This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

To turn the Rafik Hariri University Hospital, and its faded blue, from a neglected governmental hospital, afflicted with material and logistical crises, deficient maintenance, and employees in a continuous struggle to obtain their rights and salaries, into that pioneering hospital at the forefront of the fight against the coronavirus pandemic in Lebanon encapsulates the problematic nature of the public healthcare system in Lebanon.

With the exception of a few accomplishments from early post-independence Lebanon, some of which are essentially vestiges of the French mandate or realised during Fouad Chehab’s presidency –which stood out for establishing public institutions (1958-1964)– the Lebanese state has failed to support public sector hospitals. Since the end of the civil war (1975-1990), there has been no investment in advancing governmental hospitals; in parallel, governmental hospitals have failed to gain society’s trust, that is, in the shadow of an already strong private hospital sector, which, in turn, never stopped growing - or ransacking Lebanese pockets for that matter. Lebanese citizens have yet to get used to the idea that they could receive proper, quick, and effective treatment at a governmental hospital without recourse to cash payments or a long wait, or possibly death, by hospital entrances. The concept of free and advanced public hospitals, namely, the right to free healthcare, was (and still is) a virtual fantasy for Lebanese citizens rather than a basic human right.

Still, with the first Covid-19 case confirmed in February 2020 in Lebanon, the start of the global outbreak, and in the shadow of fear and anxiety that the new unchartered virus created, hasty and often inept preventive and protective measures, and sights of panic, empty streets, worldwide airport closures, the Rafik Hariri University Hospital dusted itself off and became the frontline hospital, the backbone of combatting the pandemic. Similarly, as private hospitals in the capital and periphery shirked their responsibilities, other governmental hospitals in different Lebanese cities, each with its own capacity and equipment –and despite a neglected periphery amidst a clearly centralised hospital mapping– stepped up and self-organised to receive and monitor patients. Those are the very private hospitals that have been singing and propagandising for decades for their image as “Hospital of the East”, as ensuring their patients care, health, and wellbeing, as cutting-edge with their equipment and visionary endeavours and at one with progress.

Lebanon: A Special Type of Rent

13-12-2020

It’s as if the coronavirus pandemic presented the public health sector a chance to “retaliate” against the private sector, an opportunity to “reposition” itself and prove that the public health sector could be the sanitary authority and backbone of society. It presented an opportunity to “oxygenate” citizens, both literally and metaphorically, and emphasised the importance and emphasised the importance of reevaluating and altering health policies, consolidating and developing the public health sector, and guaranteeing everyone the right to health.

Once at this hospital…

Many years ago, I underwent surgery at the Rafik Hariri University Hospital, a governmental hospital and the only hospital that would receive me without any health insurance coverage. As I sat in the hospital bed, a friend called to check up on me and teased: “And so you ended up at the Hariri Hospital of all places!” My surgical operation and cuts are long gone and mended, but that sarcastic remark has remained dormant, until awakened by the ongoing response to the pandemic in Lebanon.

Since the end of the civil war (1975-1990), there has been no investment in advancing governmental hospitals; in parallel, governmental hospitals have failed to gain society’s trust, that is, in the shadow of an already strong private hospital sector, which, in turn, never stopped growing - or ransacking Lebanese pockets for that matter. Lebanese citizens have yet to get used to the idea that they could receive proper, quick, and effective treatment at a governmental hospital.

It’s as if the coronavirus pandemic presented the public health sector a chance to “retaliate” against the private sector, an opportunity to “reposition” itself and prove that the public health sector could be the sanitary authority and backbone of society. It presented an opportunity to “oxygenate” citizens, both literally and metaphorically, and emphasised the importance of reevaluating and altering health policies, consolidating and developing the public health sector, and guaranteeing everyone the right to health.

On February 21st, 2020, the Lebanese minister of public health announced the first confirmed case of the novel coronavirus in Lebanon – a woman that had arrived by plane from Iran, and that there were two suspected cases that were quarantining at the Rafik Hariri University Hospital, where their health condition was being monitored around the clock.

Within 72 hours, and to mitigate the risk of infection, it was determined to set up a Covid-19 hospital, isolated from the rest of the hospital wards, with its own separate corridors and medical staff.

What a change! From governmental policies and civil imagination virtually devoid of free public hospitals, from deliberate disregard for governmental hospitals and their public sector – and in the shadow of small and limited budgets, political, sectarian, and opportunist favouritism that spare no governmental institutions in sectors like health, education, infrastructure, and others – to a novel and unique experience in this country.

Accredited by the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) and the World Health Organisation (WHO), considered to be the main authority on disaster management, the Rafik Hariri University Hospital holds 433 beds and 14 operation rooms; its Emergency Management Unit and the Epidemiology and Infectious Diseases Division had been set up on hospital site to tackle epidemics, natural disasters, and wars (prior to Covid-19. Furthermore, this hospital quickly turned into the main reference Syrian refugees sought for medical treatment; notably, the number of Syrian refugees in Lebanon exceeds one and a half million, whereas the entire country population is short of four million people.

Within 72 hours, and to mitigate the risk of infection, it was determined to set up a Covid-19 hospital, isolated from the rest of the hospital wards, with its own separate corridors and medical staff.

With the first coronavirus case confirmed, all hospital divisions got equipped medically, technically, and architecturally. In cooperation with the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the department of engineering and maintenance would carry out more than 30 projects to rehabilitate the hospital, while 14 teams monitored engineering and civil affairs, ensuring power, connections, telephone, and internet services were in supply. Those teams managed to isolate the hospital from the private ward through a number of different mechanisms, including separate elevators that stopped only at Covid-designated floors. Covid-only washing machines were brought in, and 80 CCTVs were installed in rooms. The medical and technical team thus managed to equip four wards designated to receive Covid-19 patients, containing 80 beds and 25 ICU beds, upgraded the maternity ward to receive pregnant women with Covid-19, and four new neonatal ICU beds. They also equipped rooms to accommodate dialysis patients with Covid-19.

In no more than 24 hours, a special emergency room, four surgical negative pressure rooms, and a room for ICU monitoring were set up, that is along with a separate four-floor building that holds 50 beds to accommodate and house on-call nurses and doctors.

The Covid-19 emergency ward thus constitutes a micro hospital that had been previously refurbished through an ICRC and Avina Foundation (a charity foundation in Latin America) donation, now set up to respond to the coronavirus.

The hospital management handled training healthcare workers to wear protective suits, interdivision coordination, and drafting special protocols as approved by the infection prevention and control department, including, for instance, the medical waste ridden with the virus.

Since February 10th, 2020 and even before the first coronavirus case was confirmed, the medical laboratory had been equipped and prepared, and so became the first in Lebanon to handle Covid-19 testing, requesting its detection kits from WHO. The lab helps provide epidemiological surveillance campaigns and test patients received at the emergency room. It also distributes External Quality Control tests to all MOPH licensed coronavirus laboratories in Lebanon.

The hospital allocated material sums to purchase protective gear for medical staff and healthcare workers, from protective suits to disinfectants, as 150 litres of hand sanitisers are required on a daily basis; as such, based on WHO recommendations, the hospital pharmaceutical department fabricated and distributed those disinfectants to hospital departments.

As such, the number of governmental hospitals designated to control the coronavirus in both Stage 1 and 2 is 12, the number of beds for stage 1 was 343 beds including 59 ICU beds and 57 ventilators, while the number of beds during Stage 2 reached 1197 beds. And now (April 2021), the number of coronavirus beds has reached 2,217, while coronavirus ICU beds counts 1,176.

The hospital opened its door for volunteering in its nursing and pharmaceutical departments and received aid from international actors and organisations, including WHO, ICRC, and the HRC, and welcomed material and monetary donations.

In April 2020, an emergency response centre was launched with the support of MOPH, Ministry of Communications, and the OGERO Company. It sought an increase in capacity to receive calls and to assemble a database that provided indexes essential to health conditions. This centre no longer works today, however.

The governmental Rafik Hariri University Hospital constituted a pioneering and daring experience in the potential of investment and trust in the public sector. While it faced many difficulties, including occasional irregular supplies of mazut fuel and shortages in medical supplies and protective gear, its medical staff and nurses stepped up to the challenge of fear and separation from their families and showed a clear commitment to serve and save patients’ lives. The latter are mainly made up of gradates of the Lebanese University, yet another governmental and free university, just as often neglected and questioned by the authorities.

On February 14th, 2021, the national Covid-19 vaccination campaign was launched from this hospital, whose ICU head received the first vaccine in Lebanon. Based on its daily report (of April 12th, 2021), this hospital is currently treating 111 covid-19 patients, including 52 critical cases, and the total number of recovered cases since the beginning of the crisis and until that date amounts to 1091. In addition, the vaccination communications centre helps citizens to fill out a registration form and follow up on it, as well as monitors vaccinated citizens.

Regional Preparedness and Response Plan for COVID-19

On March 10th, 2020, the Regional Preparedness and Response Plan for COVID-19 was introduced, in line with WHO recommendations. Stage 3 of the plan, that is, epidemic containment, included monitoring land, maritime, and air border crossings, banning travel to endemic areas, testing every suspected case in one sole lab – at the Rafik Hariri University Hospital – and quarantining all confirmed positive cases…

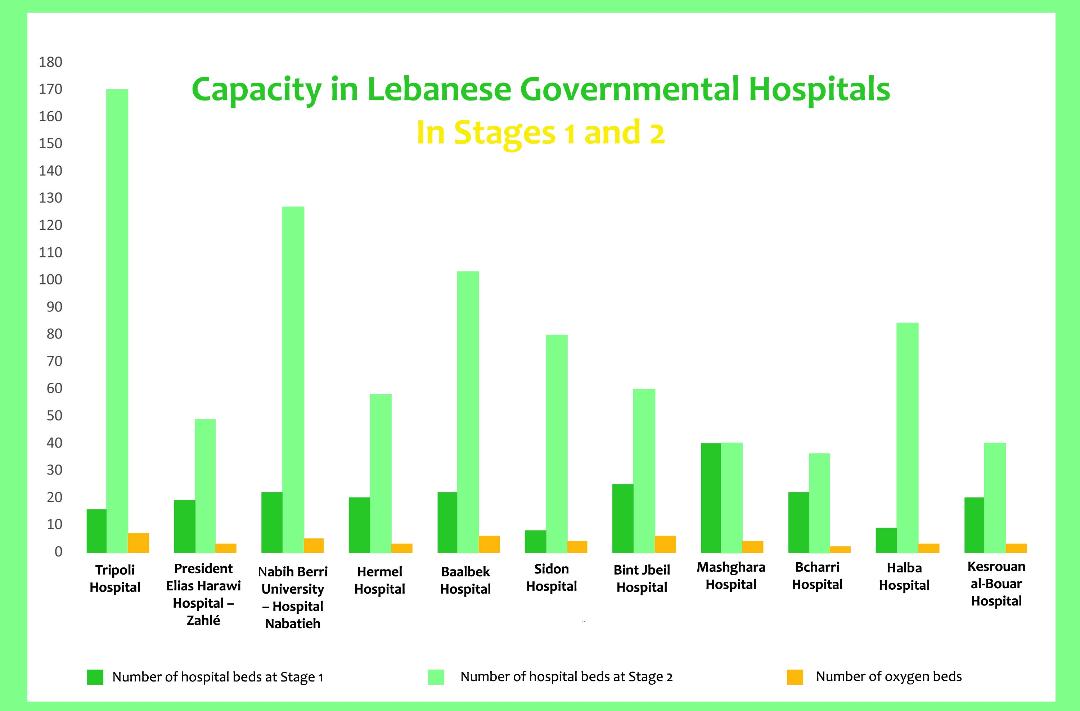

As for the hospital sector, Stage 1 focused on designating 11 governmental hospitals, in addition to Rafik Hariri University Hospital, to receive coronavirus cases, to be joined by other hospitals during Stage 2, while giving private hospitals the time to organise themselves in preparation.

Governmental hospital readiness in both Stage 1 and Stage 2 looked as follows:

Tripoli Central Hospital: number of hospital beds for stage 1 (16), total number of beds for stage 2 (170), number of ventilators (7)

President Elias Harawi Hospital – Zahlé: number of hospital beds for stage 1 (19), total number of beds for stage 2 (49), number of ventilators (3)

Nabih Berri University Hospital – Nabatieh: number of hospital beds for stage 1 (22), total number of beds for stage 2 (127), number of ventilators (5)

El Hermel Hospital: number of hospital beds for stage 1 (20), total number of beds for stage 2 (58), number of ventilators (3)

Baalbek Hospital: number of hospital beds for stage 1 (22), total number of beds for stage 2 (103), number of ventilators (6)

Sidon Hospital: number of hospital beds for stage 1 (8), total number of beds for stage 2 (80), number of ventilators (4)

Bint Jbeil Hospital: number of hospital beds for stage 1 (25), total number of beds for stage 2 (60), number of ventilators (6)

Mashghara Hospital: number of hospital beds for stage 1 (40), total number of beds for stage 2 (40), number of ventilators (4)

Bcharri Hospital: number of hospital beds for stage 1 (22), total number of beds for stage 2 (36), number of ventilators (2)

Halba Hospital: number of hospital beds for stage 1 (9), total number of beds for stage 2 (84), number of ventilators (3)

The Kesrouan al-Bouar Hospital: number of hospital beds for stage 1 (20), total number of beds for stage 2 (40), number of ventilators (3)

As such, the number of governmental hospitals designated to control the coronavirus in both Stage 1 and 2 is 12, the number of beds for stage 1 was 343 beds including 59 ICU beds and 57 ventilators, while the number of beds during Stage 2 reached 1197 beds.

The hospital plan reveals how centralised Beirut is at the expense of other cities. For example, Elias Harawi Hospital in Zahlé needed rehabilitation in order to receive cases that didn’t require intensive care and technical reasons were behind its limited its capacity to offer proper isolation. Other hospitals like Sidon, Hermel, and Ftouh Kesrouan-Bouar hospitals needed a week to prepare, while three governmental hospitals had been already closed down and unfunctional.

Hospital funding mainly relied on a loan from the World Bank, the HRC, some UNISEF credit, and ministry and hospitals budgets. Committees were thus formed to determine medical needs and prepare hospitals, ventilators, and PCR tests.

Private hospitals were alerted to be completely prepared once governmental hospital capacity was exceeded. Those are private hospitals of tier one, categorised T1, counting 53 hospitals and spread all throughout Lebanon. During Stage 1, private hospitals had 230 beds 65 ventilators for children and 220 for adults.

The information processing system was likewise upgraded to collect databases from different hospitals that worked to diagnose and treat coronavirus cases as well as set up a schedule to periodically collect nationwide information on available medical equipment, healthcare workers, and others.

Scientific evaluation of the national response plan: lack of policies

The report the Knowledge to Policy Center -K2P (1) at AUB issued in March 2020 noted that, in relation to the so-called “rapid response” outlined in the Regional Preparedness and Response Plan for COVID-19, the measures were rather reactive than proactive as many public and private hospitals were unprepared and ill-equipped. It also remarked on the limited coordination between health-related sectors, lack of a clear plan that addressed society’s most vulnerable, like refugees and prisoners, and failure to provide financial and social assistance to affected sectors or psychological support where needed.

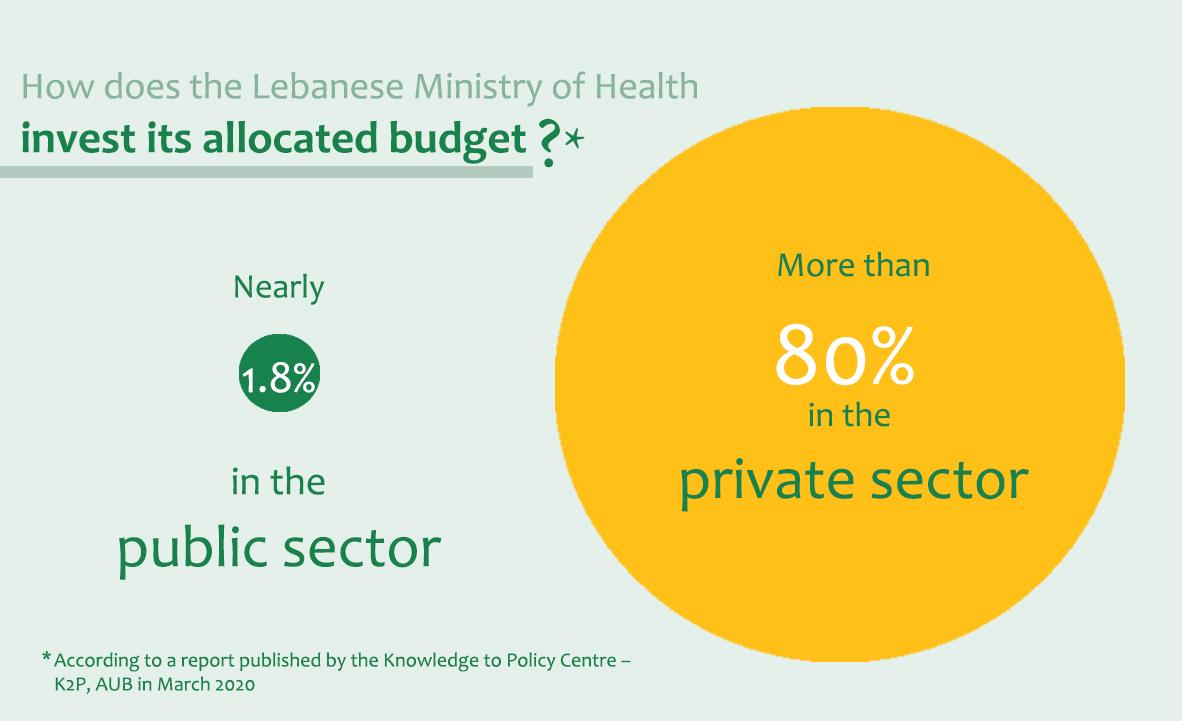

Only 1.8 percent of MOPH is invested in public hospitals, while more than 80 percent is invested in private hospitals and medication. Likewise, 15 percent of hospital beds belong to the public sector as opposed to 85 percent to its private counterpart.

The report noted many challenges that face the Lebanese healthcare system that impede viral containment, including the incompetent public health system, which relies on a cure approach rather than a preventative one (barely 5 percent of MOPH budget is allocated to primary healthcare), and which has received limited support, if at all, ever since the end of the civil war – for political reasons, conflicts, and sectarian contention. It is underfunded, understaffed, and ill-equipped. Only 1.8 percent of MOPH is invested in public hospitals, while more than 80 percent is invested in private hospitals and medication. Likewise, 15 percent of hospital beds belong to the public sector as opposed to 85 percent to its private counterpart.

At the beginning of the crisis, private hospitals did not partake in the management of the novel coronavirus outbreak, due to rising treatment costs and lack of a clear enforcement of the 1957 infectious diseases law on inter-sector coordination and the responsibilities the authority bears towards them. It weakened their capacity to run tests and speedily monitor suspected cases during the early stages of infection, added to the lack of a clear action plan of private-public hospital coordination, including already limited medical and logistic capacities, essential medical supplies and equipment, ICU beds, and ventilators – already insufficient in case of a viral breakout.

In their evaluation of the national plan, centre researchers who wrote the report noted lack of a solid health information system in Lebanon, that it was noncomprehensive and inconsistent, with limited ability to collect, analyse, or process sanitary databases to help make effective and conclusive decisions on the pandemic outbreak.

The K2P at AUB issued a report that evaluated the national plan and noted weak, noncomprehensive, and inconsistent health information system in Lebanon, with limited ability to collect, analyse, or process sanitary databases to help make effective and conclusive decisions on the pandemic outbreak.

Until April 12th, 2021 and since the beginning of the outbreak, the Lebanese MOPH had reported 497,854 confirmed cases, 6,703 deaths, and 408,659 recoveries. 2670 confirmed cases were also reported among healthcare workers.

Director of the K2P Center at the AUB, Fadi El-Jardali (2) remarks that the coronavirus pandemic exposed the flawed decision the Lebanese state had made decades ago: not to invest in public sector hospitals, to the benefit of decisionmakers’ interests. With the beginning of the spread of the pandemic, private hospitals shirked their responsibilities and were ill-equipped. Public institutions were incapable of rising to the challenge alone; resources were insufficient, and public-private coordination lacking. The response plan was ill-timed and too late. The coronavirus equally revealed social injustices in healthcare and social service provision, and in ensuring a just and inclusive access to healthcare.

El-Jardali adds that public hospitals constituted the frontline in responding to the crisis and supporting the population. The governmental Rafik Hariri University Hospital thus shaped a new and bold experience, a reference to be extended to the rest of public hospitals in future consolidation of public hospital systems and their capacities.

According to the director of the centre, the coronavirus outbreak revealed a stark inexperience in public health in the region. On the other hand, in countries where experience was available, governments failed to tap into it in response to the crisis, rather prioritising political and economic considerations over sanitary guidelines. The case of Lebanon thus shows failure to coordinate policymaking as the advice of public health experts was ignored – though supported by evidence. Furthermore, even when some committees did include public health experts, they lacked executive authority. El-Jardali stresses that the coronavirus constituted a public health lesson to the entire world, revealing the impact of proper and effective investment in public health as intertwines with political, social and economic determinants.

Current reality in Lebanon

Until April 12th, 2021 and since the beginning of the outbreak, the Lebanese MOPH had reported 497,854 confirmed cases, 6,703 deaths, and 408,659 recoveries. 2670 confirmed cases were also reported among healthcare workers.

Until April 11th, 2021, the number of coronavirus designated hospital beds had reached 2,217, while coronavirus ICU beds counted 1,176. WHO data shows that five hospitals in Lebanon participated in the WHO-led clinical trials, feeding their results into the global database to inform effective Covid-19 treatment.

According to WHO, the cumulative number of tests carried out since April 10th, 2020 has reached 3,629,646, and by April 12th, 2021 the number of people registered for the vaccine shot had reached 1,145,451, while 285,203 vaccine shots have been distributed, with 53.12 percent female and 46.88 percent male.

The last report, which IHME issued on April 8th, 2021 notes that the number of coronavirus infections and deaths in Lebanon has been declining, but that the situation is still critical, especially with the spread of the British variant. The report database foresees 3,000 new coronavirus-inflected deaths in Lebanon between April and the upcoming August.

The numbers also show that the average coronavirus death rate in Lebanon surpasses four out of one million, and thus constitutes the number-one reason of death in Lebanon these days. It is estimated that 26 percent of the Lebanese people have caught the virus, 71 percent of Lebanese citizens wear masks when leaving their house, and 78 percent of citizens have agreed to take the vaccine (as opposed to 23 percent in Djibouti and 86 percent in Bahrein).

The report notes that around 900 lives would be saved by early August in Lebanon thanks to the vaccine, but that the pressure on hospitals, ICU beds, and medical staff during the upcoming period remains elevated.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 20/04/2021

*References:

- Director of public relations at the Rafik Hariri University Hospital, Nisreen Al-Husseini

- The Ministry of Health website

- Interview with the director of the Knowledge to Policy Center (K2P) at the American University of Beirut, D. Fadi El-Jardali

- Reports published by the K2P Center at the AUB

- Interview with researcher Ali Mokdad at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington

- Reports published at IHME at the University of Washington

- WHO reports

1)El-Jardali F, Fadlallah R, Abou Samra C, Hilal N, Daher N, BouKarroum L, Ataya N. “K2P Rapid Response: Informing Lebanon’s Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic”, Knowledge to Policy (K2P) Center. Beirut, Lebanon, March 2020.

2)In conversation with Assafir Al-Arabi.