This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Three Covid-19 deaths in a quarantine centre is nothing out of the ordinary. For a power failure to have caused them, however, reveals a total collapse of the health sector. Right around mid-April 2021, the capital of Sudan, Khartoum, witnessed exactly that. The minister of health announced the accident after the news had gone viral on social media, some contesting, some confirming it.

For months, Sudan has been facing severe power outages. The Sudanese Electric Distribution Company programmed the strictest power cuts in Sudanese history in decades, going as long as ten hours a day. Even though many health institutions resorted to private generators, a continuous electric current would sometimes be interrupted nonetheless – this time thanks to a fuel crisis bogging down Sudan. With power failures and temperatures rising up to 40 degrees Celsius, some bodies decomposed in Khartoum morgues.

The first wave: confusion

The first Covid-19 case hit Sudan in March 2020, launching the first wave that would last until August 2020. During that period, the healthcare system in Sudan was on the verge of a total collapse: the sector has been failing for a long while now, medical personnel were untrained and healthcare institutions unprepared to handle this new pandemic.

Worldwide response had its own issues to handle in its treatment of Covid-19, yet the situation in Sudan was quite particular – its healthcare crisis has been snowballing to a point where hospitals had neither oxygen nor surgical sutures, and a pregnant woman had to give birth in the middle of the road – as was documented in Khartoum media some seven years ago.

Throughout recent years, defence and security reigned supreme over state budget, amidst internal warring on more than two fronts. Their two budgets combined took over 50 percent of some of those state budgets, while the Ministry of Health received but a sliver: barely 1 to 3 percent. Scarcity or absence of healthcare services in governmental hospitals thus exacerbated and, subsequently, private investment in the health sector flourished, rendering medical services a luxury that the majority of the population could not enjoy.

With the first Covid-19 case, the spectre of death appeared before all Sudanese people. A few days later, then Sudanese Minister of Health, Akram Altoum, decided to close down all hospitals for fear of a viral outbreak, especially as medical personnel had neither response training nor medical supplies. That is, in addition to hospitals being unprepared to respond to this new epidemic. In parallel, such decisions have massively harmed people suffering from other diseases. And so, social media pages turned into a search engine to look for hospitals whose doors were still open to patients. Everyone asked and enquired about hospitals still receiving patients. It got to a point where some patients passed away on their journey in search of a hospital – that is, before hospitals reopened to resume their normal work. Otherwise, some hospitals made patients undergo Covid-19 tests as a condition to receiving them – tests with prices not all patients could afford. Likewise, patients with other diseases may have been harmed from hospital closures; however, according to a Ministry of Health official, the statistics are yet to be collected in that regard.

Dr Leila Hamad el-Nil, a Ministry of Health official and head of the emergency department, says that the ministry has introduced a plan that included all relevant actors and formed nine committees to manage the crisis. Sudan started off with 44 quarantine centres during the first wave, while today they might have reached around 80 in both Khartoum and the rest of the states. She continues, “Coverage in other states is reasonable, but pressure is high in Khartoum”, considering that the weight of the pandemic, along with healthcare services, problematic as they are, being all compacted in the capital. This chronic imbalance is the result of an extensive wave of migration from Sudanese states to Khartoum in search of essential services – with healthcare and education topping those rankings. A report by experts in local governance in 2011 noted that 13 states budgets relied on Khartoum, while Khartoum’s percentage of spending reached 78 percent of national income, 68 percent of which covers salaries and wages, while 4 percent of which covers developmental features. This clearly resulted in a scarcity of services or absence thereof. Some Sudanese states, like East and Central Darfur, lack every kind of specialised medical service, whereas many states lack mental health practitioners and neurologists, like Ash Shamaliyah, River Nile, Sennar, the Blue Nile, North Kordofan, and South Kordofan…

External aid: an attempt to save the saveable

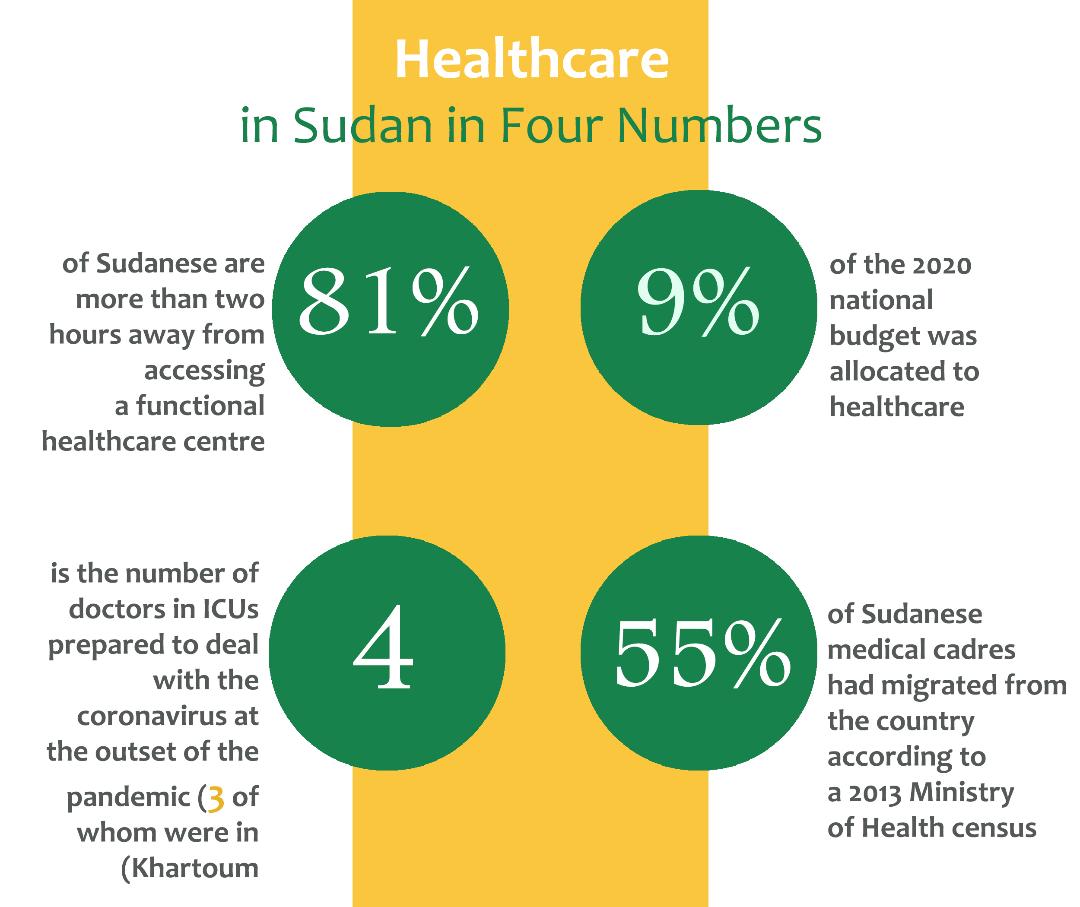

In Sudan, Covid-19 cases have exceeded 31 thousand infections and two thousand deaths. The pandemic affected all 18 Sudanese states, but Khartoum, Gezira, and El-Gadarif bore the biggest brunt of it. According to a WHO report that examined the health situation prior to the pandemic, around 81 percent of the population had no access to a functional health centre less than two hours from their homes. The decision to close down hospitals at the beginning of the first wave exacerbated the situation, of which WHO reported no more than 184 beds in ICUs, 160 of which have ventilators, with only four ICU doctors available – and ready to take in Covid-19 patients – three of whom were located in Khartoum and one in Gezira in central Sudan.

With the first case of Covid-19 in March 2020, the Sudanese Minister of Health closed down all hospitals for fear of a viral outbreak, especially as medical personnel had neither response training nor medical supplies. That is, in addition to hospitals being unprepared to respond to this new epidemic. Such decisions have massively harmed people suffering from other diseases, and turned social media pages into a search engine to look for hospitals whose doors were still open to patients.

Around 1,600 healthcare workers and rapid response teams received training. According to the 2019 annual statistics report (the latest) issued by the Health Observatory, the number of general practitioners in Sudan is 3,508, 1,180 of whom are based in Khartoum; the number of specialists is 1,941, 860 of whom are based in Khartoum; the number of hospitals in Sudan is 534. The report estimated a number of 32,745 beds all over Sudan, while, according the last census carried out by the Central Bureau of Statistics of 2008, Sudan has a population of 40,197,974.

A Ministry of Health official of the Sudanese response department says that some quarantine centres set up to fight the virus were constructed from nothing, while some had to be rehabilitated and fitted into quarantine centres. Notably, some quarantine centres had stopped operating, as they required water supply and electric rehabilitation. He also says that financial aid was mainly governmental at the beginning of the pandemic – more than 70 percent – that is, before international organisations intervened to respond to increasing case numbers and provided substantial aid. Sudan approved a 2020 budget with an overall deficit of 1.62 billion dollars, 9 percent of which the state allocated to healthcare, which equals 100 billion Sudanese pounds (SDG) (one USD equalled 50 SDG back then).

According to a performance report by the Ministry of Health, the latter asked the Ministry of Finance to approve 400 billion SDG to rehabilitate hospitals. The requested amount, however, never reached the Ministry of Health. It was thus forced to put an end to a number of its projects as a result of the pandemic, and reassigned some amounts budgeted to other special programmes to finance the Covid-19 crisis.

The Sudanese government is not inclined to provide information or numbers on funding and financial aid or detail how those are spent. Earlier, however, the ministry said its deficit had reached 70 percent of its budget. Some states supported Sudan in overcoming the Covid-19 crisis, like Turkey, the UAE, and Egypt, while the World Health Organisation announced that it would offer Sudan a million dollars in aid in late 2020. Likewise, according to an announcement made by the EU and the Ministry of Health, the European Union aided Sudan with 80 million euros in its response to Covid-19. In a report, the Ministry of Health noted that the EU aid programme was employed to maintain and rehabilitate 12 emergency rooms in different states, and train working personnel. Dr Leila Hamad el-Nil notes that some organisations were entirely responsible for running quarantine centres, even allocating worker salaries.

There are no more than 184 beds in ICUs, 160 of which have ventilators, with only four ICU doctors available – and ready to take in Covid-19 patients – three of whom are located in Khartoum and one in Gezira in central Sudan.

The trickiest challenge facing the Sudanese Ministry of Health is handling cases, including equipping centres to receive all cases, as well as provide oxygen and transport it to states. Since the beginning of the pandemic, Sudan has suffered a severe oxygen crisis; oxygen factories had stopped working, either due to deterioration that affected the entire health sector, or due to halted activity in many production sectors in Sudan – as part of the economic regression and collapse of the national currency. Right now, eight oxygen factories are operational in Sudan, while some states have resorted to establishing their own factories in an attempt to avoid transportation, shipment, and useless administrative hurdles that have previously hindered punctual delivery of aid supplies. Those are the very same issues that resulted in shortage of work supplies in some regions of Sudan, like protective gear and others. According to the Ministry of Health, the first wave had caused complete confusion, intertwined with failure and miscalculations. During that wave, however, Sudan started off with a relatively reasonable response, despite limited capacities, infrastructure deterioration, or lack thereof in some areas. The ministry followed a response plan, which it would update every six months, where it tackled the need for training, provisions supply, monitoring and coordinating committee operations, determining types of required tests, as well as its routine administration of health institutions. Ministry of Health reports note more than ten diseases for which patients frequented hospitals, most prominent of which are malaria, followed by pneumonia, diarrhoea, and respiratory and hypertension diseases.

Number of cases grows, affirmed numbers are questioned

Covid-19 deaths in Sudan have passed the two thousand mark. A report issued by Imperial College London, however, mentioned a much higher number of infections and deaths than announced. It stated that the current number of announced deaths in Sudan represents but two percent of the actual number – that it was lower by 16,090 deaths than the real number. The British report estimated around 38 percent of Khartoum residents to have caught the virus, with a population, according to the most recent census conducted by the Central Bureau of Statistics, of around eight million people – though other estimates have noted that the capital was home to a population larger than ten million people. International organisations warned of potential collapse to the health system in Sudan in the shadow of the coronavirus pandemic.

Sudan has suffered severe shortage of medical supplies, which began with the 2011 separation of South Sudan and, consequently, the extraction of oil revenues from its state budget. In the aftermath of scarce foreign funding, more than ten international companies stopped working. The crisis aggravated all the way to the collapsed local currency and exacerbated inflation, which jumped to 330.78 percent in February 2021. The debt burden of the medical supplies institution (the governmental department in charge of medical imports) reached 70 million euros, which the Ministry of Finance failed to repay, resulting in pharmaceutical losses. Pharmacists led a movement of uninterrupted protest, going on strikes every once in a while, in an attempt to pressure the government to provide medicine.

Health insurance coverage: heath cards to no avail

Though a governmental public service, health insurance does not cover citizens’ medical needs and treatment; especially with the decline, and sometimes absence, of services of governmental facilities, particularly in the states, and the expansion of private investment at the expense of public health. According to the 2019 annual performance chart of Khartoum’s health insurance company, public health insurance in the state of Khartoum covers more than a million households, at 84 percent. The number of hospitals covered by the insurance network is around 400, while the number of medical service facilities is 308. As regards health insurance services to the rest of Sudan’s states, they covered more than 80 percent of the insured. That network comprised more than three thousand hospitals and around 2,700 pharmacies. At first glance, it could appear that the insurance service provided by the state is reasonable when considering the size of the population. However, reality is quite divorced from those numbers. Every citizen with a health insurance card is not necessarily guaranteed medical services and treatment as required, be it for free or for a small sum. Rather, such a card is rendered meaningless in the shadow of an exhausted healthcare system, incapable of sustaining itself, its citizens carriers of a card that offers zero services. Even private medical insurance, a service extended by private companies to their employees, has also sometimes proven to be useless, as quality medical services would become exclusively accessible in private sector hospitals. Insured citizens have been witnessing a substantial exodus of larger hospitals from the network of public coverage – as a result of debt accumulation or delayed debt repayment, accompanied by an increase in medical and medicinal costs.

Private hospitals neither heeded nor engaged with the question of the Covid-19 outbreak. All quarantine centres remained in the custody of the Ministry of Health.

Sudan started off with 44 quarantine centres during the first wave, while today they have reached around 80 in both Khartoum and the rest of the states. Healthcare services, problematic as they are, are all compacted in the capital. This chronic imbalance is the result of an extensive wave of migration from Sudanese states to Khartoum in search of essential services – with healthcare and education topping those rankings.

The transitional government of Sudan inherited a precarious health system from Al-Bashir’s overthrown government in April 2019 – that is, in addition to corruption that infiltrated all state apparatuses. As healthcare shares were at the bottom of state interests all throughout Al-Bashir’s rule, the health sector could now use some quality support that potentiates its resurrection from its current state and, subsequently, its provision of reasonable medical services – from training staff all the way to, but not stopping at, easily finding and dispensing prescribed medications. Amidst this situation, and following South Sudan’s separation and economic collapse, the migration of medical personnel abroad has remarkably accelerated.

In 2013, the Ministry of Health announced that 55 percent of medical personnel have immigrated and announced its need for more than 60 thousand medical personnel. Doctors in Sudan suffer low wages and unfit work environments; they are also often victims of assault by companions to patients, who protest against poor hospital service or lack thereof.

During the past few years, demand for seeking treatment abroad has been on the rise, driven by the decline of healthcare services – whether pertaining to diagnosis or availability of treatment.

Following the separation of South Sudan and economic collapse, medical personnel increasingly and noticeably left the country. In 2013, the Ministry of Health reported that 55 percent of medical personnel have immigrated abroad.

According to the 2019 “Medical Qoumassioun”, 2019 spending on medical treatment abroad reached more than 57.826 million dollars, in comparison with 2018, where it was around 22.613 million dollars. This amount includes only those referred for treatment abroad through the “Qoumassioun” – a governmental system in charge of covering some treatment costs. Additionally, patients’ financial procedures are charged in official USD exchange rates, which is worlds away from the black-market exchange rate, no longer so, though, after the recent announcement of the liberalisation of the Sudanese pound.

***

Sudan is considered one of the countries with a limited Covid-19 outbreak. It is widely held that African countries, which enjoy a warmer or hot weather, have recorded the smallest number of Covid-19 cases – unlike Europe, for instance. Despite Sudan figuring among such countries, the death-to-infection rate is considered appalling. Despite Ministry of Health awareness-raising programmes, but especially as no Covid-19 cure has been found, the Sudanese, when feeling Covid-19 symptoms, are unlikely to seek treatment in hospitals and prefer to seek antibiotic treatment directly through pharmacies or resort to herbs altogether. It is therefore believed that the number of infections that did not reach the Ministry of Health or went unreported through the Ministry of Health are much bigger than the official number. Just like their compatriots of the MENA region, the Sudanese approach the coronavirus lightly, even cynically, considering it a “premeditated” political measure, which the crises-ridden provisional government adopted in order to close down the country and, therefore, lower pressure on demand for commodities and scarce, or sometimes absent, services. On the other hand, the Sudanese, like the rest of Africans, are generally convinced that they enjoy a very high genetically-evolved immunity to diseases, keeping the damned malaria in mind, whose reach has finally begun to wane, but only after reaping thousands of lives over many years.

The Sudanese do not view the Covid-19 pandemic as having aggravated the health situation: a collapsed health sector is the general state of affairs in Sudan. Rather, they perceive this new pandemic as an obstruction to life and production – however scarce it had been beforehand. With the first wave, the authorities immediately enforced a sanitary state of emergency; the capital, Khartoum, was locked down for around six months, airport movement and land crossings were blocked and a curfew that allowed the people a few hours of shopping was imposed – as big stores closed their doors. No official numbers exist to indicate the extent of losses and repercussions Covid-19 had on the economy. Still, economists estimate a million dollars a day in losses, while the Exports Chamber estimated that overall cattle exports to Saudi Arabia were affected by nearly 60 percent. The Federation of the Chamber of Small and Handicrafts Industries, and which comprises 32 professions and trades, announced that the living standards of two million of its working members have been harmed by the imposed sanitary lockdown.

Just like their compatriots of the MENA region, the Sudanese approach the coronavirus lightly, even cynically, considering it a “premeditated” political measure, which the crises-ridden provisional government adopted in order to close down the country and, therefore, lower pressure on demand for commodities and scarce, or sometimes absent, services.

And the pandemic’s biggest winner? Traders! The prices of commodities doubled with the beginning of the lockdown and the enforced curfew, which exacerbated citizens’ economic conditions. On the other hand, security and military affiliates found an opportunity to forge and sell curfew passes, which the authorities reserved to medical personnel and security forces at the beginning of the wave. Obtaining a curfew pass thus no longer required medical or military cards, but rather just access to money. Such prohibitions doubled Sudanese suffering, an estimated high percentage of whom are day labourers. All the while, schools and universities were suspended, as governments failed to meet lockdown measures with distance learning: pupils and college students thus lost one entire year.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 25/04/2021