This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Iraq is intent on vaccinating 20% of its population over the age of 18 by the end of this year, according to a government plan that was initially aiming at reaching a 70% vaccination rate. However, and despite the fractional target percentage, the goal seems unrealistic in light of the deficient national health sector, the lack of confidence in it due to its failure to contain COVID-19, repeated hospital fires, skepticisms about the effectiveness of vaccines, and the widespread corruption.

Studying the hypothetical target number of vaccinations that Iraq is trying to reach before the end of 2021, relative to its 41,190,658 citizens, and in comparison with the limited number of doses and the ineptness of the vaccination process (9 doses only per 100 people), one can reach the conclusion that Iraq would be able to vaccinate 70 percent of eligible persons no sooner than June 2024.

Vaccination began in Iraq in the ninth week of the year 2021. In the subsequent 12 weeks, vaccination rates and other indicators continued to fluctuate, rising at times and shrinking at others, which reflected a general uncertainty about vaccine feasibility, coupled with the strained influx of vaccines. As the 22nd week commenced, indicators began to rise, steadily and competitively, with the sourcing of larger quantities of vaccines into Iraq, which coincided with a string of unfortunate events: a series of fires in hospitals, increased fatalities among the younger groups, and growing outbreaks with the emergence of the Delta variant; all of which intensified the “epidemic panic”. Despite this, turnout rates continued to disappoint, as Iraq still has the highest COVID infection rates among the countries of the region. It has recorded 1,917,292 infections and 21,100 fatalities between February 24, 2020 and September 4, 2021. The Iraqi government plans on purchasing 48 million doses of vaccine, and expects some 20 million doses to arrive by the end of the current year, 2021.

Iraq has approved the use of four types of vaccines, three of which have been officially authorized and already administered. Those are: Pfizer/ BioNTech, Sinopharm, and AstraZeneca, while the Russian Sputnik V, though officially approved, has not yet been imported. Iraq has obtained its vaccines through political donations from China and the United States of America, before sealing direct purchase contracts with Beijing, or with the manufacturing companies through Washington and the World Health Organization, as part of the COVAX and Gavi initiatives in the early stages, after the vaccines had been licensed for global use.

The vaccines of political rivalry

It is noteworthy that Iraq's access to vaccines has been subject to the conditions of rivalry and polarization between international actors. The vaccine has become a tool for managing conflicts, used for gaining ground as well as enhancing influence and propaganda. China donated about 1,000 vaccine doses to the Iraqi political class in late 2020, 3 months before the vaccine was available to the general public. Beijing had utilized its Sinopharm vaccine as a valuable bribe that allows it to compete with the Americans in Baghdad.

Iraq has recorded the highest COVID infection rates among the countries of the region, with 1,917,292 infections and 21,100 fatalities between February 24, 2020 and September 4, 2021. The Iraqi government plans on purchasing 48 million doses of vaccine, and expects some 20 million doses to arrive by the end of 2021.

During the first vaccination campaign, which began on March 2, 2021, 50,000 Sinopharm doses granted by China were administered in Iraq, followed by an additional 200,000 free doses in April 2021. The Iraqi government had signed a contract with the Chinese government in September 2020 to purchase 8 million doses, hoping to receive the first shipment in early June, but the shipment arrived later, on August 13.

However, there were other – more serious - political repercussions for China's direct intervention in the epidemic situation in Iraq, as the country was offering its “valuable” aid in light of the rapprochements of the resigned government of Adel Abdul-Mahdi and the Iran-backed Chinese-Iraqi agreement. On the other hand, the United States was facing growing attacks in Iraq, pressuring the acceleration of its military withdrawal, with the end of the “rounds of strategic dialogue.” For the US, Vaccines were an ideal way to achieve a propagandist effect, presenting Washington as “the gentle hand that extends to help Iraqis overcome a stressful ordeal”.

Supplying urgent vaccine shipments to Iraq was linked to the sustainability of the relationship between the US government and an Iraqi government in accordance with it. As one of the outcomes of the “strategic dialogue” between the two countries, the US announced a donation of 500,000 Pfizer doses through the COVAX platform.

Russia, on the other hand, had been pressuring Baghdad to recognize its vaccine, even though it hasn’t donated any doses to Iraq, and neither has Iraq asked to import any. It is likely that the vaccine is thought to have high-risk side effects which discourage its importation.

Immune vaccines

The most serious consequence of the Chinese-American rivalry over influence in Iraq regarding the epidemic, was probably the imposition of urgent legislation to protect Pfizer company from possible prosecution should its vaccines cause any health ramifications to the vaccinated Iraqis. In fact, this was the company’s condition for it to agree to supply its vaccines to Iraq, whether through COVAX, US donations, or direct purchases by the Iraqi government. The Parliament subsequently urgently passed Law No.9 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic that includes provisions to provide statutory immunity for manufacturers, calling for an establishment of a national no fault compensation scheme. The law was passed just one week after the arrival of the Chinese donation.

Through the US government, Pfizer has pressured Al-Kazemi’s government, which – in turn - supported the company and drafted the law, making the company’s immunity effective under parliamentary legislation. Indeed, the parliament (with 193 out of 329 deputies present) passed a text to “protect vaccine manufacturers and their regional representatives from the demands resulting from combatting the pandemic.” The law, which can be called the “Pfizer Immunity Law,” included all other manufacturers of vaccines, even those who only asked for a promise to be exempted from prosecution, rather than a statutory law.

During the first vaccination campaign, starting March 2, 2021, 50,000 Sinopharm doses granted by China were administered in Iraq, followed by an additional 200,000 free doses in April 2021. The Iraqi government had signed a contract with the Chinese government in September 2020 to purchase 8 million doses, hoping to receive the first shipment in early June, but the shipment arrived on August 13.

Not only did the Parliament and the government grant early immunity to international vaccine manufacturers, but they also tried to make it difficult for Iraqi citizens to hold the Iraqi Ministry of Health accountable, under the pretext of “providing legal protection for the ministry and its employees”! Iraq still lacks a program to monitor the effectiveness of vaccines or apply clinical examinations, unlike Egypt, the UAE and Bahrain, which have taken part in China’s manufacturing tests, for instance.

Vaccination as a tool for surveillance

As the first shipments of the China-donated vaccines were arriving on March 2, 2021, Iraq launched a digital platform where people who wished to get the vaccine must register. However, the Ministry of Health made no effort to protect registrants' data, which is liberally shared with the National Security Directorate, and may be transferred to or used by other security agencies, as a government-owned database.

Moreover, the collection of this data may transcend its declared purposes to undeclared institutional uses, in a clear violation of privacy and medical confidentiality, crossing ethical redlines that regulate the limited circulation of personal data (1). The Iraqi Ministry of Health’s registration platform requires detailed information about residence, phone number, profession and location of work, and if the registrant is a government employee, they must specify the ministry or government authority with which they are affiliated. The registration also requires the disclosure of the national status by specifying whether the applicant is an Iraqi, a displaced Iraqi, or a foreigner.

The most serious consequence of the Chinese-American rivalry over influence in Iraq regarding the epidemic, was probably the imposition of urgent legislation to protect Pfizer from possible prosecution should its vaccines cause any health ramifications. In fact, this was the company’s condition for it to agree to supply its vaccines to Iraq, whether through COVAX, US donations, or direct purchases by the Iraqi government.

On the registration platform, all fields for data entry are fixed and mandatory, which means that applicants lose the right to voluntarily disclose their data, and are rather “coerced” to comply to predetermined steps. There are two mandatory requirements to ensure the correct completion of the application: First, one must verify the validity of the phone number by entering a code sent to that number into the relevant field on the platform, thus activating the second step, which requires the registrant to pledge “before the law” that the data provided is correct and that he or she is “aware that all rights are reserved by the Ministry of Health and in cooperation with the National Security Directorate.”

This final pledge is a sort of “threat,” that carries undertones of “physical disciplining,” and “the right to surveil” (2), which is what “obligatory vaccination” is, in practice. For example, full vaccination is a binding condition in order to practice one’s job, hold conferences and gatherings, enter government departments, obtain university student housing, and perhaps later, to participate in the elections.

The vaccine platforms in Iraq and Kurdistan have taken advantage of the times of crises in order to collect data, which could not have been possible otherwise. Those platforms do not apply the universal user data collection protocols, such as Usage Policy and Privacy Policy. Fear of privacy breaches stems from the fact that the regime in Iraq is fragile and untrustworthy, and therefore the transfer of power to extremist political groups is likely to occur in light of a precarious democracy, infested with corruption and the growth of militarism.

In any case, Iraq lacks a national framework for managing digital data collection and protection, and there is no legislation to regulate electronic activities. Instead, the judiciary relies on legal approaches drawn from the Penal Code of 1969, adapting provisions to the emerging “digital crimes.” The political system has been trying for several years to pass an unjust law that encourages restricting freedom of expression under the guise of “cyber-crime laws,” and there is no indication by which the legality of the state collecting digital data on its citizens is determined. The Constitution of 2005, established in the “digital age” also lacks references to the safeguarding of digital personal privacies, except for a broad reference in Article (17/First): “Every individual shall have the right to personal privacy so long as it does not contradict the rights of others and public morals.”

The vaccines of digital obedience

The measures taken by Muqtada al-Sadr in addressing his audience may be the most typical reflections of “surveillance” and “group disciplining” that lead to “political disciplining”, taking advantage of the pandemic - as its conditions allow the intervention in the lives of people, imposing patterns of leadership, direction and “obligatory subservience.”

Since the beginning of the pandemic, al-Sadr has been trying to take advantage of the crisis to test the extent of his influence within his broad group of followers, by measuring the extent of this group’s response to his instructions. His political exploitation of the epidemic went as far as measuring his popularity and people’s loyalty through a big project to collect digital data, dubbed “The Solid Structure”, in which his followers “voluntarily” disclose their personal information and data without knowing the purposes for which this data will eventually be used. Al-Sadr stipulated that all of his followers register on this digital platform, so that they are considered “true Sadrists” who support their reforming leader. Those who fail to comply would be expelled from the Sadrist Movement and rejected politically, organizationally, and perhaps even ideologically. At an early and undeclared stage of that same project, al-Sadr had ordered followers to adhere to social distancing and the use of sanitizers and masks, and at a later time, he declared that vaccination is a must. Non-compliers would be considered dissidents and, therefore, “deprived of his approval.”

Supplying urgent vaccine shipments to Iraq was linked to the sustainability of the relationship between the US government and an Iraqi government in accordance with it. As one of the outcomes of the “strategic dialogue” between the two countries, the US announced a donation of 500,000 Pfizer doses through the COVAX platform.

Al-Sadr’s instructions seem to be in line with the general universal recommendations, and sometimes, in favor of the recommendations of the official health authorities, but they also serve the purpose of reclaiming power over his own movement, which has been divided with the emergence of new centers of power that outdo al-Sadr’s influence; hence, his emphasis on the importance of vaccination. Al-Sadr even appeared in person to receive his vaccine shot before cameras, making him the only Iraqi politician to have received the shot in public, in an attempt to regain control of a dispersed power among internal rivals in the movement, while, at the same time, monitoring the number of his supporters who have answered the call of “digital obedience”, and observing the number of those who chose to ignore his command.

Vaccine discrimination

In large hospitals, people could usually get the most preferred type of vaccine, Pfizer/BioNTech, while AstraZeneca vaccines can be obtained from primary health centers in neighborhoods and regions. As for the Chinese vaccine, Sinopharm, it is circulated by mobile health teams in the various regions, markets and government departments to encourage people to take it, and since it can be transported easily due to the fact that its preservation does not require low temperatures.

The Ministry of Health made no efforts to protect registrants' data, which is liberally shared with the National Security Directorate, and it may be transferred to or used by other security agencies, as a government-owned database.

However, social skepticism remained a stubborn obstacle, discouraging healthy individuals from getting vaccinated, especially in light of hearsay misinformation, negative posts on social media platforms, and arbitrary warnings about the risks of vaccination by some religious figures. The failure to prevent religious congregations, in which millions of worshippers gathered, had further reinforced the skepticisms, amid rumors that performing these rituals would “give the believers immunity,” despite the fact that the prominent religious authority (Marji’), Ali al-Sistani, had issued several Fatwas on the “religious prohibition of violating health regulations,” declaring his support of “the prohibition of religious gatherings,” and asserting the “lack of conflict between Sharia laws and vaccination.”

The organizational inefficiency is also a reflection of conflicting practices, in light of the absence of a uniform national program for the distribution of vaccines. Instead of adhering to a single clear approach, the authorities have often resorted to improvised and propagandist solutions. For instance, in parallel with the official registration portal for vaccine seekers, the authorities also declared that those wishing to receive vaccination could just show up at vaccination centers, needless of a prior appointment, and regardless of priorities according to age or health, which created endless queues at vaccination centers and led to a shortage of doses in others. Afterwards, the health authorities launched mobile vaccination campaigns, and allowed specific parties to vaccinate their members exclusively (e.g. “Popular Mobilization Forces”). These patterns that governed the process of vaccination, along with the abundance of the vaccine in some regions and its scarcity in others, have all reinforced social aversion to vaccination and doubts about its feasibility.

The measures taken by Muqtada al-Sadr in addressing his audience may be the most typical reflections of “surveillance” and “group disciplining” that lead to “political disciplining”, taking advantage of the pandemic - as its conditions allow the intervention in the lives of people, imposing patterns of leadership and “obligatory obedience.” He has dubbed his project of data collection “The Solid Structure.”

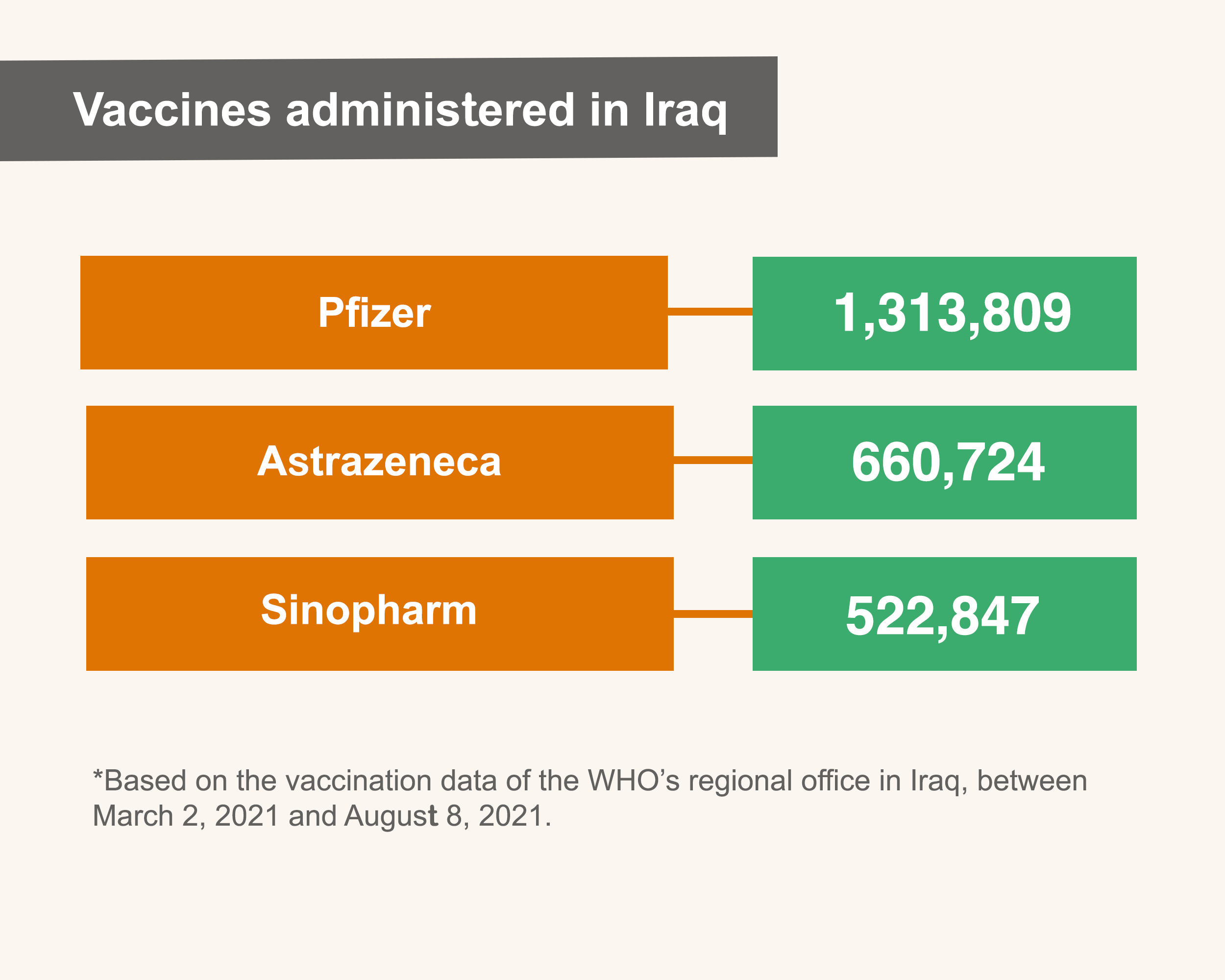

According to the data of the World Health Organization’s regional office in Iraq, 1,313,809 doses of Pfizer/BioNTech have been administered in the country, while the two other available vaccines have been less popular, with 660,724 AstraZeneca doses, and 522,847 Sinopharm doses administered during the period between March 2 and August 8, 2021. As a result, the Public Health Department had to increase the interval between the first and second Pfizer doses to 12 weeks to avoid shortages. The health authorities cannot prescribe specific vaccines to specific individuals, but it does encourage “compulsory vaccination”. The Ministry of Health explains: “We are keen to provide the citizens’ preferred vaccine type, in order to achieve the largest possible rate of vaccination.”

The problem with vaccination partly lies in the general mistrust in the state and its procedures. This has made “compulsory vaccination” a necessary step, which has inevitably lead to “coercive vaccination” for those whom the authorities are able to “physically discipline”, such as employees, subordinates and prisoners. Official institutions and local government bodies now impose compulsory vaccination, meaning that the priority to get the vaccine has been given to government bodies at the expense of the largest proportion of workers, wage-earners and employees of the private sector, in addition to the unemployed who face clear marginalization.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabah Jalloul

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 07/10/2021

1)- The National Democracy Institute (NDI), in its official guide for managing the respiratory pandemic (presented to governments and politicians around the world), recommends that surveillance programs or expansive use of new technologies to collect personal data and information on individuals, be open, transparent, limited, and subject to independent supervision, in order to prevent other government uses. For further information on the risks of digital data collection, see: The right to privacy in the digital age, a report by the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Index No. (A/HRC/39/29/3 August 2018).

2)- In his book “Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison” (1975), Michel Foucault considered that modern society uses the concept of “power-knowledge” in order to control. More knowledge leads to an authority that sits on top of an increasing level of surveillance. It shows the institution's ability to track and monitor individuals throughout their lives, while it spreads a persistent, tacit fear of it and a constant feeling of surveillance that infiltrates society.