This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Horrific scenarios and reality prevail in Yemen. An extremely impoverished Arab country with a Covid-19 outbreak, amidst a virtually complete collapse of the healthcare system, an ongoing armed conflict, and hundreds of deaths per day, possibly the aftermath of the pandemic, or not.

Prior to the official announcement of the Covid-19 outbreak in Yemen, WHO had estimated that half the population, of 30 million people, could catch the virus, and that nearly half a million people could die as a result.

During the last few years of Ali Abdullah Saleh’s rule, healthcare public spending made up 3-4 percent of the overall national budget. Most healthcare centres suffer lack of equipment, underfunding, understaffing in technicians and medical personnel, and limited reach of their healthcare services, especially in rural areas.

Poor response

No health guarantees are given to people infected with the virus, be it in terms of basic services or telling the truth in announcing the number of fatalities. A huge gap exists between the overall number of deaths and those whose cause is determined as Covid-19.

The impoverished country in the southern the Arab peninsula has paid an exorbitant price during the war that broke out in March 2015. The highest price, however, is still being paid today, as may be seen in the failed battle against the Covid-19 outbreak.

By April 7th, 2021, an estimated 5,233 people had caught the virus, of whom 1,022 died. (1) Lately, the numbers of infections in official government-controlled have been on the rise. The virus has been equally spreading in Houthi-controlled areas, home to the largest percentage of the population in the country, but also where the authority established there announces the numbers of neither infections nor deaths.

The death rate is quite remarkable when observed in light of the overall publicised number of Covid-19 cases. Until August 23rd, 2020, the number of confirmed cases reached 1,911, 553 of which ended in death. As such, the death rate makes up around 27 percent of all cases – that is, five times the global average. Yemen would thus be rendered home to the highest death rate in the world. Delayed testing may be the culprit behind such a gap, as patients suspected of carrying the virus are often tested only after the disease had reached an advanced stage. The actual number of infections, then, is many times more the declared one. As may be deduced from cemeteries, and the torrent of condolences running through social media, the number of deaths is quite massive.

However, with very few quarantine centres, poor healthcare services, and a shortage of tests, as well as people’s distrust in healthcare services, with plenty of rumours circulating around them, most people prefer to fight the disease in their homes, rather than be tested.

The collapse of the healthcare system and the Covid-19 straw

On April 10th, 2020, eve of the first discovered Covid-19 case, the healthcare system in Yemen had already “practically collapsed”, according to Jens Laerke’s description, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Human Affairs spokesman. According to a HeRAMS evaluation (2), 2477 healthcare facilities or 49 percent of 5,056 healthcare facilities all over the country are inoperative, or partially operational, due to damages, understaffing, shortage of medicine and medical supplies, or a limited access to facilities, a result of the security situation. Most hospitals in Yemen have no sanitary waste disposal systems.

Until April 26th, 2021, the overall number of confirmed cases reached 6,183, of which 1,205 were deaths, and 2,630 recoveries. It is interesting to note the death rate in light of the publicised number of cases, which means that the death rate makes up around 27 percent of all cases – that is, five times the global average, but it also means that the actual of cases is many times more the publicised one.

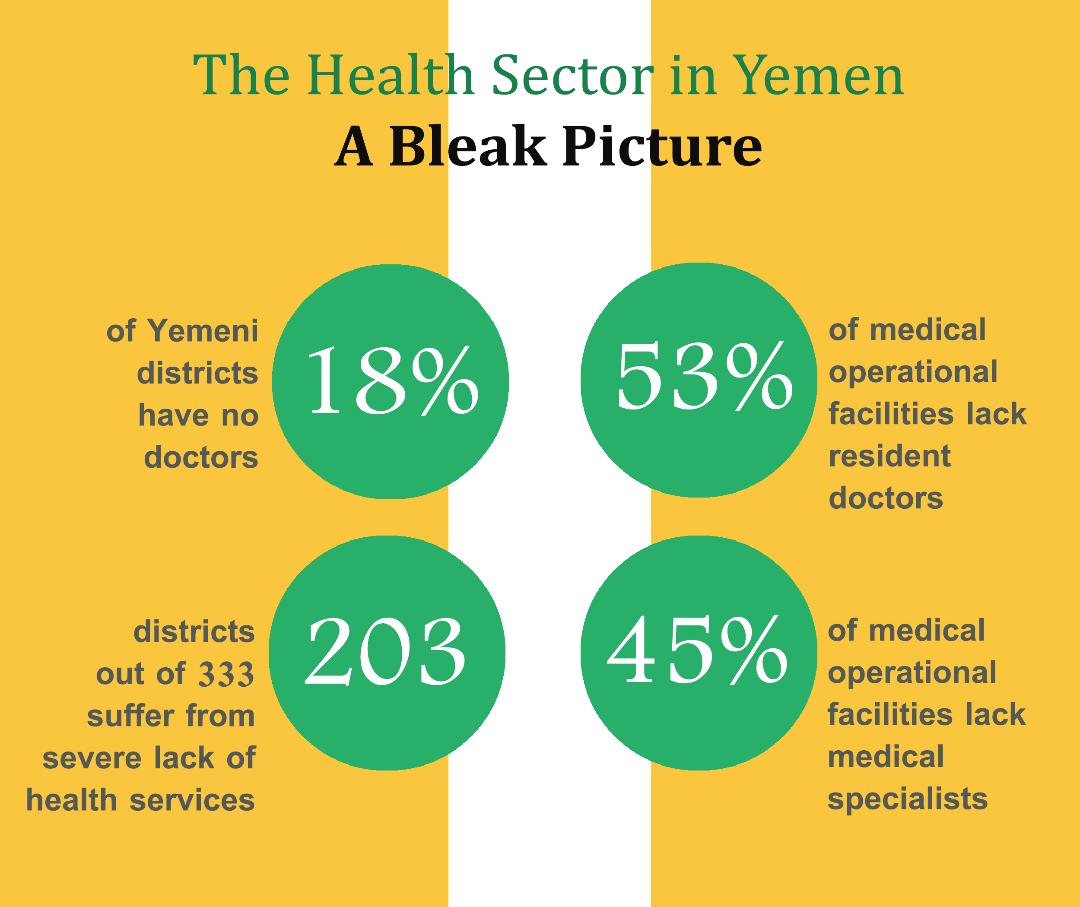

Two thirds of departments (203 out of 333 departments) are considered among the most in need of healthcare services, distributed across 22 governorates and with gaps in demand levels between one governorate and another. A number of healthcare workers were forced to relocate or leave their work for fear of attacks on healthcare facilities. Likewise, due to the checkpoints that different armed factions had set up, urgent medical supplies couldn’t reach the wounded or patients in hospitals.

Highly specialised medical personnel, like ICU specialists, psychiatrists, and foreign nursing staff have also left. According to a statement by a WHO representative in Yemen, since the beginning of the war, around 95 percent of foreign healthcare personnel have been removed, which weakened services in a number of hospitals. Only a few of them remained to fight amidst shortages of medication and essential medical supplies, recurrent power failures, and scarce fuel.

Ever since September 2016, the healthcare allocated budget dropped tremendously, which left healthcare facilities with no funding to cover operational expenses; likewise, healthcare workers’ salaries have been withheld. Healthcare workers’ wages in Houthi-controlled areas are still withheld today and, although maintained in the official government-controlled areas, have lost around three quarters of their value amidst a sharp drop in the Yemeni rial value.

An evaluation of healthcare needs as part of the general overview of humanitarian needs was carried out based on plan findings by the Health Resources and Services Availability Monitoring Systems (HeRAMS). There, 19.7 million people (out of the overall 30 million population) are estimated to require healthcare services and 14 million people to need those services. The rise in demand for healthcare services during the war years has resulted from an increase in the number of the war-wounded but also from the presence of a large number of displaced communities, of 3.34 million internally displaced refugees, among whom more than a million live within “dangerous conditions”. 270 thousand refugees and asylum seekers are there too, most of whom have hailed from the Horn of Africa. (3)

Many other extinct diseases and epidemics are now spreading. On November 2019, WHO stated that it had received more than 78 thousand reports from field monitoring teams in Yemen of 28 deadly epidemic diseases like “cholera, dengue fever, haemophilia, measles, pertussis, and polio.” (4) There’s also malnutrition, where around 15.9 million people (53 percent of the overall population) suffer from severe food insecurity, despite the existent humanitarian aid. Furthermore, malnutrition contributes to immunodeficiency.

Two thirds of departments (203 out of 333 departments) are considered among the most in need of healthcare services, distributed across 22 governorates. Doctors are lacking in 18 percent of the country’s department, while the majority of healthcare sector workers have not received their pay for the past two years.

Many clinics and hospitals now turn away patients, especially those have have Covid-like symptoms. Those hospitals justify such measures by saying that workers and doctors lack protective gear. Things got to a point where some hospitals had to close their doors for days – after some of their healthcare personnel had caught the virus – which was the case in the private Rawda Hospital in Taiz. People began to refuse going to hospitals for fear of catching the virus. (5)

For doctors in hospitals that have opened Covid-19 treatment centres, they fluctuated between having a combative spirit ready to fight the battle and concern over shortages of protective gear and fear of transmitting the virus to their families.

Generally speaking, Yemen suffers from a limited number of skilled healthcare workers. Furthermore, the country has been operating at half capacity in hospitals and healthcare centres, as healthcare workers are lacking in Yemen. Fifty-three percent of operational facilities have no resident doctors, and 45 percent lack specialists, with an estimated one healthcare worker per one thousand capita in Yemen.

Doctors are lacking in 18 percent of the country’s department, while the majority of healthcare sector workers have not received their pay for the past two years. Add to that an (already insufficient) number of nurses and midwives poorly educated and incapable of filling in for the deficiency in healthcare human resources. (6)

All this has ensued in the death of dozens of Yemini doctors. According to a statement issued on April 7th, 2020 by the Yemeni Doctors and Pharmacists Union, since the beginning of the outbreak, there have been 84 deaths among doctors and healthcare workers. Around 50 of those doctors had passed away during the first wave of Covid-19, which lasted from April to September 2020. It didn’t help Yemen that the virus had arrived three months late, nor that it had lost one whole year, even in terms of providing preventive supplies and protective gear for doctors and healthcare workers – who are at the frontlines of the pandemic.

Early failure

The Covid-19 Preparedness and Response Plan was launched in April 2020, right with the announcement of the first Covid-19 infection. As clarified in its definition, it is a “strategic document authored by Yemini authorities in Sanaa and Aden, with the support of WHO and other UN agencies, funds, programmes and healthcare workers in Yemen, with funder contribution.” The document included “the demands, needs, capacities, and measures that were determined by the authorities in Sanaa and Aden” and aimed at “ensuring Yamen’s capacity to detect, test, isolate, and treat any person susceptible of a novel coronavirus infection”.

The country has been operating at half capacity in hospitals and healthcare centres, as qualified healthcare workers are lacking in Yemen. Fifty-three percent of operational facilities have no resident doctors, while 45 percent lack specialists.

The document presented eight major axes of the national plan and said that it had relied on a regulated WHO methodology. Those are coordination, planning, and monitoring on a regional level, reporting risks and engaging society, observation and rapid response teams, checking cases, entry points, national laboratories, infection control and prevention (IPC), managing cases, and operational and logistic support.

The plan came as part of UN efforts towards a truce between the Houthis and the Internationally Recognised Government and the Arab Alliance. These efforts were fruitless, however. As the truce failed, efforts to unify the healthcare sector failed, along with coordinating response measures between Sanaa and Aden. Thus, each side was left to manage its own affairs in their control areas: the official government in Aden, the south, and Taiz and Marib governorates, and the Houthi government in Sanaa and the rest of the northern governorates under their control.

Crises, fighting, and epidemics on Yemen’s map

Until late May 2020, and at the peak of the pandemic, there was one centre in the provisional capital Aden designated to treat Covid-19 patients, where dozens of deaths were recorded every day. This was the only centre in the entire southern Yemen that served six governorates, besides Aden. The centre was established in the Amal Hospital through the support of Doctors Without Borders, as most private and public hospitals would turn away patients with Covid-19 symptoms. From April 30th to May 17th, 2020, this centre received 173 patients, of whom 68 died, the majority of whom are male and aged 40 to 60.

In Hadhramaut, the index of infections kept rising, pushing the local authority to set up al-Hayat Hospital as a self-funded quarantine centre. The centre comprised care rooms, sleeping beds, 6 x-ray machines, and 10 laboratory equipment.

Algeria: Healthcare in Times of Covid-19

06-06-2021

As for Taiz, to respond to the pandemic in areas that remained under the official government control, a sole quarantine centre was set up in the Republican Hospital, while relying on self-sufficiency and the support of organisations. Taiz is home to the biggest population among Yemen’s governorates (4 million people), with parts of it still under Houthi control. During the first wave, Taiz had but one treatment centre and thus failed to help Covid-19 patients, especially those who lived in rural areas. Being the only centre there, it remained crowded around the clock, and in bad shape. During the first wave of Covid-19, more than 25 people of medical personnel were infected.

In Marib, where fighting never stopped, the first confirmed case was documented on May 6th, 2020, while the measures taken to respond to the pandemic remained modest. Marib hospitals were still having trouble providing healthcare to the war casualties and patients with chronic diseases. The authorities in Marib adopted a few preventive measures, while public activity was suspended and a night curfew imposed. However, the risk remained bigger than containable. In Marib, there are 134 displaced persons camps from all over Yemen, some displaced by the war and who hailed from Africa as passage into Gulf countries, but remain stuck in Yemen. The UN High Commission for Refugees had warned that those were “most vulnerable to the coronavirus risk”.

Houthi denial

Before announcing the first case, the Houthi-led group had resorted to circulating a number of rumours, in an attempt to invest the virus in military propaganda. They accused the Arab Alliance of spreading the virus through their airplanes, blamed the humanitarian workers of spreading the virus, and imposed strict restrictions on humanitarian missions and their employees.

This did not stop the disease from spreading in Sanaa, and people began dying in large numbers without going to the hospitals. Businessmen established cemeteries at their own expense, ICU tariffs in private hospitals went up, and hospitalisation was accessible but for the rich.

According to a statement issued on April 7th, 2020 by the Yemeni Doctors and Pharmacists Union, since the beginning of the outbreak, there have been 84 deaths among doctors and healthcare workers. Around 50 of those doctors had passed away during the first wave of Covid-19, which lasted from April to September 2020.

However, authorities in Sanaa continued to hide facts and deny the existence of the virus, threatening doctors, hospitals, and journalists who said otherwise. Likewise, Houthis took, at gun point, those suspected of having caught Covid-19, and would not let their parents accompany them during their illness. They likewise banned dead people’s families from participating in funerals, in addition to keeping burial places a secret, without informing the families of the location of graves. The situation that the Houthis imposed resulted in rumours to the effect that patients were being killed in hospitals, through injecting them with what was locally termed as a “mercy injection”, which discouraged many patients from seeking healthcare in hospitals.

Still, there remained a small percentage of Covid-19 patients who received healthcare services in Sanaa and Northern Yemen, where the authorities in Sanaa designated the Kuwait Hospital to receive patients and suspected cases, but without officially announcing it, and amidst intensified measures, preventing doctors from going home for weeks, for example, among others. In mid-July 2020, Doctors without Borders said that it had started supporting a new Covid-19 treatment centre in the Sheikh Zayid hospital in Sanaa.

Doctors without Borders kept receiving patients with Covid-19 symptoms in all its healthcare facilities and supported them in Houthi-controlled areas in Hudaydah, Khimar, Hidan, Ibb, Hajjah, and Taiz… though without announcing the number of infections and deaths.

A small improvement then a fiercer wave

The situation improved a little in terms of Covid-19 treatment centres, whose number reached 24 (7), all of which are in official government-controlled areas. Quarantine centres are distributed over 13 Yemini governorates, but beyond Houthi controlled areas.

The second wave of Covid-19, however, looks much more aggressive, and Covid-19 centres in official government areas are barely enough to provide services to 5 percent of the population.

In southern governorates, entirely out of Houthi control, there are 16 quarantine centres, three of which are in the provisional capital Aden, two in Lahij governorate, and one sole quarantine centre in Dhale, like in Abyan. In Shabwah there are two centres, five in Hadhramaut, and in Mahra, in south-eastern Yemen, there is one quarantine centre, as well as in Socotra Archipelago in the Indian Ocean.

The rest of the centres are spread across the northern Yemini governorates, some which are out of Houthi control. In Marib there are three centres, and three others in Taiz, divided among various authorities. Al Bayda and Hudaydah, both under official, government control, have one centre in each.

Interestingly, most of these centres are located in central or smaller cities, while three quarters of Yemen’s population is still spread across rural areas – where ever the simplest services aren’t provided. Furthermore, accessing healthcare services amidst population fragmentation has become more difficult. In Yemen, there more than 130 thousand local communities, which hinders the creating a service structure that caters to the entire population. Things became further complicated in the shadow of the war, which rendered mobility difficult. Therefore, many rural areas suffered from the spread of the epidemic, with virtually nonexistent basic healthcare services.

Even with the option of accessing quarantine centres in cities, the equipment of these centres is simplistic, and ICU and hospital beds are always full. Due to the small number of factories, the majority of these centres have a problem providing enough oxygen, but also due to the lack of vision and coordination between healthcare institutions. The phenomenon of patients’ families buying oxygen in order to provide it to their sick relatives in their own homes has also spread.

The situation could’ve certainly been much worse, however, had centres like the Red Cross and Doctors Without Borders that provided healthcare services to Covid-19 patients not been run directly by the Red Cross and Doctors Without Borders. The rest of the population mainly depends on on international organisations’ aid, at the forefront of which is WHO.

Statistics as an indicator

Until April 26th, 2021, the overall number of confirmed cases reached 6,183, of which 1,205 swere deaths, and 2,630 recoveries (8). These statistics pertain to governorates under the control of the official, internationally recognised, government, as the Houthis, in control of northern Yemen, have only announced four Covid-19 cases since the outbreak of the pandemic. But even the numbers publicised by the official government of its areas are inaccurate, whereby they depend on statistics collected from quarantine centres only, while the number of deaths is many times more the publicised one.

Cemeteries and social media have thus become the real index of sizing the outbreak of the pandemic. The number of daily funerals has multiplied in cemeteries by ten, while the number of condolences on Facebook has reached a ratio of 7 out of 10 posts on the newsfeed.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 21/05/2021

1)According to the latest statistics carried out by the Supreme National Emergency Committee for Covid-19 in Yemen, set up by the Internationally Recognised government.

2)The Yemen National Covid-19 Preparedness and Response Plan is a strategic document authored by WHO, other UN agencies, funds, programmes, and partners operating in Yemen, and the contribution of funders. It was published on April 10th, 2020.

3)“The coronavirus implications in Yemen… war atop a war”, a research paper published on the Abaad studies and Research Center website on April 20th, 2020.

4)“The White Yemeni Army Has no Arms to Protect Itself”: a press report published don Free Media website.

5)“Covid-19 has destroyed anything left of the healthcare system in Yemen”: a report published on Doctors Without Borders website on June 10th, 2020. 2020.

6)“Health Workforce Requirements for University Health Coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals.”

7)Official Yemini Ministry of Health source who spoke with Assafir Al Arabi.

8)According to the Twitter account of the Supreme National Emergency Committee for Coronavirus.