A mixture of latent anger, disappointment and boredom has descended on the city that, although living up to its name “Al-Qahira” (the vanquisher) has always been full of life.

Over five years, the city has changed – at least in my mind – not for the worse necessarily, as some proponents of the “good old days” like to say, but it has changed nevertheless. I can almost ascertain that it will never go back to what it once was.

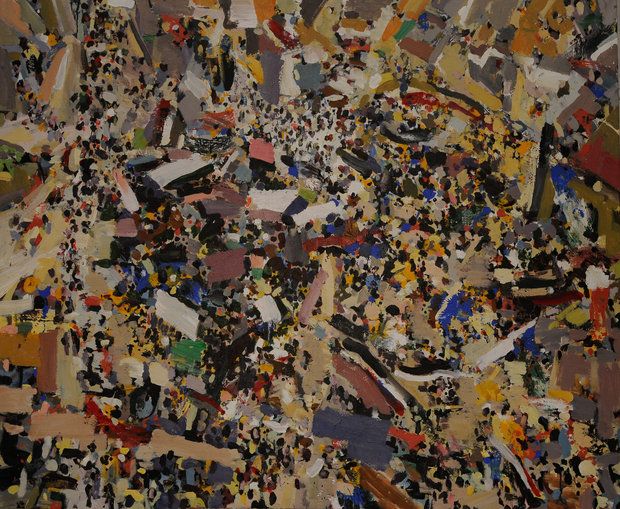

There is a compelling question for everyone – whether they are frustrated or scattered like those who supported the revolution and thought that something better is possible; or exhausted like those who followed it closely and cautiously; and even those who objected and believe it was a conspiracy and still fear the 2011 earthquake and continued aftershocks even if they are temporarily dormant.

The question is: What next? The question is on everyone’s minds, even if they do not speak it. The other compelling question, especially on the minds of a large segment of those who dreamed and believed in the 2011 revolution in Egypt: Did the revolution fail?

I don’t believe anyone, no matter who, who has an absolute answer to this question – unless they are too ignorant to realise they are ignorant. I believe there are several issues, even if incomplete, that are key to understanding what happened, and thus, more importantly, what could happen.

We must understand that what Egypt experienced over the past five years is not just political activism or even attempts at an aborted revolution, but a historical transformation of the entire society, including its political and cultural structures, and thus it will continue for decades to come.

The post-colonial state that took shape in the mid-20th century has reached the end and is no longer able in its current form to meet its multiple obligations in managing society.

Nor is it able to accommodate new generations that no longer accept exchanging freedom for economic gains which are absent anyway, or the trampling of personal dignity in a police state under the pretexts of security and national independence.

We are in the midst of a battle of redefining and questioning established concepts.

The fervour of national independence or universal conspiracy are no longer sufficient to subjugate the generations of the new millennium, especially those whose political consciousness was formed during the revolution, even if they did not participate in it.

The concepts of nation, pride and dignity have become part of public debate and are now linked to their personal lives, and are not just abstract concepts.

The verse of the famous song “Don’t ask what Egypt has given us” is no longer sufficient in responding to their questions and ambitions for a better life for the individual and the masses.

Just as an independent state was the dream of the generations of the 20th century, the dream of a free society is the aspiration of the generations of the 21st century.

Meanwhile, the welfare state that provides social advancement through education and employment – even if it is authoritarian – is over.

Amid the global capitalist crisis and ambitions of construction in Gulf states, the Egyptian state is no longer able to meet the needs of its citizens, whether through an industrial awakening like under Abdel-Nasser or Sadat’s open-door policies or even as a rentier state (exporting labour to Gulf states and relying on their remittances) under Mubarak. These economic models have diminished for global and regional reasons.

In addition, society is going through labour pains, not only in terms of relations with the state, but also in its social and cultural patterns, as well as individual relationships.

Villages and hamlets have transformed into towns, and state control of domestic media, education and cultural institutions is offset by uncontrollable openness via the internet and multiple self-education sources.

The dominance of religious institutions is offset by the rise of religious currents that may be even worse and more radical, which undermines the monopoly of religion and dominance of single institutions.

The struggle between these currents reshapes society and individuals in an unprecedented and historic manner, unseen since the end of the 19th century and the start of the 20th century with the demise of the Ottoman hegemony and the rise of Arab nationalism, the emancipation of women, and so on.

The battle goes beyond political activism, which is nothing more than a symptom of a much deeper transformation that society is undergoing.

On the other hand, the region and world are going through rapid transformations that we are not immune to, even if some believe we are.

The regional scene appears similar to events in Europe and the world in the first half of the 20th century between the world wars, the Russian revolution, the rise of fascism and Nazism, the retreat of old colonialism, the demise of the Ottoman Empire and the rise of independence movements, redrawing the borders of new countries and the start of the Cold War.

Between the swift rise of transnational powers such as ISIS and even Hezbollah as regional players, and changes in country alliances with the rise of Iran and Turkey, as well as China and Russia reaching out for an ambitious role globally especially in the region, the map and nature of regional players has changed and the game itself has changed.

It is no longer limited to calm and long-term power struggles, but rather intense and imminent explosive moments that will reshape the region even in terms of redefining the state and its borders as we knew it in the last century.

The concepts of state monopoly of justified violence and permanent regional borders, as we studied them in political science, will also be reshaped in this shift.

Consecutive global crises, beginning with the 2008 financial crisis and beyond the Greek crisis, undermine the nature of the global economic system as we know it – or at least reveals the magnitude of the crisis in the capitalist system.

In parallel, there is a rise of movements such as Occupy Wall Street, Podemos in Spain, Movimento Cinque Stelle in Italy, which indicates the demise of political parties as the main tool to manage conflicts and political competition, as well as the rise of radical right-wing rhetoric in Europe and the Arab region (albeit with different tools and motives).

These variables demonstrate the magnitude of upcoming changes in the world as a whole, including for established concepts such as the ideal political model and meaning of democracy and its administration.

Overall, we are witnessing the harbingers of the end of a domestic, regional and global epoch in history, even if it does not end tomorrow.

The starting point is to understand the nature of the stage, then ask questions about what we desire as masses and individuals for the future, and to come up with tentative plans of how to reach these goals. We must also recognise that violence by the state, like violence by transnational groups, is unstainable and unacceptable.

Accordingly, judging what has become of the Egyptian revolution or even what is known as the Arab spring as a whole is premature. We are at the start of the final chapter of a stage in development of human society, but the final scene is not yet written.

May God bless the souls of all martyrs and refugees and prisoners and everyone who takes action for the sole purpose of a better future for humankind.

*The writer teaches political science at the American University in Cairo