quickly approved housing projects that established the cities of Al-Thawrah (currently Al-Sadr), Al-Shualah, Al-Kamaliyah, and Al-Fadiliyah. The government distributed the housing units in these cities among the slum dwellers and the displaced from the central and southern cities (4). Qasim's move still raises a sharp division between supporters and opponents, as the slum dwellers, at that time, constituted about 18% of the capital's population, which was the first step in the ruralization of Baghdad. On the other hand, these displaced people constituted about 57% of the workforce in the capital, which means that they quickly integrated into the city and contributed to the development of its economy.

Baghdad continued to be an increasingly central city during the republican era, which witnessed coups and political unrest that led to a fluctuation in the government's performance in developing the governorates' economies. Consequently, the migration to Baghdad continued, and new informal settlements started to grow. However, successive governments were quick to settle the legal status of slum dwellings, whether by granting them title deeds, organizing them in return for small amounts of money paid by their residents, or by demolishing and finding housing alternatives for their residents based on the nine decrees and laws issued between 1959 and 1989 (5) .

Although all these laws and decrees have settled the legal conditions of the slums, they have not led to a fundamental solution to the housing crisis that Iraqis have suffered. The housing shortage increased because Saddam's regime was preoccupied with fighting wars and directing public financial budgets to strengthen and develop the military system.

Since the mid-1970s, the Iraqi middle class has been trying to devise ways to overcome the housing shortage by dividing large houses and designating parts of the house for their sons to live in or as work spaces. The growth of the number of family members and the children reaching the age of marriage meant it was time to build a new residential unit atop one part of the house. Residences of a surface area of 200 square meters or more have gradually transformed into three homes and a small shop in some cases, by building in the garden, canceling the car garage space, and separating the second floor of the house, turning it all into homes for the family’s younger generations.

With the advent of the 1990s, unemployment soared, the dinar price fell to the lowest level, and the private and public economies were destroyed due to international economic sanctions on Iraq. All this meant the absence of any housing plans.

More than half of Baghdad's population lived below the poverty line in the 1990s. However, the capital's political and economic centralization prompted those plunged into poverty to migrate from other governorates to it. The newcomers formed new informal settlements on Baghdad's southern and northern outskirts. No accurate statistics are available on the size of informal housing in that decade. However, the official departments registered more than 12,000 requests (6) to regularize the status of informal housing.

US occupation and growth of informal settlements

After the US forces occupied Baghdad in April 2003, the housing crisis became evident in Iraq, which Saddam Hussein's iron-fisted regime had controlled through military rule and the imposition of strict measures. It is worth noting that Iraq is suffering from a growing housing shortage, estimated at 2.5 million housing units. Baghdad is at the top of the cities that suffer from an increasing housing shortage due to the considerable population increase and the continued migration from other governorates. Since 2003, the desire to own a place of residence has not been limited to one social group. In a silent deal, parties and destitute people have shared the ruins of the Baathist state, as the poverty-stricken families quickly moved to seize homes, department buildings, and lands belonging to the state. Some families settled in former government buildings and converted them into apartments. Meanwhile, the parties and their members coming from the diaspora rushed to seize the palaces, homes, and lands owned by the leaders of Saddam Hussein's regime. The citizens gave the lands and buildings they took over the name of “Al-Hawasim,” in a sarcastic reference to Saddam Hussein's naming of the last battle of Baghdad the "Battle of Al-Hawasim" (“The Decisive Battle”); that battle led to the occupation of Iraq in one month’s time, while Saddam’s propaganda insisted that the invasion would lead the US forces to commit suicide at the gates of Baghdad.

On top of that, there have been no plans to develop housing and bridge the wide gap between supply and demand for housing units. This is in addition to the emergence of a new class of party members and party-affiliated merchants with an enormous appetite for real estate, which has led to an insane rise in housing prices. Therefore, housing prices in Baghdad, which is on the list of the worst livable cities, are now competing with the prices in the most expensive Western countries. Although the Iraqi Constitution laid the foundations of the free market and neoliberalism concepts in Iraq, it has recognized the state's responsibility to provide housing for citizens (7), evidently tickling the feelings of the Iraqis and their basic need for shelter. However, some entities have taken advantage of this need later, away from the constitution and the state authority. When some militias found out that informal settlements were an easy way to profit, entire slum areas were built after armed factions divided state-owned lands and sold them to Iraqis. With the protection of the militias themselves, these lands were also used to build housing units of varying sizes. This trade has led to numerous conflicts and even assassinations among the militias for control over land. The disputes became public when Muqtada al-Sadr, the leader of the Sadrist movement, issued statements to condemn members of his movement who trade in state-owned lands, ordering them to relinquish these lands.

However, little was achieved in this regard, and those whom al-Sadr had expelled quickly found a place for themselves in other armed factions.

In a silent deal, the parties and destitute people have shared the ruins of the Baathist state since 2003. The poverty-stricken families quickly moved to settle in homes, departments, and lands belonging to the state. Some families settled in former government buildings and converted them into apartments. Meanwhile, the parties rushed to seize the palaces and land plots of the leaders of Saddam Hussein's regime.

If political parties and their collaborators have taken advantage of the population's need for housing to make profits, they must have also taken advantage of this need for political gains. From 2003 onward, the authority has played on the nerves of slum dwellers, exploiting their need for housing by threatening them with strict legislation and decrees aimed at demolishing and removing slums and compensating their residents with small sums. The threats have provoked terror among the poverty-stricken residents, causing a whirlwind in the media about the slums' poor and the lack of a residential alternative.

When it had become a matter of public opinion, officials rushed to reap the fear they had planted by visiting the slums and promising their residents to stop implementing the removal decisions until solutions to their problems are found. In this way, the slums have turned into a bazaar for politicians to promote themselves by expressing words of mercy toward their residents. Many MPs and officials won the votes of slum dwellers by promising that they would pressure the government to prevent the demolition of their homes, give them title deeds to land lots, and deliver utility services to their areas. They also used promises of distributing land to citizens as one of the ways to get votes in parliamentary elections. Several MPs promised to provide housing lands to their voters if elected to Parliament.

On the other hand, the executive authorities distributed several land lots to some union groups and to the poor. However, the distribution of the majority of these estates was merely done on paper, as the executive authorities did not define their boundaries. In addition, the municipality did not include them in urban planning to start construction and resolve the housing crisis. Over the past decade, no government program presented to Parliament was without promises of solving the housing crisis and distributing land to citizens. The Councils of Ministers issued several decrees in this regard, such as the decrees issued by Prime Ministers Nuri al-Maliki, Haydar al-Abadi, and Adil Abd al-Mahdi. However, these decrees, which reproduced one another, did not go beyond the social media websites through which they were announced.

Many MPs and officials won the votes of slum dwellers by promising that they would pressure the government to prevent the demolition of their homes, give them title deeds to land lots, and deliver utility services to their areas.

Successive governments and the parties that formed them were the cause of the emergence of informal settlements. It is not only because of corruption and the lack of housing plans, but it is also because of the direct participation of these governments in the expansion of slums. These governments and parties have taken advantage of the citizens' need for housing to achieve financial and political gains. On the other hand, slum dwellers realized that politicians needed their votes, so many began negotiating for services in exchange for voting in elections.

Slum communities and their economy

Since 2003, informal settlements have been expanding increasingly. The slums seemed to be a paradise for those in need of housing, and they began to develop and grow very quickly. None of the 16 municipalities in Baghdad are free of slums, as the population of slums in Baghdad alone is about two million people. Also, the number of informal housing units in Baghdad is 136,689, which constitutes about 26 percent (8) of the number of all housing units throughout Iraq. Baghdad, thus, ranks first among all other Iraqi governorates.

The governorates and the outskirts of cities have gradually turned into places that expel their residents after the collapse of agriculture, the extinction of small industries, and the concentration of the labor market within the cities. It is in addition to the absence of fair rent laws and bank loans, the destruction of public transportation, and the placement of suffocating checkpoints at the gates of Baghdad. It made moving between cities and their outskirts expensive and arduous, not to mention moving between governorates.

Accordingly, most slum dwellers in Baghdad are day laborers who earn a non-fixed income from working in construction and porterage, as well as workers who make money from the concrete block and brick factories. Some slums were established next to these factories because they provide a semi-fixed source of livelihood, albeit low in income, for migrants coming from Baghdad or other governorates.

The markets for buying and selling land lots have expanded in slums; their homes and land lots are circulated on the Internet and in real estate offices. They also have contractors who provide financial services such as installments for construction costs. Many poor families, even middle-class families, are resorting to slums instead of paying about half of their income for rent. Thus, the slums have become affordable "homelands" that can be inhabited instead of the houses that fall within the planned urban cluster of the city of Baghdad, which requires a financial miracle. It needs about 20 working hours per day for a decade or more for a person to buy a house with an area of 100 square meters or less.

This situation might explain the contrasting scenes in some informal settlements. For example, you can see houses built with luxurious designs and cars whose prices exceed $50,000 parked right next to them. So how come such an affluent person lives in an area with no utility services? There are many explanations for this phenomenon, some are economic, and some are social. From the economic point of view, one cannot get, for example, a house with an area of 200 square meters or more in the licensed areas for less than $1,000 per square meter. Meanwhile, the price in slums built on agricultural lands drops to about $200 per square meter or less. Thus, the area of the house compensates for the absence of utility services.

The markets for buying and selling land lots have expanded in slums; their homes and land lots are circulated on the Internet and in real estate offices. They also have contractors who provide financial services such as installments for construction costs. Many poor families, even middle-class families, are resorting to slums instead of paying about half of their income for rent.

Informal settlements in Baghdad did not develop in one specific form. Some were built on plots of land without title deeds; 98% of which are state-owned and 2% are private property. Other types of slums were established outside the urban cluster of Baghdad by converting agricultural lands into residential areas. These land lots were planned by architects, most of whom work in municipalities, in return for a bribe or a share of the land. The farmers sold some pieces of land to realtors who collaborate with the authorities; they then divide the estates and resell them after connecting them to basic utilities such as water and electricity. Sometimes, they help build modest schools and clinics for the purpose of raising the price of land.

Shantytowns built in Baghdad constitute a small percentage of the informal settlements built with brick (48%) and those built with concrete blocks and cement (44%) (9). The slum dwellers have invested everything they own to build a house that they seek to develop whenever the opportunity arises. They usually put the house structure for the first floor without brick or concrete block cladding. The housing development process -- whether the facades are beautified or a second floor is built -- depends on the size of the family and the number of married couples in it. The average number of people living in an informal housing unit is seven. Families in these slums grow rapidly due to kinship relations among the residents, which depend on tribal customs to run their affairs. Hence, early marriages and high birth rates are main features at slum dwellings. There are no statistics that show the percentage of slum dwellers' access to education or the number of schools. However, the residents have innovated ways to provide some of their essential services. They built simple schools by collecting donations and made agreements with the Ministry of Education to provide them with teachers, and they opened small clinics where nurses provide healthcare, taking on the role of general physicians. Due to adherence to tribal customs and traditions, there is no need for police stations to resolve legal and security matters among the residents.

Kinship relations play a leading role in the emergence and expansion of slums, as clans encourage their members to move in to their neighborhoods to form an area inhabited by relatives. There are areas in which the proportion of the population of the same clan is about 60% (10). They show solidarity and help each other in good times and, especially, in bad times. Protection from conflicts with other clans is one of the reasons why some well-off clan members have moved in to slum areas. The clan’s protection is an enormous source of power, as members might go as far as sacrificing their souls for each other in a potential affray with other clans.

Maps of Deprivation and Dissolution in Iraq

20-08-2015

Of course, some informal settlements, such as those in Muaskar al-Rashid, contain various groups of social outcasts such as sex workers, gypsies, and gangs specializing in theft and kidnapping. Those people have obtained the protection of armed factions to continue their trade. On top of that, cooperation arose between these social groups and armed factions based on their need for mutual services. For example, brothels provide evening parties for the lower-rank leaders of the armed factions in exchange for protection from the dangers of other groups neighboring them in the slum, as well as protection from the authorities’ crackdowns.

The residents have innovated some services. They have built low-cost schools by collecting donations and making agreements with the Ministry of Education to provide them with teachers. They also opened small clinics where nurses provide healthcare, taking on the roles of general physicians. Due to adherence to tribal customs, there is no need for police stations to resolve legal and security matters among the residents.

Illegal acts are not limited to slums; they are widespread in all Iraqi cities, even in city centers. Many academic studies that warned of the “security dangers” lying in slums due to the trades of drugs and human organs seemed to be a media blackout.

Kidnapping gangs have been operating comfortably and sharing ransom amounts with some armed factions. At the same time, they have provided their services by assisting the armed factions in kidnappings and harboring the kidnapped persons. Over 16 years, the government has talked several times about evacuating Muaskar al-Rashid from its residents. However, the topic quickly faded, firstly because no alternative housing units were established for these groups, and secondly, because the armed factions that have members in the government and parliament did not want to eliminate their haven of illicit activities, which shields them from any social criticism. It is in addition to the fact that they are not afraid of the authorities, as they are part of them.

However, illegal acts are not limited to slums; they are widespread in all Iraqi cities, even in city centers. Many academic studies, which warned of the “security dangers” lying in slums due to the trades of drugs and human organs, seemed to be a media blackout, particularly when they relied on the similarities between Iraq's slums and some of Egypt's. This approach led these studies into the traps of stereotyping and ready-made conclusions, as they failed to examine the reasons leading to the emergence of slums, the social kinship dynamics inside them, or even the differences in the nature of security practices between Iraq and other countries.

On the other hand, many government statements and press reports have attempted to demonize residential slums as areas that represent an exceptional case in Iraqi geography and urban style. They accused slums of weighing down on utilities such as electricity and potable water networks. However, this seemed, for the most part, to stem from the authority's need to justify its failure to remedy the tremendous population growth and solve the housing and services crisis. Therefore, the slums became the perfect scapegoat on which all the service and utility shortages are blamed.

Alternative homelands?

The “homelands” created by slum dwellers seemed convenient as long as they guaranteed that the government and its parties would win votes in elections and gain money by selling land. This situation continued for more than 15 years. Then, the political trajectory of the ruling parties changed and their lust for money increased even more in light of their efforts to perpetuate the regime established after the occupation of Baghdad in April 2003.

The 2018 parliamentary election brought about a political shift. It led the ruling parties to change their clientelistic approach in dealing with the population, giving people crumbs in exchange for control over politics, resources, and the public sphere. This election witnessed a massive abstention, estimated at more than 70% of the electorate. Despite this, the parties agreed to form a government without specifying the largest bloc within Parliament - a deal that violates the constitution. As a result, Adil Abdul Mahdi, who did not even run for the election, became Prime Minister. Thus, the parties felt that they no longer needed the people.

It was a green light for the ruling parties to carry out its projects with complete disregard to the population, starting with the plan to demolish slum dwellings in Baghdad and the governorates and remove street vending stations.

Thus, since the summer of 2019, campaigns to remove slums began in Baghdad and the central and southern governorates. The declared reason for the campaign was the regulation of the urban model, while the ulterior motive was regaining control over the state's lands to reinvest them in commercial and residential projects (11) .

The parties felt that they no longer needed the people, so they formed the government outside the constitutional rules. 70% of the electorate abstained in the 2018 elections. It was a green light for the ruling parties to carry out its projects in complete disregard to the population. These projects were to demolish slum buildings in Baghdad and the governorates and remove street vending stations.

For example, the government is planning on turning Muaskar al-Rashid to something like Mataar al-Muthanna, which the government granted to an Iraqi investment company affiliated with an entrepreneur close to the Shiite parties in the country. The investor would then build a residential complex where the price of a housing unit ranges between $225,000 and $340,000.

Despite facing violent resistance from the residents, the Baghdad Municipality has managed to remove about 3% of the slums in Baghdad by the end of September 2019. At the time, some political forces called for accommodating those whose homes were demolished. Feeling humiliated and oppressed, the slum dwellers participated in the demonstrations that started on the first of October 2019. Consequently, the issue of slum dwellings was rekindled in political corridors and in Parliament discussions with a soft discourse that affirmed the people’s right to housing and a dignified life. Nowadays, more than one proposal is being considered to give them title deeds instead of an earlier proposal that suggested leasing the land to the residents for a period of 25 years. However, those proposals are far from convincing for the slum dwellers who remain at the front lines of demonstrations and sit-in squares in Baghdad and the other governorates. It seems that the slums are no longer enough of a “home” for those people, which is why they were ready to participate in protests where some of them were wounded or killed while carrying banners with the slogan: "We want a homeland."

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabry Zaki

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 05/12/2019

[1] Muhammad Jasim al-Ani and Zahra Kamel Kazem al-Kinani: “The City of Baghdad: An Analysis of the Mechanisms of Economic Action in its Origin and Development,” Journal of the Plan and Development, Issue (19) 2008.

[2] Muhammad al-Tai: “Baghdad in a Century of Basic Plans,” Al-Adab magazine, issue (113) 2015.

[3] Intizar Jasim Jabr and Shuruq Naim Jasim: "Developing the urban environment for slums - The city of Baghdad as a model," Journal of Geographical Research, issue 23, 2016.

[4] Muhammad Ali Mirza: "Settlements of Encroachment in the City of Baghdad and its Geographical Dimension," Journal of the College of Basic Education, Issue (191) 2008.

[5] Hashim Jaafar Abd al-Hasan: "Treatment of Informal Settlements within Sound Planning Standards," the Iraqi Journal of Market Research and Consumer Protection, Issue (1) 2013.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Article (30) of the Iraqi Constitution: “Second: The State shall guarantee social and health security to Iraqis in cases of old age, sickness, employment disability, homelessness, orphanhood, or unemployment, shall work to protect them from ignorance, fear and poverty, and shall provide them housing and special programs of care and rehabilitation, and this shall be regulated by law.”

[8] Ministry of Planning: “National Development Plan 2018-2022”

[9] Jamal Baqir Mutlaq and Hayder Razzaq Muhammad al-Shubr: (Identifying proposals to solve the problem of informal housing / an analytical study of the city of Baghdad for the period from 2003 - 2008), Journal of the Plan and Development, Issue (33) 2016

[10] Muhammad Ali Mirza: "Settlements of Encroachment in the City of Baghdad and its Geographical Dimension," Journal of the College of Basic Education, Issue (191) 2008.

[11] Telephone conversation with a political source.