Warning: This investigation includes graphic images some readers may find disturbing.

On July 10, 2017, former Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi officially declared victory over the Islamic State (ISIS) in the city of Mosul, 465 kilometres northwest of Baghdad. Nine months of fierce battles since October 2016 ended when Abadi hoisted the Iraqi flag in the city and announced the defeat of the terrorist organisation that had controlled the city for three years, its stronghold in Iraq. From Mosul’s Great Mosque of al-Nuri, ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi had declared the city the capital of the ISIS “caliphate”.

The war was over in Mosul, but other battles were still unfolding. The returnees to the old Iraqi city are still dealing with poverty and disease, and with unidentified bodies buried under the rubble of demolished and mined buildings. Their recovery has become a daily occurrence, no longer newsworthy.

Entering the old city

We enter the city through its west side, the Right Bank of the Tigris, and head to the al-Shahwan neighbourhood. A destroyed house with a crumbling roof and walls catches our attention; we suspect there is a story behind it. We are right. Local residents greet us and tell us what happened.

Muhammed, 33, witnessed the moment the house was hit with two missiles during the battle to recapture the city.

“The owner of this house was a senior ISIS leader in Mosul. During the organisation’s control of the city, the house turned into a Diwan of Zakat [a religious taxation department]. During the military operations for the liberation of Mosul, several ISIS families arrived and were based in that house. Almost a week later, the house was bombed with all the women and children in it,” he tells us.

“The house contained oil barrels and an underground basement. It was bombed around 3am. We heard the screaming of the children and women who were set on fire. They kept screaming for two hours, until 5am. Then there was silence.”

Muhammed points at the house. “The injured were taken by ISIS militants, but the dead still lie under the rubble. Dozens of bodies remain buried under the wreckage and still have not been recovered.”

Khaled Ezzat, 58, also saw the bombing and tells us about a woman who survived. As we talk, neighbourhood children throw rubbish bags into the burned-out property.

“She told us that all their money was inside the house and that there were 64 people living there, 14 of whom were evacuated. Some were wounded, and others were dead. The remaining 50 people are still under the rubble.”

We enter the house and wander around with great caution, having been warned that explosive devices might still be there. We see human bones among the rubble, and the remnants of an explosive belt.

Neighbourhood residents, without exception, speak of the heavy psychological toll on their mental and physical health due to the unrecovered bodies under the rubble. The house has become health hazard, a breeding ground for stray dogs and a den for snakes, scorpions and insects.

The stench of death

Al-Shahwan witnessed devastating battles between the Iraqi ground forces, supported by air strikes, and ISIS, which fought fiercely to keep the city under its control. It is among the most devastated areas in Mosul. According to the mayor, Zuhair al-Araji, 80% of the Old City (the western part of Mosul) was wrecked and 15 of the city’s 54 residential neighbourhoods were razed to the ground, including al-Shahwan. Half of the buildings in 23 neighbourhoods were completely demolished, and 16 neighbourhoods were only “slightly” damaged.

Al-Shahwan feels like a Second World War movie set. The destruction is terrifying, with torched cars piled up on tons of rubble, wreckage from destroyed houses, and skeletal human remains.

Umm Muhammad, 64, is one of the few residents who returned after the battle to liberate Mosul. When we arrive at her house, she is sitting on her doorstep, as she often does. Holding a long white rosary in her hands, she counts the losses of Mosul’s inhabitants, reminiscing about the old times and remembering her neighbours. Some have been killed, others were displaced and have never come back.

“We were living in paradise. The earth of my neighbourhood means the world to me,” Umm Muhammad says as she looks at the devastation around her. Her house is one of the few that has been restored.

“When the battles were over, we returned home, only to find it destroyed. But the benevolent people donated money to me to have it restored,” she says as she moves the beads between her fingers. “But the stench is killing us. The stench of death. And the insects, scorpions and snakes have proliferated because of the mounds of corpses here.”

She takes us on a tour through the rubble of the neighbourhood. We pass through alleys, and on collapsing walls find the words “There is a family here” written, with an arrow pointing the way.

In another house, we find human remains covered with blankets, pieces of cloth, clothes and shoes. We also find explosive belts.

It is dangerous to enter these houses; mines and unexploded bombs are scattered around, as are explosive belts on the bodies of fighters who died before having the chance to blow themselves up.

The booby-trapped city

The United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) estimates that thousands of tons of explosives are still scattered throughout Mosul, saying in April 2019 that it may take over 10 years to completely clear the city. According to Paul Heslop, Director of Programmes at UNMAS, before the onset of the military operation to liberate Mosul, ISIS fighters had two full years to plant explosives and bombs.

“Many buildings had collapsed on people. Many others had been booby-trapped to prevent people from returning to their homes. This is not to mention the unexploded ordnance and explosive remnants from the actual fighting,” Heslop says. “Every single object could be a potential danger. The fridge could be booby-trapped and would detonate once you opened it. Things would blow up if you switched on the light. Buildings are also crumbling, and it would only take one wrong move on the part of the search teams for unexploded ordnance and mines to blow up, causing the entire building to collapse over their heads.”

We wander further into the devastation with Umm Muhammad. Human thigh or arm bones protrude from the rubble. “We sleep with corpses,” she says, but is adamant that she will not abandon her house, after a bitter displacement and war experience. “This is the land of my father and grandfather. Where else would I go? We only ask the government to compensate us for the destruction of our homes and the killing of our children.”

Her eyes flicker. “See that hill over there? Well, it’s not exactly a hill. These are houses that were razed to the ground, with everyone inside them killed and buried under the wreckage. Here in the al-Biah area, we are dying of the stench of corpses. The walls of houses could collapse any moment on children. A few days back, a child fell into a basement of a destroyed house.”

Umm Muhammad speaks of her husband, who died of cancer, and of her sons, whom ISIS militants threatened to kill because they worked with the police. They fled Mosul and never came back. She also tells us about her struggles after the international sanctions on Iraq began in 1990. Back then, she used to sell bread and vegetables on the pavement across from her house. Then came the hardships of the occupation and liberation of Mosul that resulted in the devastation surrounding her house today. She has had to rely on donations to survive.

“Can you believe that this land was once home to innocent people?” Umm Muhammad says as she points at the barren land surrounding her home and leading up to the banks of the Tigris River, which cuts the city in two. She keeps walking as she recalls the names of her neighbours and the locations of their homes, completely wiped out by the war.

“This was the house of Canaan. He was killed in the battles. This was the house of my aunt’s husband. She lies under the rubble. Her body has yet to be retrieved. Over here was the house of Hajj Shukhir, there the home of my cousin Waad. All these houses were razed to the ground. This was the house of my husband’s uncle, who had two sons who were killed too. One was a paramedic who died in one of the battles as he was helping his injured friend. He got a bullet in the chest. Here was Khoudouri’s house, there was Riyadh’s, a good friend,” she says with a heavy heart, choking back tears.

We come across a crater in the ground which leads to a basement in the house of an ISIS militant named Hussein, according to Umm Muhammad. ISIS used the basement for military purposes.

“Look over here, this is not a barren land. These are houses that were levelled to the ground and their owners buried underneath,” she says as tears trickle down her cheeks. “The decent young people are gone. The decent people are killed. The neighbourhood is dead. We used to live in harmony, helping each other out. When my husband died, the mourning reception lasted for seven days and all the neighbourhood’s residents were there for me. People here were nice and kind. They are all gone now. Those who didn’t die have been displaced and have not returned.”

Recovering the bodies

When the battle to liberate Mosul came to an end, the death toll was 3,176, of whom 1,429 were civilians, according to Iraqi War Media Department figures. However, the lists of identified and unidentified bodies still being recovered from the Old City indicate that there were far more than 3,000 victims.

According to the Associated Press “The price Mosul’s residents paid in blood to see their city freed was 9,000 to 11,000 dead, a civilian casualty rate nearly 10 times higher than what has been previously reported. The number killed in the nine-month battle to liberate the city from the Islamic State group marauders has not been acknowledged by the U.S.-led coalition, the Iraqi government or the self-styled caliphate.

We meet Brigadier General Hussam Khalil, Director of Civil Defence in Nineveh. He shows us the number of recovered bodies in Mosul that are in the possession of the Civil Defence Directorate.

“The Civil Defence has recovered 2,600 bodies that were identified of innocent people who perished in the battle to retake Mosul. Some 750 corpses belonged to women, and 850 to children who could not exit the city. There are also some 2,200 unidentified bodies belonging to ISIS militants. This brings the total of recovered bodies in the city of Mosul to 4,800,” he tells us.

These numbers are higher than those of the War Media Department and of the Iraqi High Commission for Human Rights (IHCHR), a government institution affiliated with the Iraqi parliament. In December 2018, IHCHR announced that the total number of bodies recovered from the city of Mosul was 4,720, including both identified and unidentified bodies.

Khalil says the Civil Defence has completed about 98% of the work of recovering the bodies scattered all over the city, explaining that this depends mostly on calls and reports from citizens or service departments in charge of removing rubble and carrying out service projects.

“The process to retrieve dead bodies is a delicate and difficult one, given the nature of the area where the Civil Defence teams work. The city’s streets and alleys are narrow and destroyed, making it difficult to bring in heavy equipment necessary for the search for bodies in the rubble. This is not to mention the war remnants that lie with the bodies under the rubble, such as explosive belts and weapons belonging to ISIS militants. What makes matters worse is the lack of tools and equipment needed to retrieve bodies. After the liberation of Mosul, the Civil Defence did not possess any machines or equipment.”

Other figures

In the wake of the liberation of Mosul, the Body Recovery Committee was formed, headed by Duraid Hazem, an engineer. According to Hazem, from the end of the battle through the end of 2019, the recovered corpses numbered 5,524, of which 2,872 were unidentified and 2,652 identified. He confirms to us that work to retrieve bodies is still ongoing.

“As long as there is rubble and destroyed houses in the city of Mosul, this means that more bodies lie beneath them. The area between the Shaareen market and the Fifth Bridge in the Old City was the last battlefield between the Iraqi forces and ISIS. The fighting was fierce, assisted by air strikes. It is one of the most destroyed areas in the city and the bodies remain under the rubble,” he explains.

He adds that the state does not possess the means to remove the huge quantities of rubble and debris in the city. “We as a committee worked in cooperation with the Mosul municipality, the Civil Defence and the Forensic Medicine Department. But because of the lack of adequate equipment, we could not get to the bodies deeply buried under the mounds of rubble.”

Qlaiaat, one of the city’s oldest neighbourhoods, was home to the Assyrians after the fall of their empire in 612 BC at the hands of the Medes and Chaldeans. This archaeological area witnessed the last battle between the Iraqi army and police and ISIS, known among citizens as the “final battle”. The remaining ISIS fighters and their families, as well as other residents who could not escape, were trapped and besieged. ISIS used people as human shields.

Qlaiaat has been reduced to rubble by intensive Iraqi army shelling and air strikes by the international coalition forces supporting Iraq in its war on ISIS, not to mention the mines and bombs planted by ISIS in homes and streets. The Civil Defence recovered some 500 bodies, mostly those of women and children, from the archeological area alone. The suspension of the search for bodies turned Qlaiaat into a mass grave for hundreds or perhaps thousands of people. They remain buried there, with no way for the Civil Defence teams or the municipality to recover them, due to the colossal devastation.

Nawfal al-Aqoub, a former Governor of Nineveh who was sacked over charges of corruption and mismanagement, gave the order to bulldoze the area to make it available for property investors. Heavy steamrollers and bulldozers rolled over the remains of the dead and the rich history of the city.

We head to Erbil, where Aqoub lives, and try to meet with him to ask him about this decision. He turns us down and then stops taking our calls.

Hazem, however, explains to us that the decision to bulldoze came from the local government in Nineveh, in a bid to bring the area back to life and open roads. “A Street cuts into the old town on the banks of the Tigris River. Because of all the destruction, the features of the street were no longer clear. This was why the local authorities decided to clear the way and bulldoze the area.”

Commenting on who was responsible for this decision, Hazem says, “The city is old, with rundown buildings and narrow alleys, some of which are only two or three metres wide at most. In order to enter the area, the bulldozers had to knock it down.”

We also speak to Hazem about the people’s complaints and suffering because of the scattered corpses, bones and body parts in residential neighbourhoods. He downplays the magnitude.

“There are no bodies per se, but rather skeletons and body parts. The corpses decompose over time. I think the residents are exaggerating their effect a bit. Recovering the remaining bodies is extremely difficult. The Old City was 95% destroyed. Removing the rubble to retrieve the bodies is not as simple and evident as people claim.”

After leaving Hazem’s office, we wander for some time in the streets of the Old City and talk to random people. Omar Muhammad, 35, lives in the area.

“The Old City is full of corpses. The stench of death is horrible. This is not to mention the diseases. It is the duty of the Civil Defence to retrieve these bodies. Areas such as al-Makawi, al-Hadira, Ras al-Kour, al-Maydan and Qlaiaat are full of corpses covered with blankets, reeking of horrible smells,” he says.

Samed Saleh, 43, tells us, “I used to live in the Old City. I want to come back, but how? Dead bodies are scattered everywhere in the city. It reeks and is plagued with disease. The authorities have recovered a few dozen bodies, while the city sits on a bed of corpses. This is a crime. The government needs to act quickly so people can return to their homes.”

Asked if the process of retrieving bodies has been completed, as the Director of Civil Defence has stated, he says, “This is not true. I was just in one of the nearby areas, and the stench would make you gag.”

Are there 27,000 bodies under the Mosul rubble?

There is great secrecy about the number of victims of the battle of Mosul, from the federal government and its institutions in Baghdad, and from the local government and its departments in the Nineveh Governorate. We have been unable to obtain accurate figures for the numbers of dead, wounded or missing. No databases are kept in any of the government departments concerned with this issue.

The government’s War Media Department, however, is very open about the number of ISIS deaths. According to Iraqi security forces figures, 30,000 ISIS militants were killed in the nine-month battle.

If we do a simple mathematical calculation based on the official Iraqi figures, whether the Baghdad central government or the Nineveh Governorate, we have the following:

According to Hazem’s figures, there are 5,524 recovered bodies, including 2,872 bodies belonging to ISIS. If we deduct the 2,872 from the total of 30,000 dead ISIS militants killed by the Iraqi forces (according to their media department), we are left with 27,128 bodies still under the rubble in the city of Mosul.

On July 19, 2017, the Independent newspaper obtained an intelligence report from a top Kurdish official in Iraq’s Kurdistan region. The report includes over 40,000 undeclared civilian casualties in the battle of Mosul, far more than the official figures declared by the Iraqi government. It also contains an exclusive interview with Kurdish leader Hoshyar Zebari, formerly the Iraqi Minister of Foreign Affairs and then Minister of Finance, who confirms the figures.

“Kurdish intelligence believes that over 40,000 civilians have been killed as a result of massive firepower used against them, especially by the federal police, air strikes and ISIS itself,” Zebari, who comes from Mosul, says in the report. “The unrelenting artillery bombardment by units of the Iraqi federal police, in practice a heavily armed military unit, caused immense destruction and loss of life in west Mosul.”

Stories of the missing

In addition to the massive destruction in Mosul and the bodies all over the city, the issue of missing people remains a thorny one. According to the (dissolved) Nineveh Provincial Council, 5,000 people were reported missing following the battle to retake the city from ISIS.

What makes matters worse is the fact that the local government does not have a database of the names of the missing individuals, whose fate remains a mystery. It remains unknown whether they were kidnapped or forcibly disappeared by ISIS, or taken by the Popular Mobilisation Units (PMU) that partook in the battles, or detained by the Iraqi security forces. They could also be among the bodies that lie beneath the rubble.

The second time we visit Umm Muhammad in al-Shahwan, she tells us about a neighbour. She points at flat land that looks like totally uncharted territory. “Riyad – Abu Ubayda al-Wared – was like no one I knew in Mosul. A decent man. He was abducted by ISIS militants during the battle because he worked for the police. His fate remains unknown.”

This leads us to Riyad’s family, displaced from the al-Shahwan neighbourhood since the battle to liberate the city. They now live in a small rented house in east Mosul. Their hopes of seeing Riyad again are growing smaller as his children grow older, waiting to find their father, alive or dead.

Obeida Riyad, 25, the eldest son, often sorts through pictures of his father taken with his friends and his children. He recalls when Riyad was kidnapped by ISIS. “My father, Riyad Fawzi, was kidnapped by ISIS guerillas on 12 April, 2017 at eight in the evening. He was impatiently waiting for Mosul to be liberated so he could join the security forces,” Obeida says.

“A group of ISIS militants showed up at our house and asked me where my father was. I said he wasn’t home. They still stormed in and knew that my father was hiding there. They told him they knew he was affiliated with the police. They asked him to atone. They pressured him to hand over his SIM card and they searched the house for it. When they did not find anything, they told him they were taking him with them for investigation. He never returned home. We still know nothing about what happened to him. My father was loved in the area where we used to live. Ask anyone about Riyad, the policeman driving a white Corolla, they would say he was a decent man.”

© Qassem Al-Zaidi/Candid Foundation

The family know nothing of Riyad’s fate. However, Obeida mentions rumours of ISIS abductees being liberated by the security forces and taken to the Muthanna airport in Baghdad, or to al-Hout prison in the city of Nasiriyah, in the country’s south. Some claim that they remain detained in ISIS basements. Riyad’s family still entertain the hope that he is among those who survived.

The family of five live in dire conditions. Obeida had to drop out of school and work in construction, in order to look after his siblings and mother. He complains about the difficult economic situation in Mosul and the stagnation gripping the city emerging from war. He gets paid 30,000 Iraqi dinars ($25) a week. And they lost everything during the battle.

“My father was kidnapped by ISIS. Our house was completely destroyed and it does not exist anymore. We lost our car too. We left al-Shahwan neighbourhood with nothing but the clothes we had on. But everything will be fine as long as my father shows up, or we at least know his fate,” Obeida says.

Unfortunately, the young man did not emerge from the war unscathed. “I got hit by shrapnel during the shelling. I injured my stomach and feet. When I walk, I feel my feet are so heavy, pulling me down.”

Ahmed, 12, is Riyad’s youngest son, only eight when his father was abducted. He remembers and misses his father. “He used to drive me to theme parks and to Mosul’s tourist forests. He used to buy me everything I wanted. I miss him mostly when I see other fathers dropping their kids off to school and I am there all by myself. If he were still here with us, he would give me pocket money every day. I don’t ask my oldest brother Obeida for anything because I know he does not have money. I don’t want him to feel sad because he can’t provide me with money.”

When Mosul was liberated, Riyad’s family tried to return to their neighbourhood to search for him among the bodies that filled the Old City.

“The security forces did not allow us inside the al-Shahwan neighbourhood until six months after its liberation. Corpses were everywhere, mutilated. It was difficult to find anything that belonged to my father,” Obeida tells us.

Bodies litter Mosul’s streets

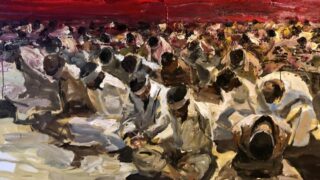

In 2017, Sorour al-Husseini was leading a team of six people whose mission was to search for corpses and pull them out of the rubble. This volunteer team was made up of civilian activists who took it upon themselves and risked their lives to rid the city of its veil of death.

“In November 2017, we visited the Old City of Mosul and were shocked to see mounds of bodies littering the city’s streets. We immediately went to the municipality and the Ministry of Health and the Civil Defence to obtain the necessary official permits to start pulling out bodies. It took two months for approval. We began work in January 2018,” Husseini tells us.

She explains that her team was driven by fear for the city and its citizens. “When we saw thousands of bodies in the streets and under the rubble, we thought that an inevitable epidemic would plague the area, and that those who had not died because of ISIS would perish from a serious disease. Also, people had to eventually return to their homes sooner or later. They couldn’t do this with bodies scattered everywhere.”

Husseini tells us that she and her team recovered over a thousand bodies. She shows us video footage of the team pulling out corpses in the Old City. Many of the retrieved bodies were missing parts – a hand, a leg, a head. She explains that this made it difficult for them to fill in the forms describing the bodies.

“Our work was limited to pulling out corpses, not burying them. We worked at the beginning with the municipality of Mosul, and then we cooperated with the municipal and forensic departments. We collected bodies from under the rubble, basements, streets and any place we could reach the corpses. We did not have any equipment. We used to place the bodies in special bags and seal them. We took the bags out of the heavily destroyed areas to streets with less destruction where vehicles could drive. The municipal department would collect the bodies and take care of the burial procedures.”

She elaborates on the procedure. “The three oldest people on the team, i.e. my husband and I and our friend Muhannad, used to enter the houses that had corpses inside. Usually, we would detect the bad smell or the inhabitants of the areas would help us to locate bodies, as well as soldiers from the 7th division of the Iraqi army. Sometimes we would be assisted by soldiers from the Nineveh Operations Command. But we used to be accompanied by the intelligence apparatus at all times.”

“The three of us, the oldest ones, would enter the premises first to make sure no explosives were in our way, because our major challenge was the booby-trapped bodies. When we spotted one of those, we did not let the younger team members get near. When the path was clear, we communicated with the rest of the team through walkie-talkies. They would come to our spot with bags to be filled with corpses. The bags would be sealed and placed on the street for the municipal vehicles to collect.”

Husseini also found herself embroiled in a judicial battle with the Governor of Nineveh at the time, Nawfal al-Aqoub, over the unretrieved bodies in the city – he denied their existence. She tells us about the first time she met him.

“During one of our missions in the field, we were retrieving bodies and a German DW TV crew accompanied us the whole day. I then got a call from Ali Jaafar [host of the Shabab Tok show on the DW Arabic channel], who wanted to feature me on an episode. I agreed. I went on set and before filming the episode, Jaafar introduced the other guests, including Nawfal al-Aqoub. When Jaafar introduced me and talked about my team’s work, Aqoub got really worked up and upset, accusing me of being a liar, denying the very existence of corpses in Mosul.”

After this verbal altercation on the show, Husseini was summoned by the Nineveh Operations Command (the largest military formation of the Iraqi army in the Nineveh Governorate) for investigation.

“After the investigation, we were acquitted by the Commander of the Nineveh Operations Command, Major General Najm al-Jubouri, after he found out about our volunteer work and the support we offered to the municipality of Mosul and the forensics department in the recovery of bodies.”

Husseini was surprised to learn that Aqoub had filed a case against her before the Mosul Investigation Court. “My trial was postponed several times. I was referred to the Misdemeanour Court and was released on bail of 5 million Iraqi dinars [$4,200],” she says.

“A year after the litigation, I was a guest at an exhibition on the sidelines of the Erbil Book Fair, to talk about my experience in retrieving bodies. One of the journalists asked me about the lawsuit filed against me by Aqoub. This was the start of a campaign by journalists and professional media workers, who signed a petition to have the charges dropped against me. It soon turned into a public opinion issue. When I appeared in court, the judge dropped the charges for lack of evidence.”

Hussieni gives us copies of the court’s ruling acquitting her, and tells us that her team of six people expanded to 40 volunteers from among the young men and women of Mosul.

She confirms that the neighbourhood of Qlaiaat and al-Maydan contained the most bodies. “The Qlaiaat neighbourhood was completely destroyed, as it was the last stronghold of ISIS, where the final battle took place. The area was heavily bombarded with fierce battles on the ground, which resulted in colossal human casualties.”

She also confirms that heaps of corpses remain. “A month ago we visited the west side of the city. Human bones and body parts littered the streets. I don’t have an exact figure of the remaining bodies, but I know for sure that they are in great quantities. We do not have the necessary tools or means to be able to detect the exact numbers.”

Yet another battle: 40,000 stray dogs

The hardships of the people of Mosul are compounded by yet another battle. The city has some 40,000 stray dogs, according to Dr Uday Shihab al-Abadi, Director of the Veterinary Hospital in Mosul. They roam the streets in the east and west sides of the city, spreading fear and disease.

Abadi says a thousand dog bites are reported each month. The first campaign against stray dogs was launched at the end of 2019, two years after the city was retaken, during which time the dogs had been feeding on dead bodies. He explains that the local authorities poison dogs through food, which he sees as a peaceful way of dealing with the issue without affecting the community.

In accordance with the Iraqi Law of Combating Stray Dogs no. 48 of 1986, stray dogs on public roads, outside homes in the cities, and in rural areas can be killed by sniping or any other method. The law adds that the Minister of Agriculture may issue instructions to this effect according to the propositions of the competent departments. The second article of the law stipulates that the competent authorities shall collect the perished animals to be torched in remote areas designated for this purpose.

Stray dogs roam public parks, streets, ruined buildings and mounds of rubble. They attack passers-by and enter homes, spreading disease and causing injuries that are sometimes fatal. Mosul’s dogs constitute yet another epidemic in the war-battered, corpse-filled city.

This investigation was carried out with the support of the Candid Foundation.

Read in arabic at Assafir al Arabi: https://cutt.ly/5bM2f0e